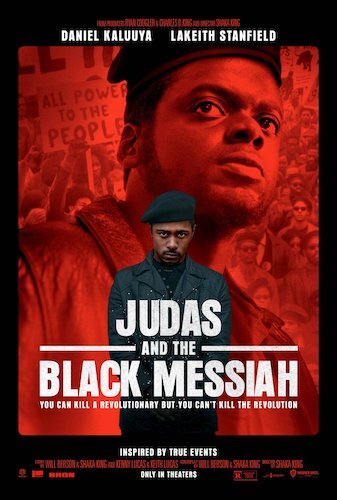

Judas and the Black Messiah

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Every awards season has a last-minute participant, and each year has varying results with how this particular film (or films) changes the landscape of these few months. In 2021, things are already a little strange. Minari and Nomadland are finally available for the masses, but Judas and the Black Messiah still feels like the late game changer, because it wasn’t a 2020 film festival release (if anything, it was released at the Sundance of 2021). While the film was meant to be released in August of last year originally, it still seems like the readjustments of the film’s release were always going to be after other films made a big splash. It was clear that Shaka King and Warner Bros. Pictures were going to be playing the late game already, but now the film is smack dab in the middle of the delayed releases of other works. Still, it has a couple of award nominations ranked up (mainly for Daniel Kaluuya), but I have a feeling this could affect the Academy Awards, where things really count (kind of).

Part of this shake-up is timing, but the majority is quality. King’s second film (after 2013’s Newlyweeds) is a sensational effort that is fitting for a world that’s still feeling the remnants of the political climate of 2020, whilst depicting the divide of America in the ‘60s and ‘70s at the same time (mainly because injustice has continued for centuries, so the film can speak for both eras). Judas and the Black Messiah is centred around informant William O’Neal and his involvement with the assassination of chairman of the Illinois Black Panther chapter Fred Hampton. It’s clear right away that the film isn’t meant to vilify O’Neal, but prove that his choices were enforced by his own difficulties in society. O’Neal notices that agent Roy Mitchell is living comfortably: something he has never experienced. Mitchell is willing to grant O’Neal his wish of having a better life, but at the price of extreme betrayal. Otherwise, the crimes O’Neal committed to survive will haunt him for the rest of his life.

O’Neal and Mitchell working together, much to the chagrin of the former.

Not once do you feel like O’Neal is getting greedy, even if he starts dressing better. If anything, his purpose for abiding by the FBI’s requests (to help bring down the Illinois Black Panther chapter from the inside) shifts throughout the film; the primary reason towards the end is to save himself. Whilst infiltrating the Black Panther party, O’Neal finds himself in complete support of what Hampton and his contemporaries are trying to fight for; this film felt reminiscent of the informant storyline of Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman, but strung out for two hours, and with far more complexity for this particular plot thread. So much of the film is dedicated to O’Neal being torn between what is right for society, and right for himself to live. It’s saddening to know that O’Neal would lose to his personal demons and regrets in 1990, committing suicide after the release of the documentary Eyes on the Prize II (which he partook in).

This internal battle is exemplified by an always-fantastic Lakeith Stanfield, who I have said time and time again is one of our generation’s finest actors (and his lack of major accolades is frankly unforgivable). Stanfield bounces around between his real guilts and his put-on persona (which merges into his actual ideologies). You can sense his anxieties and overwhelming stress at all times. Of course, the real scene stealer — as everyone and their dog has brought up by now — is Daniel Kaluuya as Fred Hampton, who pinpoints the late activist’s voice and mannerisms with frightening accuracy. Then, Kaluuya passes the great test of many thespians: can they replicate the speeches of the icons being portrayed as well as the icons themselves? The answer is a clear yes, as Kaluuya is virtually impossible to ignore when he’s playing Hampton at the podium, commanding listeners to hear his words. I’ve previously brought up Leslie Odom Jr.’s borderline lock for Best Supporting Actor with One Night in Miami: Daniel Kaluuya has now given him some fierce competition.

Daniel Kaluuya has delivered his finest performance yet as the late Fred Hampton.

Judas and the Black Messiah could have been an acting vehicle that gets by on its dynamic performances, but King and company vowed to make this film truly something. They succeeded, with a slow burning buildup of tension. O’Neal’s double life has lies piling up. Hampton’s activism leads to the lack of his own safety, either by the opposed members of the general public, or by authorities. Then, there’s King’s fantastic use of circling motifs, including O’Neal’s tactics for grand-theft-auto (his artificial police badge makes several clever reappearances). These motifs act like O’Neal’s nightmares coming back to curse him, either as a reminder that a person of colour doesn’t get a fair shake in society, or that his cooperation with the FBI is wrong.

When O’Neal begins to crack under the pressure, Judas and the Black Messiah may have used this opportunity to just focus on this character’s psyche, but King uses it as an opportunity to better detail the corruption of the law, and Hampton’s ideologies being laid out better (an example of the latter is when Hampton doesn’t approve of O’Neal wanting to commit an act of terror, which was actually O’Neal’s way of trying to get out of his position out of desperation but could have been seen as a way to try and benefit the Black Panther party with extreme violence). It’s this devotion to laying out every small detail as precisely as possible that makes Judas and the Black Messiah more than just a biopic; it’s honestly a political thriller at times, with history used as inspiration.

The personal demons of William “Bill” O’Neal dominate the picture.

It’s easy to say that 2021 is off to a good start, if you’re looking at major films that were delayed from last year. If I was to not include films I saw last year meant to be released last year as 2021 releases (so any 2021 release that wasn’t on my 2020 list), then Judas and the Black Messiah is currently the finest film of the year. There’s so much ambition and intensity here that is impossible to ignore this awards season; then you remind yourself that it’s strictly a fantastic film through and through. If the Academy were to turn a blind eye to Judas and the Black Messiah (especially during a less-than-stellar awards season), then it would be an extreme travesty. A Best Supporting Actor nod for Daniel Kaluuya is not enough (although that has to happen). This film deserves a ton of the big tier nominations, and even some fundamentals if there’s room (it is well edited, for instance). I’m also talking about Best Picture, which Judas and the Black Messiah more than deserves a nomination for (Shaka King being a late entry for Best Director isn’t such a bad idea, either).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.