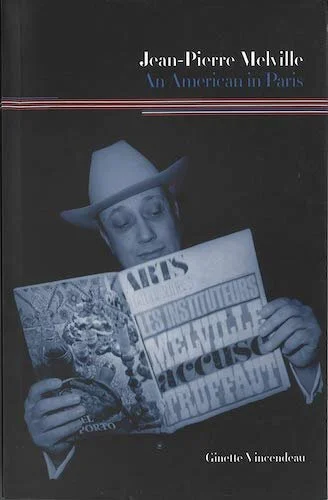

Film Book Review: Jean-Pierre Melville: An American in Paris

Written by Cameron Geiser

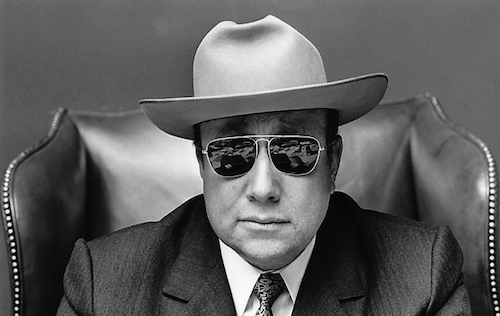

If you're new to Jean-Pierre Melville's work, you'll need a few things to settle in for the journey. First and foremost, a black or beige fedora and a simple raincoat — always buttoned and tied at the sash regardless of rain or shine. Next, you must have a pack of cigarettes and a gun, preferably a pistol, but a submachine gun will do in a pinch. Though, that's a bit much for our minimalist French director's taste. Lastly, practice your best aloof, cold, and calculating stare. This will complete your style and mindset for a Melville film; welcome. Jean-Pierre Melville: An American in Paris by Ginette Vincendeau, who was a professor of film studies at the University of Warwick, England (now mostly a film critic), is an academic analysis and breakdown of the French Resistance filmmaker's work as one of the pioneering film directors of the French New Wave and beyond.

While Vincendeau does attempt to give us a picture of the man behind the camera in the first chapter, she notes that Melville was notoriously vague and intentionally created mystery surrounding his actual day to day life. This is, after all, an analysis of the films rather than the man himself. There were, of course, some facts that could be pinned down through research. Born Jean-Pierre Grumbach in 1917, he didn't take the moniker Melville until his time as a resistance fighter during the second world war, which he took from one of his favorite American authors: Herman Melville. He was even evacuated from Belgium by way of the events of Dunkirk! Later in the war, his time in London was hazy, with details being hard to track down at this point, but Vincendeau could point to his time in Spain being jailed for two months around November of 1942. Then North Africa, where he joined the Free French Forces in Tunisia in autumn of 1943 and later during his wartime journey through Italy as well. Vincendeau takes the time to ground the reader associated with Melville's wartime experiences, since they influenced much of his artistry throughout his filmmaking career. In fact, the book is grouped together by categories of films, which is mostly linear through Melville's career, though not entirely. They are as follows; Stylistic Exercises, Melville's War, Between the New Wave and America, Serie Noire or Film Noirs, and the Delon Trilogy.

Each chapter attempts to give context to the films through recorded interviews Melville participated in, or identifiable facts about where the filmmaker was in his life at that time. For example, in the “Stylistic Exercises” chapter, Vincendeau points to Melville's choice of screenplays, adaptations, and collaborators who could give Melville the credit and acceptance he would need from the French film critics and the commercial industry of filmmakers to be able to finance his work and be considered an artist —not just an aspiring amateur or even, (gasp) a dilettante! Both Les enfants terribles (The strange ones) and Quand tu liras cette lettre (When you read this letter) contribute in this way to Melville's effective strategy in the beginning of his career. Les enfants terribles, his second feature, is an adaption of a popular novel by French author Jean Cocteau, who also wrote the screenplay. Though Quand tu liras cette lettre in particular was Melville's most dispassionate film. He even said as much himself at the time, for he was trying to prove that he could craft a film just as good as any French director of the time without overindulging in style over substance. While I haven't seen all of Melville's films yet, these two were, personally, the hardest to get through- a common notion even among Melville's most ardent fans. His first feature film however, Le Silence de la Mer (The Silence of the Sea), was quite good and an impressive freshman film from that era in my opinion.

Melville's war films chiefly consist of Le Silence de la Mer, Léon Morin, prêtre (Léon Morin, Priest), and L'armée des ombres (Army of Shadows). Though, I suppose I should refrain from calling them “war” films, as they do not indicate the same type of film that most audiences would expect from such a categorization. All three films are adaptations of books, some a bit more biographical, others more fictional in nature. My favorite of the three is actually Melville's first film, which has a unique hook for its story. It’s a small film, set in Paris during the occupation, in which SS Nazi officer Werner von Ebrennac (Howard Vernon) is housed in a local Parisian house with an older Frenchman simply named, Uncle (Jean-Marie Robain), and his young niece (Nicole Stéphane). Upon the Nazi's arrival, both L'oncle and La nièce agree to live as though he had never arrived: with a vow of silence between them, which is only interesting because of how it affects Werner von Ebrennac over the course of the film. He considers himself an intellectual, he's well read, a lover of Paris and the arts, and a firm believer in Germany's cause — until he finds evidence of the cruelty being committed against the Jews, and it breaks something inside of him. It's a unique film regarding the Nazi occupation of Paris, and I highly recommend giving it a watch. I would also recommend Army of Shadows, though it is from the later period of Melville's career where patience regarding scene and shot length will be required.

Further context is given in each chapter based on the critical response to each of his films and how well each did at the French box office. Ironically, Melville's most divided film in terms of the critical response is his most well known and beloved film, Le Samouraï. I really appreciated the research put into showcasing how Melville's films were critically and financially received. There's a good portion of the book that constantly references the love affair and subsequent feud with influential French Film Magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, of whom both Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut would emerge from as artistic pillars of the French New Wave film community. After becoming more commercially successful through his noir films Le Doulos (The Informant) and Le Deuxième Souffle (Second Breath), Cahiers du Cinéma severed the cozy relationship with Melville by accusation, essentially, of “selling out”. Which, personally, I think is an unfair critical response- but hey, it was what it was.

In fact, it was mostly his later films that drew me to Melville in the first place. My first Melville film was Bob le flambeur (Bob the Gambler), and I can think of no greater introduction to his films, Bob has historical significance in how it was shot on location and how it's influence helped to fertilize the ground for the burgeoning New Wave films and filmmakers just a few years later. It also heavily influenced the later film Ocean's Eleven through it's heist portion of the story. Though, truly, the most enthralling and exciting films from Melville are his Noirs like Le Doulos and Le Deuxième Souffle; or his wildly popular Policiers; Le Samouraï (The Samurai), Le Cercle Rouge (The Red Circle), and Un flic (A Cop). These three consist of what is commonly referred to as 'the Delon trilogy' as each film starred popular French film actor Alain Delon in prominent roles.

His later films, particularly from Le Doulos onward, have increasingly blended a nostalgia, and aesthetic appropriations of elements of classical Hollywood crime films from the 1930’s and 1940’s, with the melancholy and abstract construction of postmodernism in how the characters act and perform within the stories at hand. All of Melville's gangster films are about the futility of action, tragic characters that are (mostly) all doomed from the outset, and nearly all of the male lead characters become increasingly detached from the human aspects of life. Le Samouraï, in particular, focuses on a gangster without a gang, as Vincendeau pointedly notes during her analysis. Alain Delon's Jef Costello is a hitman working within the confines of the Parisian underworld, sure, but he is so singular and statue-like throughout the film that his performance imbues the atmosphere with an otherworldly nature that adds yet another layer of separation between Melville's curated minimalist dreamscape of violence, loyalty, and betrayal- and the real world.

While this book was more academic in nature than I had initially anticipated, it is incredibly well sourced with notes and annotations all over the place. If you're looking for information regarding Jean-Pierre Melville, specifically a wide-ranging analysis of his films, I doubt you could find a better source. However, I must give a bit of a warning in that the treatment of women characters in some of his films aren't the most progressive to say the least; indeed, there are large portions of the book that dive into gender analysis of the characters, their roles within the films, and the films as a whole themselves, if that interests you. Jean-Pierre Melville was one of the most prominent and influential independent post-war French filmmakers, and if you have any interest in international film, he's one to look into!

Cameron Geiser is an avid consumer of films and books about filmmakers. He'll watch any film at least once, and can usually be spotted at the annual Traverse City Film Festival in Northern Michigan. He also writes about film over at www.spacecortezwrites.com.