The Best 100 Films of the 1930's

WRITTEN BY ANDREAS BABIOLAKIS

It’s the 1930’s! We have transported ourselves to ninety years ago, and are now well enough into the talking picture era that filmmakers have found ways to bypass the struggles with sound recording technology. After enough years of silent pictures, this new lease on cinematic life granted artists the abilities to retell the same stories but with a whole new angle. This meant revisiting literally the same films that one before, and remaking them with sound (like Hitchcock, Ozu, Lang, and other filmmakers would do). There were many other avenues, though: seeing what certain genres seemed like when translated into talkies, figuring out how music could now be utilized, and figuring out the time changes without the use of inter-titles and with sound. Of course, films also became much shorter for the most part, since many studios and filmmakers were abiding by the limitations of how much sound recording one would have (and, naturally, films became as long as their audio). The 1930’s contain the shortest average runtime of all of the decades I’ve researched by far (even the ‘20s had much longer films in general); many ‘30s films that I watched were an hour and a half, and even less.

However, silent films weren’t gone for good just yet. Some artists wanted to explore the era now as a style done by purpose, and not because it’s all that was available like it was once before. Some nations, like China and Japan, didn’t have the recording or theatrical technology yet, and so their silent eras carried on for a little bit longer. Other filmmakers were taking their silent films and dubbing over them, turning them into pseudo-talkies. Either way, a lot of movement was made, and I haven’t even discussed anything outside of sound, yet. This includes censorship that the Production Code enforced after enough pre-Code gems rocked one too many boats. There’s also the mastering of Technicolor that some directors and studios were getting comfortable with. The ‘30s was the Golden Age of Hollywood, but that Golden Age wasn’t really of one specific nature, particularly because of the many moving individual parts. It was, however, collectively a time of inspiration and wonder.

Here are one hundred films of the 1930’s, and picking out the best of the best, as usual, wasn’t easy. Which one hundred works best defined the most impressionable time in film history, when everyone was figuring out this medium again? Which features breathed new life into the rebirth of visual storytelling? Who made the big cross from silent pictures into the talking era? There are so many marvels of this time, and yet many pictures are tethered to key historical moments: the Great Depression, the lingering effects of World War I (in response to the rising tensions that would eventually cause the second World War), and other major events. I think these are the best candidates to illustrate all of the above; they’re also flat out the best films of these times. Here are the best one hundred films of the 1930’s.

Disclaimer: I am including documentaries and shorts — anything shorter than forty minutes or not labelled as a “featurette” (which were common around this time) — on another list, and they won’t be featured here.

Be sure to check out my other Best 100 lists of every decade here.

100. Pygmalion

The world today might be more familiar with the musical adaptation of Pygmalion known famously as My Fair Lady, but it is a very close rendition of the source play (that “rain in Spain” moment wasn’t a song originally, but it did exist as a vocal exercise). The 1938 film has an even more arrogant Henry Higgins, but the focus on Eliza Doolittle’s evolution via annunciation and presentation is much more pronounced than the adaptation that championed other elements of the story. Pygmalion is somewhat behind on the prevalent toxic masculinity, but focusing on Doolittle’s evolution in the film is well worth the time; you’re rooting for her, anyway.

99. The Crime of Monsieur Lange

Jean Renoir’s golden era had the visionary exploring genres and statements of all sorts. So, when something somewhat tongue-in-cheek like The Crime of Monsieur Lange comes along amidst the countless other styles he’s attempted (the same decade that birthed the ultimate satire The Rules of the Game and the beautifully intense La Grande Illusion), it can be difficult to know what Renoir is achieving exactly. Nonetheless, the director who held nothing back in his commentary ended up becoming a bit of a left-wing voice of sorts. Maybe it was the lack of cowardice in this film’s self representation, but Renoir’s political romantic blend was destined to make a splash, I suppose.

98. A Night at the Opera

During their best years, it honestly seemed like the Marx Brothers could do little wrong. as long as at least three of the family members were in some sort of shenanigans filled adventure, things would be foolproof. Still, A Night at the Opera wouldn’t be their ultimate success (that will be featured higher on the list), but it’s a prime example of just how good they were anyway. Every gag, pun, stunt or mistake was golden, and having the Marx Brothers tackle the elite was something I’m sure many audiences were feeling during the mid ‘30s. This relief from everyday woes is what the Marx Brothers specialized in, and watching privileged lifestyles topple along with them remains a treat still.

97. Gone With the Wind

Attached to heaps of controversy now, it’s easy to see what’s wrong with Gone With the Wind and its dated, problematic ways. Observing the film strictly as an entry in the history of filmmaking, Gone With the Wind is still a massive technical achievement that remains unparalleled for its time. The warm Technicolor, sweeping shots, and ambitious sets match the four hour runtime, and help to guide you through the many changing generations of Civil War era America. Experiencing entire lifetimes and movements here suddenly makes four hours not seem all that long, especially when the passion within the celluloid embraces each and every shot.

96. The Black Cat

Wait… Boris Karloff and Béla Lugosi in a horror film together while both were at the heights of their careers? Why, yes! The Black Cat feels somewhat like an extra gift for classic horror fanatics, given its nature and co-leads, but it’s still a mightily interesting psychological thriller full of uncertainty. Pitting both horror legends together — in what feels like a game of wits and spirits — is part of the appeal here, as we see both actors best one another outside of their famous monster roles. The shadows and dread come next, as The Black Cat takes a hold of you once you’ve fallen for its superstar bait; it’s deliciously deceptive in that way.

95. À Nous la Liberté

You know those musicals where it feels like anything could happen, and the power of singing would get you out of every situation? Well, À Nous la Liberté feels just like this, except with actual stakes involved. Featuring an escaped inmate that wants to succeed in life, we actually watch someone go from the bottom all the way to the top, all via the power of music. It’s actually hilarious, and René Clair’s satirical tone present throughout the picture only makes À Nous la Liberté feel a little patronizing (intentionally and in good fun, it seems). One way Clair’s picture can be read is that optimism goes a long way, I guess.

94. Stagecoach

We’ve come a long way since Stagecoach, but John Ford’s classic still can be recognized as a fantastic blueprint for borderline every single western afterwards. Taking place on the road with a series of characters, it’s as if Ford was opening up a book of western hopefuls for the world to attach themselves to (John Carradine was a favourite, but John Wayne ended up becoming the victor). Framing the countrysides of nineteenth century America, Stagecoach was an early indication that there was a future for these kinds of stories (even though the film’s politics are unfortunately heavily set in the past, we mustn’t forget). Still, every tale of dusty plains, small towns of yesteryear, and cowboys and cowgirls (under the general umbrella terms they now mean) are indebted to Ford’s early success.

93. I Was Born, But…

We will look at more silent Yasujirō Ozu on this list, but I just want to bring up the perfect marriage between the ways of silent cinema and Ozu’s picture perfect images full of so many details. Even though Ozu’s style would incorporate the static nature of silent pictures heavily, his earlier films contain a certain energy that he would abandon altogether. I Was Born, But… is such a juvenile angle that signature Ozu didn’t have, and even then he tells stories of immaturity and naivety with such heart and care. Ozu would later wish to dismiss all of his early works, but I find that even works like I Was Born, But… depict domestic life in Japan, the lower classes, and the joys and sorrows of life with the ultimate grace, and I find nothing to be ashamed of here.

92. Mutiny on the Bounty

The best adaptation of the uprising against Lieutenant William Bligh (and the novel about it by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall), Frank Lloyd’s Mutiny on the Bounty has a powerhouse cast (led by Charles Laughton and Clark Gable) driving the story’s constant tension. The build up to the titular rebellion is gradual, so you feel every ounce of disdain from all parties involved. The diverging into two different stories (one of survival to reach home, and one of building a new home elsewhere) all lead up to the legal battle that unites all forces — now individualistic in powerful ways — back together for a final explosion.

91. Trouble in Paradise

Bonnie and Clyde started with the former’s awareness of the latter’s thieving ways, or so the iconic film version would have you know. Well before that, a similar partnership in Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise, only both parties are established con artists in their own ways. That means there’s no teacher or student relationship, and both thieves develop their own ulterior motives, spiralling their ultimate heist plans out. Capturing the unpredictabilities of love, life, and even plan B, Trouble in Paradise is a film that enjoys being chaotic (by ‘30s standards, anyway); maybe two separate manipulators shouldn’t band together.

90. Le Million

Screwball comedies can become intentionally complicated. Released in the middle of the rise of this genre and after the sight-filled insanities of silent comedies is Le Million that aimed to get the best of both worlds. The premise is simple: a starving artist’s million dollar lottery ticket has been misplaced, and retracing the steps to find it becomes the bulk of this misadventure. That’s unlike screwball films, but the calamity that ensues is spot on. Almost like a Buster Keaton film (if it was a musical talkie and without the insane stunts, mind you), Le Million is both fantastic luck and bad luck, culminating into hilarity for all.

89. Little Caesar

Before films noir took off and the Hollywood Code ruined everything, the United States had it fair share of crime masterpieces (more to come later). One such case is Mervyn LeRoy’s Little Caesar, ran by tough guy extraordinaire Edward G. Robinson. As gangster sensation Rico, Robinson felt like the most unstoppable guy in film for a little while; foiling him is Joe (played by Douglas Fairbanks Jr.), who veers away from Rico down a less dangerous path. This only heightens the thrills of Little Caesar, since you are basically witnessing polar opposite outcomes clashing together (like the Hollywood that was to be, and the short lived current state of Hollywood with a thirst for blood).

88. Sisters of the Gion

After Kenji Mizoguchi’s ‘30s gem Osaka Elegy, he hit another home run within the same year with Sisters of the Gion: another tale of the human element of survival. The main unique idea in Sisters of the Gion is how both geisha sisters at the forefront react to upperclass privilege and sympathy differently, in the form of a successful man down on his luck. One sister aims to support him, while the other sees this as an opportunity to instil metaphorical revenge. These are parallels that run through all of Mizoguchi’s picture, creating dynamic characters that overtake the simplicity of the plot.

87. Dishonoured

The ‘30s was no stranger to the espionage romance, particularly to comedic effect. Josef von Sternberg seemed to try to take part in all of Hollywood’s ways when he migrated over, and this niche type of story was no exception. Dishonoured paired him up with Marlene Dietrich for the umpteenth time overall (third, here, although this was actually their first Hollywood film actually made despite it being released after Morocco), and she is the spy in question. In an era full of love triangles, last words on the war and/or heated political climates, and the search for the next star, Dishonoured was Sternberg’s way of wanting to have it all.

86. The Four Feathers

Zoltan Korda’s crowning achievement is being the right director to adapt A.E.W. Mason’s Mahidst War epic The Four Feathers (in vibrant Technicolor too, no less). Featuring exhilarating war sequences (even still), Korda’s version certainly feels ambitious and gargantuan in scale. Then, there’s the unforgiving heat that rises off of the film (that Technicolor isn’t doing the poor audience any favours in that regard), capturing the tensions between armies and even the people within each force (especially Lieutenant Harry Faversham, who now has something to prove to the world). Feeling like a test of survival and strength, The Four Feathers by Zoltan Korda is a war epic that continues to amaze.

85. Merrily We Go to Hell

Dorothy Arzner has been getting her dues in recent years, although the exploration of her hidden gems would be nice. That way, people would stumble upon something like Merrily We Go to Hell: a sharp take on a wife getting even and discovering herself outside of her marriage to a cheater with an alcohol addiction; her fling is a young Cary Grant before he was a superstar, no less. Arzner clearly knew how much she could get away with at the time, outside of her film being buried by the press due to its — gasp! — abhorrent name (oh dear). Today, this witty, unapologetic, and dry film demands your attention.

84. Grand Hotel

Out of historical context, Grand Hotel might feel like a series of unrelated stories just existing for the hell of it. Placing yourself in the ‘30s really reveals the true wonders of the film, even outside of its impeccable star studded cast. We have all walks of life post World War I, currently in the Great Depression, all colliding in an elite hotel with their own personal woes. The ending of the film might proclaim that “nothing” really happens at the titular hotel, but that’s not true. An overall nothing to us is everything to the players involved; life will always bend and shift towards a different direction eventually, and Grand Hotel managed to capture a snippet of one of its forms in a plethora of ways (considering its numerous storylines).

83. Street Angel

Muzhi Yuan’s Street Angel has become an undeniable political statement in the heart of the golden age of Chinese film, mainly because of its team placed at the front of its tale of a lower class uprising. These include artists, sex workers, and other forms of living disregarded by unfavourable politics. Rather than a means of depicting a successful rebellion entirely, Street Angel is more sympathetic, and understanding of the real kinds of unfortunate tragedies that lower classes have had to endure. The film speaks for many audiences (even still) because of its ability to see eye-to-eye with those that struggle, either by championing them or by understanding them legitimately.

82. Swing Time

Nothing in the musical genre went better together than the peanut butter and jelly of song and dance: Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Naturally, we’d have to have at least one film featuring this duo on my lists, and there is no better option than Swing Time, which encompasses all of the right notes of Golden Age musicals. Outside of the insanely problematic minstrel sequence (which we’re stunned hasn’t been brought up more amidst other popular examples of insensitivity), Swing Time has aged incredibly well, with triumphant number after triumphant number. It’s as bare basics as a classic musical can get, because it helped to set the tone for future show-stopping releases.

81. Queen Christina

No one could lead a romantic biopic epic like Greta Garbo could back in the ‘30s, and she did just that in Rouben Mamoulian’s Queen Christina: a tale of the titular queen of Sweden in the 1600’s. Able to capture mystery, yearning and power all within the same facial expressions, Garbo is captivating from start to finish. Queen Christina matches her complexity by showcasing not just her loves, but the politics surrounding her reign. In the end, someone who tried to achieve it all remains a royal with a title: a crown on top of an empty soul, forced to stare ahead at reality and what could have been.

80. La femme du boulanger

It only makes sense that a literary filmmaker like Marcel Pagnol would place so much emphasis on metaphors in a film like La femme du boulanger. We get a broken heart at the front of this fable, but really we’re staring at a suffering worker of the French lower class, who vows to tell his story. His refusal to bake — and contribute to society — results in a communal effort to get things back on track; is it for the betterment of the baker, or for what the baker can provide to his village? In ways, La femme du boulanger is sweet and saddening on a romantic level, but it’s also quite astonishing as a commentary on society through the eyes of one of its countless members; does all end quite as fantastically as it seems?

79. Make Way for Tomorrow

Leo McCarey sometimes got overwhelmed by wholesomeness to the point of a cheese overdose (Going My Way is such an example), but he occasionally knew how to get sentimental without being insufferable. Make Way for Tomorrow is one of his sweeter films, featuring an elderly couple forced to live apart during the Great Depression. We know the dark future of the financial crisis is only going to get worse, but McCarey used this opportunity to give one final day together between this loving couple, as they revisit locations, memories, and more. It’s a heartwarming piece that is authentic in how it connects with its audience, and it certainly is one of McCarey’s finest achievements.

78. La Chienne

Jean Renoir was a determined auteur at all points of his career, and he clearly wasn’t deterred by working with taboo subject matters. He went as far as to title one of his more tricky works La Chienne (“The Bitch” in English), and had four possible players that this vague-yet-foul title could represent. Could it be Maurice’s hateful wife, the sex worker that cons him, or her pimp that encourages this ploy? It could be Maurice himself, since life seems, indeed, to be a bitch for him. Without making anyone look particularly good (not even the vengeful Maurice himself), La Chienne allows misery to enjoy its company, in a time where filmmakers like Renoir were beginning to really test boundaries with talkies.

77. The Million Ryo Pot

Something about the ‘30s made fortune comedies trendy; perhaps it was the necessity to find humour in the darkest hours of a financial crisis. France had Le Million, but Japan’s response, Sadao Yamanaka’s The Million Ryo Pot, achieves the same effects but with even more intense results. Wackier, darker, and more elaborate (instead of a lottery ticket, this film features a map leading to treasure), The Million Ryo Pot also finds comedy inside of human desperation and greed: not the easiest accomplishment during a time when most citizens of the world were hurting. Sometimes, the absurd lengths we are willing to go makes for a fine, hilarious tale.

76. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

We have arrived right at the very first feature film to be fully animated using cels. It is, of course, also the first Disney feature ever: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Before the studio got invested in trying to capture art via illustration, they tested the waters a little bit with the exquisite backdrops and nature life found here. They ended up with another discovery: the studio’s knack for breathing new life in old fairy tales (which, as we all know, would end up becoming Disney’s altogether, pretty much). Right at the start was a film made by ambitious artists wanting to break ground. It was a more innocent time in Disney’s lore, and these efforts translate into timeless beauty.

75. Osaka Elegy

We would eventually get Sansho the Bailiff in 1954 and Ugetsu (his greatest achievement) slightly before, but Kenji Mizoguchi was already aware of where he was heading with his breakthrough classic Osaka Elegy. Always a voice for the working classes hit with extreme poverty, Mizoguchi places us in the challenging situation of a daughter willing to sacrifice herself to help her family make ends meet. Mizoguchi goes the extra mile and provides the uncalled for scrutiny that suffering martyrs make for the betterment of loved ones. Osaka Elegy is easily one of the more difficult films to watch in the 1930’s, but Mizoguchi’s excellent handling of sensitive and demanding subject matters is a revelation.

74. Duck Soup

At their very best, the Marx Brothers were doing whatever was necessary to stay on top. That “very best” is easily Duck Soup, one of the comedy genre’s longest strings of successful jokes and gags without a single flat note. Harpo gave up his signature harp. Groucho was at the forefront more than ever. Each Marx brother embodied the idiocies of politics, civilization, and the experience of living, really. Together, they made for a gang of lunatics that shouldn’t be fit to run a country, let alone their own lives (and yet here we are). Down to the final visual hysteria, Duck Soup is amazing smart-ass humour, and a film that is impossible to not laugh during at all (I dare you to try it).

73. People on Sunday

Some iconic films don’t tell massive narratives or have elaborate devices. They just capture life, and that’s exactly what People on Sunday, by Robert Siodmak and Edgar G. Ulmer, does. After World War I when Germany was recuperating, and before World War II, People on Sunday depicts non-actors performing as themselves, as if they were away from their daily lives for a second. Already poetic for this reason, the shifts of time have rendered it even more special: a moment in between two of the darkest hours in Germany. It might be unfair that histories beyond filmmakers’ controls can solidify a film’s importance, but People on Sunday is driven by fate: a calm, humble story amidst turmoil.

72. Mr. Deeds Goes to Town

Frank Capra loved telling stories for everyday Americans (as you will find many times in this list), so Mr. Deeds Goes to Town achieves his goal quite effortlessly. In a Depression-ridden United States, here’s a guy that just so happens to become the heir of fortunes. Mr. Deeds knows very little, but he knows that others are out to try and swindle him out of his newly found wealth due to his naivety. Well, Capra isn’t a sadist, so Mr. Deeds is of course going to be well intentioned. The ultimate payoff is the iconic declaration that Mr. Deeds himself is more sane and clever than the animalistic buffoonery of leeching opportunists, and it’s still a zinger that many of us can use today.

71. The Story of Temple Drake

There’s a lot of talk about the Hays Code, and there are clearly a ton of Pre-Code films that inspired such a set of rules to exist. Then, there’s one clear feature that essentially jumpstarted this new era single handedly. The incredibly difficult The Story of Temple Drake was telling a Hollywood story that the USA wasn’t ready to hear yet, placing the literary icon and her battles against a misogynist society on the big screen. Considered savage upon release, The Story of Temple Drake was a harsh reality that went against the sugar coating of an entire industry. We know better now, and can appreciate the difficult discussions the film was trying to have with a misguided society.

70. The Lower Depths

When Jean Renoir wasn’t trying his best to navigate around conventions and find new truths early on in cinema’s history, he went straight to the point without any misleading. The Lower Depths is an example of the latter, where the cinematic legend didn’t dance around the woes of lower classes living in the slums of the world. Even with a bit of a comedic tone at times, The Lower Depths is a harrowing picture, crafted by an auteur that was learning how to hand select specific tones at any given point. Released during the rise of his capabilities, this was a sure sign that Renoir was already well on his way to making masterpieces.

69. Frankenstein

While the starting point for the ninety year long erroneous mislabeling of The Monster as Frankenstein (pop culture can’t correct those who haven’t watched the film), James Whale’s adaptation of Mary Shelley’s classic is a gem of its respective medium in its own right. Perfectly capturing Shelley’s sympathy for Dr. Frankenstein’s creation, Whale created a horror film where the main source of fear for other filmmakers is actually a much more multifaceted portrayal here. Do we condemn The Monster for not knowing his place in the world, or how the world even works? Frankenstein was the best take of these two horror archetypical characters, until Whale would revisit this world four years later.

68. Morocco

Even before the romantic epic really took off, visionaries like Josef von Sternberg were looking to take up this genre real estate with big, superstar pictures like Morocco. The first Hollywood film with legend Marlene Dietrich to be released, Morocco was treated like the welcome mat for both icons; Dietrich acted alongside American mainstay Gary Cooper. Morocco seized the moment to go big, with ambitious sets, gorgeous lighting, and queer storytelling elements that celebrated Hollywood’s freedoms before the big Hollywood Code came and destroyed everything. Even though it wasn’t Sternberg’s first produced Hollywood film, Morocco was still quite the statement as to where the Austrian mastermind was willing to take Hollywood as an outside appreciator.

67. Only Angels Have Wings

In Hollywood, it was rare to be so drastically versatile that two motion pictures by one director were barely relatable. Howard Hawks was undeterred by such confinements, though, even at the start of his breakthrough. In the same era where he made us laugh with Bringing Up Baby and cower in fear with Scarface, Hawks crafted the epic Only Angels Have Wings, which is strung together with breathtaking flight choreography and action (both miniature simulation and the real thing). As invested with its flight lingo as it is with character development, Only Angels Have Wings is exhilarating after it is compelling. Sure, this kind of prolific poly-artistry is common now, but Hawks was keen on being the master of everything.

66. A Story of Floating Weeds

On my Best 100 Films of the 1950’s list, I brought up the gripping Floating Weeds, and how it was an opportunity for Yasujirō Ozu to rewrite his own history by adapting a previous film of his. Considering the blueprint, A Story of Floating Weeds, Ozu was already off to a great start. The finest silent film Ozu made, A Story of Floating Weeds felt like the major turning point in Ozu’s career, where he figured out how exactly to tell stories via still images (static imagery became his signature trait well after silent pictures were dead and gone); it’s no wonder as to why he wanted to revisit this film once he was at the height of his capabilities.

65. The Lady Vanishes

‘30s Hitchcock is so interesting, because this era feels the most like the British auteur was trying to perfect the genres that everyone else was partaking in (before he would rewrite them entirely himself). Even still, Alfred Hitchcock always operated on his own level, and a film like The Lady Vanishes is a great indication of this. What could have been a standard political mystery turns into a loopy, psychologically questionable case that will leave you guessing and fearful. Although Hitchcock is known for breaking rules and rallying against authority, it’s nice to see that he excelled even when he was obedient, with gripping works like The Lady Vanishes.

64. The Blood of a Poet

While Jean Cocteau’s more conventional work is still risky enough, seeing him fully unhinged is a complete luxury. His directorial debut was the entirely abrasive The Blood of a Poet. Partially inspired by the mythology of Orpheus and Eurydice (a tale he would revisit multiple times afterwards, with much more explicit influence), The Blood of a Poet is the abstract configuration of artists being consumed by their work in various ways (through four loosely linked vignettes). Completely ruthless with its dedication to this avant-garde portrayal, The Blood of a Poet doesn’t quite care what audiences think of its interpretations, and that’s partially why it’s so impossible to turn away from.

63. Fury

By the mid ‘30s, Fritz Lang was beyond comfortable within the era of talkies, and already had created a couple of masterpieces (to be seen shortly on this list). So, something like Fury was barely the testing of waters, and more like an artist trying to see what else they could do after conquering their medium multiple times. Arguably a proto-noir that contains the tropes of the upcoming style, Fury is completely warped by heartbreak, misguidedness and guilt. Placing an icon like Spencer Tracy in the midst of wrongful conviction and loss only seals the deal; Lang understood cinema enough to fully get Hollywood, and it was now his latest playground.

62. Westfront 1918

Some artists of the Weimar era didn’t fit the mold of the political uprising in Germany of the early-to-late ‘30s. This includes the works of G.W. Pabst, whose brilliance was silenced by morons like Joseph Goebbels. One such example is Westfront 1918, which is a realistic take on war, intended to honour those that fight. As the first sound picture Pabst made, he utilized the war grounds as recording studios, soaking in as many audible references to World War I was possible. As inventive as it was artistic, Westfront 1918 is an astounding success that only hateful fear mongering puppets could manipulate as anti-patriotic, when it was meant for the people to feel and experience.

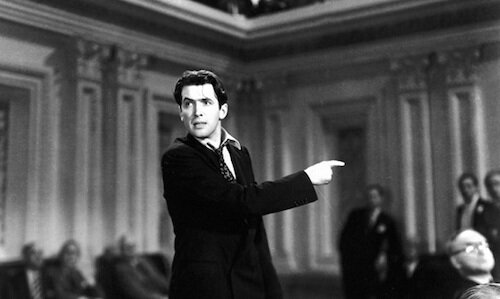

61. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

Right after winning another Academy Award for You Can’t Take It With You, Frank Capra was well on his way towards another fantastic Jimmy Stewart outing, and the best one of the ‘30s: Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Here, an everyday person is given the opportunity to become a politician, representing his people. Unlike some Pre-Code or upcoming noir films, Mr. Smith is optimistic, even amongst all of the naysayers and the corruption. Capra isn’t about that life, though. He was always a positive, wholesome filmmaker that wanted to remind viewers of the good in people. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington does just that.

60. Humanity and Paper Balloons

Japanese talkies came a little bit later than Hollywood, so two things happened as a result: they had some great late game silent films, and their sound pictures avoided many of the early-era gaffes of other nations adapting to new technology. So, something like Humanity and Paper Balloons can set a precedent for Japanese films from thereon out: capturing the attention to visual detail of Japanese silent films, whilst establishing a proper voice for viewers (and not just via representation in this instance). Sadao Yamanaka’s opus sorts through authoritative oppressions and impoverishment with ease, and the aesthetic flair leftover from the more artistic silent era only helps you keep glued to the pulp of this narrative.

59. Craig’s Wife

Wedged in between the adaptations by William C. deMille and Vincent Sherman is this Dorothy Arzner triumph based on the original Craig’s Wife on Broadway. Arzner was always excellent at teaming up with greats before they broke out, and this film’s instance was finding Rosalind Russell to play Harriet Craig. We spend a day with Harriet, and see what she nurtures and how. Russell is perfectly stoic, and her work under Arzner feels so natural and authentic; something the other male-guided adaptations substitute for emphasis. It takes a lot to bring a Pulitzer winner to the big screen, and clearly a number of competitors took the Craig’s Wife challenge; Dorothy Arzner’s textured approach reigns triumphant with us.

58. Shanghai Express

After trying to go massive, Josef von Sternberg seemed to dial things back with a minimalist approach in Shanghai Express. Confining most of the film onto a small train and with the same familiar faces for a majority of the duration, we’re looped in to all of these passengers’ personal tales. One step away from being an Agatha Christie production, Shanghai Express features many motives without everyone going over the line; we’re still aware of the businesses of all, though. Shanghai Express gets you engrossed in many overlapping personal voyages, as motives begin to blur or pop out unexpectedly, all underneath a fantastic illumination amongst shadows.

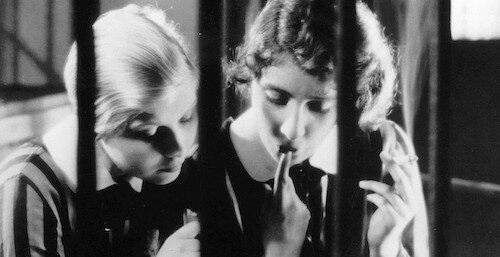

57. Zéro de Conduite: Jeunes Diables au Collège

Jean Vigo accomplished so much in his tragically short career, and the midway point was a featurette that contained so many universes in such a short amount of time. During a time where the education was still disastrously abusive, Zéro de Conduite: Jeunes Diables au Collège wanted to provide some sympathy via juvenile retaliation. An imitator, if…., goes the extra insane mile. Zéro de Conduite is content enough with just giving the oppressed students a voice, without any purely malicious revenge. It’s the kind of whimsy that Vigo was always reliable on extracting out of his stories and spilling across the entire screen. As much as Zéro de Conduite is meant for all, it’s for all of our youths, too.

56. 42nd Street

Lloyd Bacon was one of the better directors at bringing the showtime musical productions onto the big screen, with incredible numbers that would close out his features. 42nd Street is one of these cases (another to be featured shortly), with a whole narrative about a struggling production having to be headlined by a shy, newcomer star, after relentless practice with the intended star (who has to opt out). It’s a Golden Age musical: it’s going to go okay. We know that. The main attraction of a Bacon feature like 42nd Street is what that “okay” looks like. It’s an instance of turning your mind off and just enjoying the show (the first two thirds of 42nd Street is a showbiz story as to at least give the film enough meaning). Once the final number hits, nothing else matters.

55. Le Roman d'un tricheur

Ah yes, the good old unreliable narrator: a narrative device that truly sticks with you if used effectively. Well before French New Wave or Left Bank movements were a thing, Sacha Guitry releases something like Le Roman d’un tricheur: an hour and twenty minutes of pure expository meandering. From the creative title display on, everything is golden, even if taken with a grain of salt. When cinema was still trying to figure itself out (especially when sound got thrown into the mix) and know where it stood, here comes Guitry with a deceptive narrator that talks for every character (literally) whilst, essentially, gloating about their escapades. It’s rather audacious, really.

54. Young Mr. Lincoln

The best John Ford film of the ‘30s (sorry, Stagecoach) is this interesting take on Abraham Lincoln, not as a biopic, but as a snippet of his legal years. Young Mr. Lincoln assumes we already know how Lincoln was as a president, so it puts work into showing us a side we maybe weren’t as familiar with, in an enticing courtroom drama (which may not be as honest as Abe and veer a little far away from the truth of the real Duff Armstrong trial, but I don’t mind). With a breaking-out Henry Fonda as Lincoln (basically the ‘30s version of casting Tom Hanks as Fred Rogers), Young Mr. Lincoln is charming to start, but ready to get stern as justice is sought after.

53. Pépé le Moko

The greatest film of Julien Duvivier’s career was the proto-noir crime drama Pépé le Moko. It uses already-stale tropes ironically: as fodder for new and exciting elements. A stolen heart becomes the means to iron out a scheme. A protagonist is actually fully guilty, despite the film’s support of him. New opportunities are only their own variations of entrapment. This sounds old hat since we’re familiar with films noir, but Pépé le Moko wasn’t taking this from previous films. Hell, I’d argue the film came out before there were even any real whisperings of noir at all. If Pépé le Moko didn’t help to influence noir, it certainly predicted how beloved the style would be (and how adventurous it could become).

52. Stage Door

After Morning Glory, Katherine Hepburn starred in an eerily similar role in Stage Door, which, furthermore, mirrored her own life: an artist of wealth still wanting to make it into show business. The point is Stage Door was a different take on this, with an all star cast of female legends, including Ginger Rogers, Lucille Ball, Gail Patrick, and more. The featured sisterhood feels disrupted a bit by Terry’s (Hepburn’s) inclusion, as if their aspirations differ greatly from her own, and it is ruining the order of things (although the real actress and her cast gel together perfectly). Even with best intentions, Stage Door doesn’t remain closed for any opportunity, including heart wringing tragedy, all in the name of putting your entire soul on the line for your passion.

51. It’s a Gift

Considering all of the great W. C. Fields flicks, there’s still undeniably one film that stands head and shoulders above the rest: Norman Z. McLeod’s It’s a Gift. This comedy about starting a new life released during the Great Depression is somewhat of a relief from big changes that many people were having to make, even though It’s a Gift was more about the impending promise that’s to come (although that’s squandered by hindrances, shenanigans, and many deceptions). From the quick mess-ups to the lengthy, unstoppable gags, Fields was at his top form here, with a brief slapstick bonanza that is sure to be identifiable with anyone that has ever had to make major adjustments.

50. Love Me Tonight

When talkies brought in the possibilities of moving stage musicals onto the big screen, it seemed like that was enough to get going for at least a few years. Nope. Some filmmakers still wanted to stand out from the pack, and Rouben Mamoulian did just that to start Love Me Tonight with a bang: a series of everyday noises that clump together to make a fantastic initial impression in the form of a cohesive song (far more difficult to pull off back in the ‘30s than now). Afterwards is a more typical musical narrative: a financial scheme brought off course by one’s fleeting heart. Either way, even this is done well, allowing Love Me Tonight to carry on strong as one of the decade’s most interesting musicals.

49. Marius

The ‘30s were graced with the compelling Marseille Trilogy that started out with a big enough bang: Marius, by Alexander Korda. The trilogy takes in three different perspectives, and we kick things off with the titular young man that is at a crossroads of life. On its own, Marius is a standard drama with enough emotional oomph to be memorable. At the start of a sensational trilogy, Marius is the harbinger of things to come, and the very moment that life changed for all three title members. Fanny is a direct result of Marius’s actions, and César is the aftermath of causation. Marius had to be there to make all of this work, and it does its job well.

48. King Kong

As fun as many big monster pictures are, there’s still the one that started them all; dare I call it the king? I do love Godzilla myself, but King Kong set a fantastic precedent. Even though the special effects are far too old to even be considered dated, it’s well enough made that none of that matters. There’s still the rise — the discovery of the gargantuan the titular gorilla — and the fall — the iconic New York City showdown, when Kong is displayed against his free will. King Kong is the exposé of what humans perceive to be spectacles, and what life itself has created far beyond our capabilities (ironically, the fake gorilla is somewhat faithful to this notion).

47. Kameradschaft

The finest G. W. Pabst film of the ‘30s is a euphoric tale of perseverance in a time where many viewers could desperately use the motivation. Inspired by the real Courrières mine disaster of 1906, Kameradschaft places French workers in a collapsing shaft, and Germans in the opportunity to help them. The key here is that Pabst moves this story to after World War I, and starts the film off with French and German children being separated by society; the youth of the world have their hatred instilled in them by civilization. Kameradschaft isn’t concerned with that, but rather the uniting of opposing forces, and the instilling of faith in humanity during a crisis.

46. Holiday

Of course, romantic comedies are meant to be sweet and fluffy, but George Cukor’s Holiday figured out new ways to bring life into one’s heart. Incorporating many small personal tropes — I love the little music box moments myself — renders Holiday a little private space between lovers, and who could ask for more than one of the best Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant affairs? Holiday isn’t about falling in love, but the extents one will take to meet approval to fulfil the promise of a blossoming romance. All of the little things matter. Hepburn and Grant knew this, with their unstoppable chemistry, and Cukor recognized this, with what he chooses to highlight in this humble film.

45. Angels with Dirty Faces

James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart together in a gangster classic? Now that is peak crime cinema casting in the 1930’s. Before Michael Curtiz became known as the guy that brought us Casablanca, he really was all over the place tonally, but Angels with Dirty Faces may have been his finest feature (well, before, again, CASABLANCA). Despite Rocky’s evils, seeing him face the hand of fate is devastating beyond belief; Cagney was as moving as he was frightening. The efforts a priest goes through to persuade a new generation of impressionable kids to not join a life of crime may not have gone as well as he had hoped. However, as far as cautionary tales go, Angels with Dirty Faces is a loud enough statement on how a life of evil isn’t really a life at all.

44. Earth

Alexander Dovzhenko was making waves alongside his fellow Soviet game changers when he was two films into his Ukraine Trilogy. The final say on the matter was Earth: a silent expressionist opus that didn’t care if the world was moving onto talkies. Making a powerful statement on the importance of retaining visual artistry, Earth is more metaphor than plot (although it does involve an intense tale of life and death), with nature and agriculture taking up much of the photographical and narrative space. With images of growth, wilting, rain and sun, Earth is a commentary on prosperity and legacy: an aesthetic fable that pertained heavily to the politics of Dovzhenko’s time.

43. Bringing up Baby

There are screwball comedies, and then there’s the insanity within Howard Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby. It’s befuddling that this film could have been considered a failure upon release, when it has become such an inspiration for comedy ever since. Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn bookend a real leopard (the titular Baby), and that’s all there is to it (although the subplots that Baby crashes through do heighten the craziness of the entire affair). How could anyone not like seeing Grant jump out of his skin? Well, the ’30s don’t know what they were missing. Bringing Up Baby is indisputably a comedy classic that merges situational hilarity with mass confusion, and it’s all so splendid.

42. La Bête Humaine

There could not be a ‘30s film more attached to French pop culture royalty than La Bête Humaine. Directed by Jean Renoir and based on the classic novel by Émile Zola, this industrial fable places two misfits onto one train to see what sparks fly: a jaded engineer, and his love interest who is plagued with guilt. Well before noir even took off, a film like La Bête Humaine hit all of the right notes, cementing itself as a proto-noir that fits in perfectly amongst the style’s classics. Framing the setting’s train as if it were a character, La Bête Humaine lines itself up to create an ungodly climax: the opportunity for life to overcome those that inhabit it, in an almost too literal, heartbreaking sense.

41. Footlight Parade

Lloyd Bacon’s opus couldn’t have had more going for it. Footlight Parade is led by song-and-dance-man legend James Cagney, with the musical sequences directed by Busby Berkeley. That means Cagney’s portions are hilarious, magnetic and intriguing (watching him fumble between making movie house prologues, down to his unfortunate prophecy of how disastrous Cats would be). Then there’s Berkeley’s irreplaceable showtime sequences to wrap up the film, and they have to be the best in all of musical history (the synchronized swimming number especially). It’s unfortunate how problematic the final “Shanghai Lil” number is conceptually, because it puts a damper on a musical masterpiece.

40. The Adventures of Robin Hood

What’s a film list without at least one Errol Flynn sword flailing affair on it, especially if it pertains as mightily as The Adventures of Robin Hood? The definitive take on the historical figure, this collaboration by Michael Curtiz and William Keighley is such a leap forwards for cinema. The choreography surpasses many other swashbuckler epics, given the scope of Robin Hood (and Flynn himself couldn’t have been cast in a more opportune part). The Technicolor is some of the best of its time, painting the well known story in stained glass hues that represent the Middle Ages with pure style. The lore of Robin Hood run deep, but they have never been as well showcased as they are here.

39. The Only Son

The filmmaker with the best capabilities of capturing all of the facets of domestic life is Yasujirō Ozu, so it’s no secret that The Only Son is such a moving depiction of societal desperation. Placing the onus on both parent and child — when there really isn’t an onus for how life just works out sometimes — is a special trait of The Only Son: as if life was squandered even with the best efforts put forth. Luckily, this is an Ozu film, so there will always be a mutual understanding, between Ozu and his characters, performers and the camera, and souls and the audience. Even in the face of disappointment, The Only Son gets how life can be unforgiving, but its players can carry a little more heart.

38. César

The final chapter of the brilliant Marseille trilogy has the distinction of being the only film of the three to be directed by author Marcel Pagnol (who created a new script as a continuation of his “Marius” storyline). César feels hopeless in tone, and it’s a perfect way to wrap up a story full of so many conflicts and twists. Pagnol revealed that he had a few revelations up his sleeve even still, by placing them late into César (as to change the entire trilogy at any given point). Desperation turns into hope — with a nod to fate — that the entire trilogy could use. Pagnol was meant to tell this tale, and any medium was his oyster.

37. My Man Godfrey

A lot of butler jokes in comedies come from the absurdities that arose in Gregory La Cava’s impossibly hilarious My Man Godfrey: one of the finest screwball insanities to ever be produced. Part of the appeal is William Powell at his absolute best, delivering some deadpan gold for the ages. Place him in the middle of a manic family during their own breakdowns, and you have a man that wishes he was confused amidst a screwball (or screwy, really) predicament. Lies become misunderstandings, and not even those with control of the situation fully understand where everyone lies; at least there's always room for sharp banter, when glares won’t do the trick.

36. Freaks

There are barely any films that cause such a difficulty to discuss like Tod Browning’s Freaks, mainly because it still feels like a work that is daring enough to remain taboo. Chastised upon release by bigots that disapproved the use of lives that were condemned to circuses by these same bigots, Freaks feels completely different with a more understanding audience. Labeled a “horror”, I feel Freaks is actually more of a love letter to the many souls that have been cast aside by hateful hearts (even if they seek vengeance on the intolerant, here). Regardless, the film is still effective, but the sympathy can be better understood by those who are willing to find it.

35. Borderline

After the rise of talking pictures, silent films — when not made by Chaplin or nations that were still making the change over — started to transform from expressionist to avant-garde. Kenneth Macpherson (of The Pool Group) found empty real estate in silent cinema, aching to be used by progressive voices. The only real frame of reference we have to the collective’s visions is their last remaining film Borderline, which was heavily interested in interracial relationships and the discussion of society’s treatment of different pairings. Heavily artistic in tone, Borderline is almost solely driven by heart; this includes pure rage. Sadly, there isn’t much else to currently explore of The Pool Group cinematically, but their impact will forever be felt.

34. The Public Enemy

I’ve highlighted James Cagney as the musical superstar that he is, but let’s face it: society remembers him for being a gangster, because he was one of the best of this world, too. One of the first instances where the world was certain of this is William A. Wellman’s crime opus The Public Enemy, where we see Cagney’s Tom Powers get hardened and heartless over time, as he rises in the underworld. Even with all of the red flags that The Public Enemy tosses our way, Powers still gets more and more corrupted, and his villainy is impossible to ignore. Even with the “don’t say we didn’t warn you” cheesiness of the finale (it gets a pass, since the ‘30s is littered with these kinds of lessons to audiences to bypass censors), The Public Enemy is quite grim for its time, and the kind of edge that gangster flicks benefited from.

33. The Testament of Dr. Mabuse

Fritz Lang was having one hell of a career breakthrough after the silent opus Metropolis and the crime masterpiece M. This was all of the incentive in the world for Lang to revisit another great work of his once more: Dr. Mabuse the Gambler. It only made sense that he made The Testament of Dr. Mabuse with bigger budgets, better filmmaking skills, and sound (even though he was always a masterful director). Taking this antihero tale and dialing it up to a thousand (with spooky effects, dark sets, and complete insanity), Lang proved that old tales can be brought back if done right. This didn’t prove to be true with The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse in 1960, but it was his final farewell to film, so it is forgiven.

32. Dodsworth

It might seem like a tall order to pick the best William Wyler film of all time, considering the breadth of his filmography. However, one strong contender — far more than any epic he made — is the heartbreaking Dodsworth. It oddly enough shows more restraint than many Wyler works, because its emphasis rests on the ever-growing space between two spouses who have to finally come to terms with their inevitable lovelessness. Even though Dodsworth is very much in the now, a lot of the film feels like it is the result of decades of gestation, like a real marriage that was worked on to no avail. Yes, Wyler made a lot of great films, but not many come close to the poetic precision of Dodsworth.

31. The Scarlet Empress

Out of all of the Hollywood films that Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich worked on together, the greatest success is the Catherine the Great epic The Scarlet Empress. The first two acts feature a political situation on the brink of boiling over, all the more provoked by a ruthless and suave Catherine (obviously Dietrich, because there was no one who deserved the role more at the time). Of course, disasters that aren’t tended to tend to become catastrophes of gargantuan proportions, and that’s where The Scarlet Empress heads: complete domination. Sternberg films this with complete style, filling up a small frame with the exact amount of details for you to dig through, even when death is afoot.

30. Fanny

The second instalment of the Marseille trilogy winds up being the best, because it is the strongest entry in a series known for its twists and turns. Starting off after Marius, we’re already aware of the titular traveler’s departure for his own benefit. César tries to clean up the entire mess left. Well, Fanny (the film) is that mess, and Fanny (the character) is subjected to society’s sneer and fate’s curse. This is where the trilogy really becomes overwhelming; you could almost declare it the series’ heart, at this point. Full of the most intense moments and saddening outcomes of Marcel Pagnol’s story, Fanny wins in an already stellar triptych.

29. The Bride of Frankenstein

James Whale’s Frankenstein was already great, bringing Mary Shelley’s classic novel to life (or back to life, we should say). How could it get any better? Well, it did. The Bride of Frankenstein expands on Shelley’s lore with prophecies: what would happen if Frankenstein’s monster developed awareness and individualism even more? What would trying this experiment again look like, and what would Dr. Frankenstein’s motive even be? Somehow, revisiting the same electrical machines, devious set ups, and difficult integration into society doesn’t get tiresome, because Whale has different motives for each similar element. It ends on the birth of the title character, whose brief presence still steals the entire film, given how she was written and what she represents: new life in a horror sequel that miraculously is better than the previous film.

28. Boudu Saved from Drowning

Sometimes, a discussion doesn’t have a definitive answer, and that’s okay. Jean Renoir learned this early on, and was willing to prove it with his satirical fable (of sorts) Boudu Saved from Drowning. The titular vagabond is saved from suicide, and brought into society to be tended to. You can see this as civilization trying to force shared ideas onto an existentialist or outsider. Boudu is far from a likeable protagonist, and it’s this dodgy line (that Renoir adored) that makes his film a bit of a puzzle to try and figure out for ourselves. I don’t think Renoir was trying to explicitly say anything with Boudu Saved from Drowning, outside of presenting a peculiar circumstance for you to decipher yourself; if only more cinematic conversations were actually open to the public.

27. The 39 Steps

Alfred Hitchcock loved going the distance with his films, and it’s part of what made him an innovator. However, what would a film of his look like if he kept to the basic fundamentals of cinematic storytelling? You might get something like The 39 Steps, which carries very little flair but packs all of the narrative goodness an espionage mix-up thriller requires. The film gets right to the point and stays there, without encouraging much musically or trying to persuade you visually. Hitchcock recognized that John Buchan’s original novel was enticing enough, and so this particular recipe didn’t require many extras. As a result, The 39 Steps is as pure as Hitchcockian cinema can get; it’s well written enough to never feel dry or tasteless, too.

26. The Blue Angel

I’ve spotlighted many of Josef von Sternberg’s Hollywood adventures on this list, but I have to be honest. The greatest film he made was while he was in Germany, and that feature is The Blue Angel (or, specifically, Der blaue Engel, since the English version of this film is not even nearly as good for a multitude of reasons). The best of the Sternberg veterans (Emil Jannings and Marlene Dietrich) compliment each other, only to subsequently clash together, in this cautionary tale of complete devotion to the point of losing one’s own individuality. The Blue Angel seems promising at first, before it dips into its borderline sadistic third act: a reminder that not every major decision we make is for the best. Unlike a few of his American features, The Blue Angel is Sternberg at some of his darkest moments, and it combines comedy and tragedy so effortlessly.

25. Wuthering Heights

How many filmmakers have made Emily Bronté’s Wuthering Heights? Outside of Kate Bush’s soaring pop tribute, the greatest rendition of this Victorian era classic is William Wyler’s magnum opus, starring then-rising star Laurence Olivier and established thespian Merle Oberon (as “Cathy”). As frigid as one’s ghost and the winters that confine us into claustrophobic hiding, Wyler’s Wuthering Heights is as passionate as it is spiteful, and every single ounce of intent is felt. Playing like a remorseful confession, all of the recollections in Wuthering Heights sting, knowing that these are the final memories of a life now lost; we’re actually witnessing eternity from the great beyond, but that element is savoured for the right time.

24. The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum

The films that made Kenji Mizoguchi an untouchable auteur are the allegories of life that he created out of other worlds. While he was finding his stride with works like Osaka Elegy and Sisters of the Gion, he was figuring out the best ways to depict struggling working class people. Then, he ventured towards the life of theatre performers — particularly Kabuki theatre — with The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum, and found parrallels between on-stage devotion and one’s self sacrifices for society. It’s Mizoguchi at his most comfortable in the ‘30s, with stunning lengthy takes and gradual progression, turning this song of artists into a full symphony.

23. Camille

George Cukor excelled at conveying every emotion in his films, but he was singular in his ability to create passion; he figured out how to recreate those indescribable butterflies and chills. Camille is stuffed to the brim with these sensations, and from scene one, this bittersweet affair is toying with your heartstrings. This ultimate love triangle — chosen by someone whose time is dwindling — is difficult on every turn, but Cukor never relies on hate or anxiety to make this dilemma impactful. Instead, he weaves in uncertainty: will any of this matter? Time is precious, whether it pertains to how we figure out our lives, or how an artist makes the most of their creation’s duration.

22. Partie de campagne

When a cinematic genius is working in top form, even a smidgen of their final feature is golden. That is somewhat the case with Jean Renoir’s unfinished-yet-fully-complete film Partie de campagne. Although it was released in featurette form in 1946, Partie de campagne is still a film of the ‘30s, tucked away by a master who was forced to delay his naturalistic poem due to weather complications. In this briefer form, we have a day-in-the-life of many, only for all lives involved to leap ahead, leaving us to fill in the gaps ourselves (it’s almost nicer this way, given the passive-yet-fleeting ways of the film). In this state, Partie de campagne is nostalgic for salad days, knowing that everything else will pale in comparison afterwards.

21. Limite

The sole film by Mário Peixoto is one of cinema’s strongest “what if?” scenarios. Shunned for its experimental depictions of thoughts and memories, Limite seemed like a brick wall for the first time director, who took this as a sign to quit before he even got ahead. Now, Limite is rightfully considered a Brazilian cinematic staple; it ultimately was an open door that reception slammed closed. Outside of the few auteurs that were influenced by its surreal symbolism and carefree tone, what else could Limite have affected? It remains a stand-alone circumstance: a silent statement that pushed the boundaries of what visual cinema could be, beyond what most were ready for (apparently).

20. Mädchen in Uniform

The Weimar Republic’s art scene took pride in how progressive and non-conventional it was, and it has been a textbook era in courses for its more abstract uses. Then, we have Leontine Sagan’s Mädchen in Uniform, which openly portrays queer love literally and figuratively in 1931 (could the romance that develops between an authoritative figure and a student also be a commentary on shattering the lines between society and the power hungry?). Being forward thinking is one thing, but the truth is Sagan was a masterful storyteller, with Mädchen in Uniform being so effective even just as a conveyer of feelings, storylines, and tones. This is a romantic drama that is a must for its era (and all eras, frankly).

19. Port of Shadows

Marcel Carné was still testing out his filmmaking capabilities when he reached his second feature Port of Shadows. Clinging closely to the poetic realism ways that French cinema was fixated on at the time, Carné was just tagging along when he made one of the movement’s finest features; that would be enough, if he wasn’t accidentally aligning himself with proto-noir as well. Think about it: the necessity to start a new life, abandon one’s past, and lose everything for change, love, and freedom. Even though it isn’t entirely in love with cynicism like many films noir, Port of Shadows has a really obsidian way of depicting the crossing of thresholds.

18. The Wizard of Oz

Duh. I don’t really have to say much else, but let’s get to it anyway. The Wizard of Oz is one of the greatest family films, a fantasy marvel, a Technicolor staple, and so many other important designations. Acting somewhat of a bridge between the silent era’s unique take on fantasy with the ways of the future (the Tin Man could have been in Metropolis, for all I know), The Wizard of Oz is a pivotal moment in cinema’s ethos. Then, there’s just the fact that it’s such an imaginative feature, being so mesmerizing and heartwarming that it can break the “woke up from a dream” role of story writing and it doesn’t even matter.

17. The Awful Truth

What makes for a really good screwball comedy are the repercussions of what is actively happening. So what if a couple is separating in The Awful Truth, only for them to secretly still love one another and vow to ruin each others’ chances of finding love elsewhere? That almost sounds old hat. It’s the lengths that these characters go and the end results that place The Awful Truth as one of the genre’s greats (well, certainly one of the funniest examples, anyway). Could you ask for anything more than Irene Dunne and Cary Grant being petty towards one another? I guess you can say that The Awful Truth is an obtuse way of saying “I love you”, but that sounds like a joke in and of itself.

16. Baby Face

Pre-Code Hollywood really was a different time: a small snippet in time when anything was game, and I can only imagine how far these kinds of stories could have gone had the Production Code not kicked in. One of the most mentioned examples of this unique era is unquestionably Baby Face, with Barbara Stanwyck’s Lily being the figurehead of every film that spat in the face of early talkie censorship. No matter which version you watch (but, preferably, the uncensored original), Baby Face is a rebellious flame of a feature that laughed at toxic masculinity, the limitations placed on women by society, and other tropes that were already becoming too familiar in Hollywood.

15. It Happened One Night

One of the great early successes in the 1930’s was a cinematic event that continues to carry that exact same weight, no matter in what capacity you watch it. Frank Capra made It Happened One Night before he became fully enveloped by tenderness and sugar, even though it is still warm enough to be noticeably his own. Even with the selfish desires of either major player — played out by Claudette Colbert and Clark Gable at the top of their games — It Happened One Night is more about the discovery of idiosyncrasies between people (the things that make us human, no matter who we are).

14. Vampyr

After making The Passion of Joan of Arc (one of the greatest silent films ever), Carl Theodor Dreyer was ready to enter the world of talking pictures. However, he wasn’t keen on making a talkie entirely just yet, so he explored the former cinematic world of silent expressionism one last time (although he had soundscapes and palettes at his disposal). The end result is Vampyr: a trippy, nearly psychedelic horror picture that plays out the darkest corners of one’s mind. Transcending past typical horror tropes by being a well made cinematic experiment first and foremost, Vampyr is a visual, audible feast for any cinephile to have at.

13. Ninotchka

Ernst Lubitsch's possible greatest achievement is a very tongue-in-cheek jab at both Russians and the French (while also somewhat mocking the ridiculousness of the classic Hollywood romance, so toss in Americans too). Ninotchka is almost completely self referential, especially behind Greta Garbo’s hypnotic work as the title character (her side glances and eye rolling is exactly what I mean). Without going too overboard in self worth to the point of arrogance, Ninotchka is incredible fun, whilst still having the right amount of brains to still satirize the idiocies of political friction. Some golden Lubitsch years were still around the corner (pun intended), but this was the second last time (and final moment of brilliance) for Garbo, unfortunately.

12. Modern Times

Still discontent with making talkies outright, Charlie Chaplin held out with silent (or mostly silent) pictures for as long as he could; he did so with the ironic statement on changing eras called Modern Times. This was the last feature of his iconic Tramp character, who was now finding himself amongst an equal: a homeless woman, whom he vows to help. Between his silly factory work (classic Chaplin in nature), and the progression of the story’s trek into the big wide world, Modern Times is fierce with its joking about society’s fixated capitalist ways, but it also feels like Chaplin going out in complete style. It’s a major final bow to both the Tramp and silent films in the only way he knew how: excellency.

11. Scarface

Sure. Other crime films of the ‘30s could try and continue what Howard Hawks made with his pre-Code opus. Brian de Palma tried to capture the excessive nature of Hawks’ vision with his own remake. Truth is, any imitator of Scarface pales in comparison. As visceral and raw as gangster films in the Golden Age of Hollywood got, Scarface is a savage retort to both censorship boards and those that valued crime works as a means of influencing viewers to stay out of trouble. Paul Muni is absolute dynamite, inhabiting the film’s chaos and instigating some of his own anarchy. It’s easy to see why Scorsese, Tarantino, and, yes, even de Palma, were so obsessed with Howard Hawks: because Scarface channelled New Hollywood before the code that killed the Old Hollywood came into place.

10. Alexander Nevsky

Sergei Eisenstein was always a film making perfectionist, so knowing that he collaborated with Dmitri Vasilyev well after his silent film explorative days means they were clearly destined for one another. Such was the case, as Alexander Nevsky is an exquisite crusade film for its time. Even though much of the duration is dedicated to combat, seeing how Eisenstein and Vasilyev framed bloodshed, choreographed devastation, and illuminated death is such a feast. One can see Alexander Nevsky as a propaganda film for the Soviet Union to champion them over Germany, when politics were starting to boil before World War II. That might be, but Alexander Nevsky is still filmmaking excellence, made by one of the medium’s finest visionaries, and a director who was on the same page as him for this triumph.

9. All Quiet on the Western Front

As soon as talkies could permit anti-war sentiments, All Quiet on the Western Front was there to claim the spot as the finest Hollywood war film of its time (and arguably ever, depending on who you ask). Its brief moments of joy embrace the cheesiness of ‘30s storytelling, before spiralling into some of the darker elements of pre-Code Hollywood; endless war sequences that prove just how long the nightmare goes on for. A return to society only feels even more foreign, before Lewis Milestone opts to savour a poetic ending to mask the largest moment of brutality here: the slaughtering of innocence.

8. Le jour se lève

The strongest example of proto-noir is Marcel Carné’s attempt to find beauty within the derranged with Le jour se léve. Instead of a protagonist remembering their woeful past, François is virtually moments away from death before his life flashes before his eyes; his visions get broken up by reality, as he has to prolong his life before getting lost in his thoughts again. The danger matches all of the Hollywood gangster flicks of the time (that Hollywood was no longer even able to fully endorse once the Production Code was established), whilst carrying a lot of artistic significance via the poetic realism movement of France. Life — and how it wraps up — can sure be peculiar.

7. The Goddess

While China was still releasing silent films, Wu Yonggang seized the opportunity to create a rebellious statement on the vicious ways of society’s judgemental eye with The Goddess. It starred Ruan Lingyu with the greatest silent performance since Renée Jeanne Falconetti, performing as a sacrificial mom whose methods to support her child are shunned by others, thus condemning her and her son’s livelihoods. The Goddess doesn't let up, as it is unafraid of what cinema was fixating on and forcing other storytellers to conform to: the happy ending. As it progresses, The Goddess secures itself as a relentless depiction of perseverance and damnation.

6. M

After solidifying himself as one of the most powerful auteurs of the silent era, Fritz Lang was ready to conquer talking pictures as well. Well, he certainly didn’t abide by any rules or even warnings. Before the Production Code was set in place, M — Lang’s first talkie — still seemed to go against the grain and resonate as arguably the darkest film of the entire decade. Sound allowed Lang to use this innovation as a torture device, by letting his child-murdering antagonist whistle “In the Hall of the Mountain King” whenever his psychotic urges resurfaced. Presenting the story mainly from the villain’s perspective, M certainly was made by an artist who vowed to destroy the foundations of the industry he dominated only moments earlier.

5. La Grande Illusion

What is the titular illusion of Jean Renoir’s war masterpiece La Grande Illusion? Is it the idea that war is made by humans and benefits no one? Is it the audacity to think that fleeing a POW camp would actually be doable, and that the fugitives would actually live free lives afterwards? Could it be the idiocy of believing that a survivor of war won’t be plagued by traumatic memories for their entire lives? Whatever the case may be, La Grande Illusion is an escape film on many fronts, which wraps up with an ambiguity that lingers with you as much as the entire journey does. It’s a war story for the ages.

4. L’Age d’Or

After the groundbreaking surrealist short Un Chien Andalou, Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali seemed like a filmmaking duo for the rest of their lives, right? Wrong. Dali gave up after helping Buñuel write his feature debut L’Age d’Or, so Buñuel ultimately figured out the rest of his cinematic voice himself. As screwy as the previous short (this time with the gift of sound design to really destroy the reality of everyday objects and activities), L’Age d’Or is a fever dream of aristocracy that grows more and more perverted: sexually, mentally, and artistically. It took a short while for Buñuel to really take off as one of the great auteurs afterwards, but L’Age d’Or was an early indication that the greatest satirical surrealist of all time finally found his home.

3. City Lights

When the rest of the world was moving towards talking pictures, Charlie Chaplin was more interested in discovering the purity of cinematic art. His greatest achievement (amongst many other masterful works) is City Lights: his final fully silent picture (Modern Times was a great bridge between both worlds). The Tramp is back once more, but in a world of poetic realism (although he is still subjected to ridicule and slapstick). Even though it’s a Tramp comedy hour through and through, it’s the humanization of this character and the world around him; the way he falls in love this time around (and with whom), the way life changes depending on the tone of the film, and Chaplin’s proof that he knows exactly how motion pictures work. With arguably the greatest ending in film history (certainly the most beautiful), City Lights was the moment that Chaplin became one of cinema’s filmmaking legends.

2. The Rules of the Game

No matter how many Jean Renoir films I have on this list, we mustn’t fool ourselves as to what his best film is. The Rules of the Game was a ruthless satire of the bumbling idiots of the upper class, left to their own devices and wrecking havoc within a confined space. The film is paradoxical, hence why it’s such a championed work in film history. Its depictions of its characters are careless, but Renoir couldn't have been more selective with his choices. After the Production Code, The Rules of the Game seemed to hit all of the Hollywood stereotypes on the head, place them in France, and have them try to revert to unsavoury ways once more. Whether these were cinematic rules, societal rules, or moral rules, The Rules of the Game was Renoir’s way of saying he could not give less of a damn, and we’re all the more grateful for this.

1. L’Atalante

One of cinema’s largest crying shames was the short life of Jean Vigo, who passed away at twenty nine from tuberculosis. He was just getting started when he released what was his only feature-length film (excluding featurettes) L’Atalante, early in the decade in 1934. He died a month after the theatrical release of this film. There wasn’t even a chance for us to see what he could do next. He redefined poetic realism, aesthetic filmmaking, and cinema altogether in the span of an hour and a half. All he needed was a newlywed couple, the titular boat, and for life to take its course. Then came magic, and L’Atalante certainly feels like one of the medium’s most mesmerizing achievements.

Capturing all of the elements of marriage (happy, toxic, successful and failed, all at once), L’Atalante feels like life has sped by us, even though there is no indication of this, judging by the characters and their realistic states. Still, Vigo crafted entire lifetimes and rebirths in this heavily metaphorical journey, full of silly laughs, heavy woes, and all of the oddities in between that make life the greatest experience. If that weren’t enough, there’s the flashes of Vigo as a visual artist, utilizing filmmaking tricks and techniques to pull off the kinds of prettiness and celebration that only this art form could fulfill.

Jean Vigo clearly could do it all; as sad as it is that we only had his short filmography, it’s a testament enough that we could tell his brilliance with so little. L’Atalante is unquestionably the definitive cinematic poem: a love letter from a careless, jealous husband to his freedom loving wife. It doesn’t take much for the greats to make their mark, and Vigo single handedly made the greatest film of the 1930’s while barely seeming like he tried; this feels like it was second nature to him, and he was ready to really get going with his capabilities. If only he lived long enough to see how much his masterpiece has affected countless audiences for decades.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.