Annihilation: On-This-Day Thursday

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For February 23rd, we are going to have a look at Annihilation.

This review contains major spoilers.

Usually for my On-This-Day Thursday write ups, I like to travel a little bit further back in time than three measly years ago. There’s an explanation for why I am writing about Alex Garland’s Annihilation today, and I hope this review will be enough persuasion. In short, it’s a bit presumptuous to proclaim a film I subjectively love as an instant classic, but I feel that this thriller truly is one of the finest science fiction works of the twenty first century; with that type of competition, wouldn’t it only make sense that I feel comfortable in my labeling of this film? I can only feel this way about a film if I believe it will be one of those works that ages better with time, since my certainty right now isn’t exactly the overall assessment of the general public. Of course, I can also be dead wrong; only the prophets that are correct get talked about, and the inaccurate predictions get dropped immediately. Regardless, Annihilation is a perfect science fiction film to me, and I feel that it is strong enough to warrant a retrospective article (also because we don’t have a review for it on Films Fatale, and the film still lingers in my mind after all of this time).

What has sold me so concretely about this film? Well, its ability to dismantle itself as it carries on is quite the impressionable achievement. The story takes place in a reality much like our own, but with an unveiled secret of a biological growth that is transmogrifying everything in its path known as the “Shimmer”. Annihilation is a five-woman trek down into the heart of The Shimmer in hopes of finding out its cause; it’s deemed a suicide mission from the very start. The closer we get to the spark point of The Shimmer, the more the film itself mutates to the point of cognitive deterioration. It’s a metaphysical experience that separates Annihilation from many of its contemporaries.

The more Annihilation progresses, the stronger its abstract elements get, to the point of taking over the entire film.

Of course, I bring up the contemporary sci-fi films that Annihilation is pitted against, because there is a clear influence of yesteryear: Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker. Similarly, the characters in Stalker are trying to reach an access point — this time it’s known as the “Zone”. Supposedly, a wish gets granted once visitors of the Zone enter the “Room” there. Stalker cuts from saturated sepias to incredibly detailed cinematography (in full colour, too) once the adventure really begins. It’s obvious that Annihilation has taken a few narrative and creative cues from this film, but that’s likely Garland’s doing. His understanding of Jeff VanderMeer’s source novel is deep within his hippocampus; he made sure to rewrite and direct Annihilation entirely from memory, as if to make his own original version entirely.

This modus operandi is exemplified in all of the moving parts of the film, as to tether all of Garland’s stream-of-consciousness directing to some sort of a purpose. The film begins with a basic title card, with similar chapter cards to follow in line. It ends with “Annihilation” being created and consumed by fractal convulsions. The score by Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow (the latter of triphop group Portishead) is conventional and driven by acoustic guitars; that is, until it transforms (of course). It ends up being a barely-recognizable series of minimalist pulses, more like the production work of Arca than the ear-friendly guitar strums from two hours ago. On first watch, a lot of the “safer” decisions feel like lazy decisions; every watch afterwards, they’re parts of a beautiful deterioration that happens before your very eyes and ears.

The world within The Shimmer is a gorgeously crafted one.

Even though the film is breaking apart (even in a narrative sense, as you are left to come up with your own interpretations for much of the final act), it’s actually getting more and more beautiful as you keep watching. As unorthodox as the creations of The Shimmer are, they’re production marvels. All of the plants that fuse together, the animals that split into pairs via mimicry, and the fungal warping of different beings into one prismatic wasteland is as gorgeous as it is hideous. Of course, the deeper into The Shimmer you go, the more deranged these creations get. You start off with a bleached alligator with many rows of teeth, and end off with the inexplicable; this truly is a new world.

The metaphorical contexts are all dependant on the characters that trek their way towards this unforgiving anti-paradise. Lena’s Green Beret husband Kane is presumed KIA, until he inexplicably just shows up at their home (in a way that even confuses you; is this a flash back? There’s no way he’s here…). Of course, this begs to be questioned, but Kane doesn’t remember anything (and his organs begin failing shortly afterwards). Lena is intercepted on the way to the hospital, and now she knows too much: Kane was a part of a military operation to find out more about this “Shimmer”, and is the only survivor to make it back out (he clearly isn’t in great health, either). Lena offers herself as one of the next researchers, and she teams up with four other women. The common ground is that each woman is broken in different ways, including a battle with addictions, suicidal tendencies, and the curse of the death of a child. Lena is unfaithful, and feels responsible for Kane’s decision to take part in what was otherwise considered a one-way ticket towards death.

Kane was the first person to make it out of The Shimmer alive.

Of course, we already know by now that Lena is the second person to make it out of The Shimmer, as the entire film is told from her recollections. She is being interrogated out of interest, but also because of some of her actions within The Shimmer. At the same time, it feels like she is being placed in the hot seat, and having to confess to her infidelities and self loathing. The Shimmer is a refraction of internal and external systems, so it duplicates what it senses. In that way, it murders each of its inhabitants in ways that are similar to their deepest regrets or loves. Cass Sheppard’s child died, and she is slain by a mutated bear and stolen from us too. Anya Thorensen starts feeling like she is going insane, and is killed by her biggest fears. Josie Radek comes to terms with her mortality, and becomes one with the Earth. Dr. Ventress’s cancer is slowly eating her away, so she devotes the rest of her biology to The Shimmer and is also at peace for a little while. Lena hates herself, so her final showdown is her literal facing of her depression, self destructive tendencies, and guilt.

Annihilation starts out like a more passive, mainstream sci-fi film before it becomes something more fragmented to the point of being borderline avant-garde (as far as big budgeted Hollywood films go, anyway). That sensation — that you feel like you are losing your mind — is a current filmgoing experience that I cannot shake off. It is so perfectly assembled. The small details are the final cherry on top, and I notice something new every time I watch Annihilation. These flourishes include the tattoo that Lena obtains from a corpse that The Shimmer implements onto her arm; appropriately, this tattoo is an ouroboros in the shape of an “8” (or an infinity symbol), capturing the endlessness of reincarnation, assimilation, and decomposition.

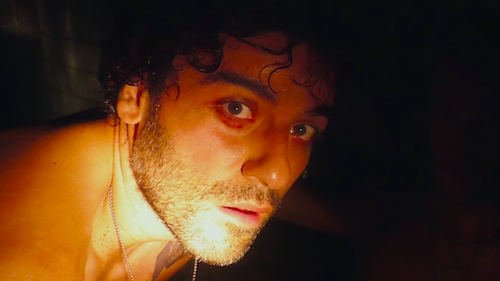

Lena has to face herself literally, as The Shimmer’s version of herself is her biggest enemy.

We conclude with Lena’s destroying of The Shimmer, which is created by her killing her clone with a flash grenade (and thus killing herself or her perception of herself, in a sense). The Shimmer crumbles around her, with trees shattering like glass, and leaves breaking apart into the sky. We are back with her in the present; she began her story confused, but she ends with some certainty, as she takes a sip of water just like Kane did earlier in the film. She is reunited with Kane, and we end with a close up of his eyes; this is the clone of Kane that was created by The Shimmer, and not the same Kane that Lena fell in love with, so his irises are constantly shifting colours. Then, we notice Lena’s do as well, and we’re left with the question of all questions: is this actually Lena, or did we hear her copy’s recollections of Lena’s final moments alive?

We will never know, and that’s kind of a beautiful thing. Garland’s previous film Ex Machina concerned itself with the Turing test, and whether or not a human could be fooled by a computerized being into thinking it is alive. Similarly with how that film ends, Annihilation guarantees the acceptance of one alien life (Kane), and flirts with the possibility of another (Lena), into civilization; we have consumed these new beings in the same way The Shimmer did with its own visitors. There’s something telling, there. In the way that one cell “dies” by splitting into others, and cancer engulfs anything that’s around it. In the way that the process of amalgamation means the destruction of what once was, despite the creation of something new. “Annihilation” means rebirth, evolution, and growth, and not necessarily the intention to break something in our own perceivable ways.

Annihilation is a mind blowing journey that carries the weight of mental illnesses, traumas, and existential fears on its back at all times. As fascinating as this adventure is (all of the elements of mystery and discovery, the imaginative world that takes what we know and reassembles everything, and more), it’s also mightily powerful as a personal facing of a much needed catharsis. Lena comes out a different person, whether it’s a new person mentally, or literally as a being that is made up of all new genetic makeup. Everything in this world kills its inhabitants, as inner organs twist, blood corrodes, and the nature around someone becomes their entire existence. As beautiful as life is here, it is also the cause of death. This bleakness is a powerful representation of the many ailments that we all feel. Stalker was a quest to have wishes come true. Annihilation is the hope that this pain would go away. Alex Garland’s opus is as intriguing as it is profound; it feels like a mental puzzle of inexplicable occurrences, but it’s really a flurry of statements, sensations, and experiences. It may not be getting its deserved love now, but I’m willing to bet that it will be recognized as the bold science fiction masterwork that it is.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.