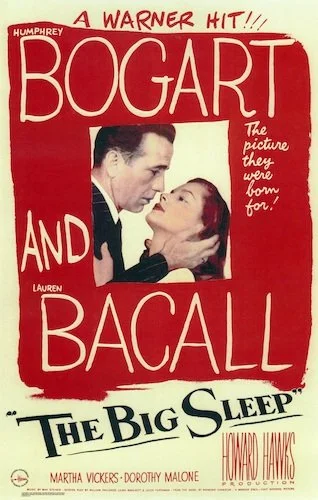

Noir November: The Big Sleep

Written by Cameron Geiser

Every day for the month of November, Cameron Geiser is reviewing a noir film (classic or neo) for Noir November. Today covers Howard Hawks’ beloved The Big Sleep.

So what makes a Noir film a Noir? The sub-genre has been notoriously hard to pin down the details of what exactly makes a film a Noir, but when one hits all the right marks, we know it to be true. There’s always the tried and true guidelines to go by; scenes set at night, in the rain, usually involving murder and a femme fatale or two. Though a common inclusion is that of the lead male character either starting out as weak, insipid, or slowly devolving over the course of the film until they are subsequently defeated, or just run down and lost in existentialism. That's not the case with The Big Sleep.

Philip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart), was described by the author that created him, Raymond Chandler, as the detective that was ultimately victorious, but still lonely, still mired in that existentialism. “I see him always in a lonely street, in lonely rooms, puzzled but never quite defeated.” This was before Chandler got into the screenplay business though and it was up to William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, and Jules Furthman to adapt his novel. Which they did exquisitely. Indeed this Noir had a trifecta of excellence with Humphrey Bogart as the lead, Howard Hawks as the Director, and a near perfect screenplay that went through the ringer in terms of rewrites, additions, segments excluded, and reworking generally up til the release of the film. So while Marlowe may not have entirely fit the preconceived notions of what a male lead in a Noir film should be, Bogart’s no nonsense performance as Marlowe had enough charisma and calm-under-pressure finesse that this notion can confidently be discarded without pause.

Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in The Big Sleep.

This film also has a reputation for being difficult to parse through, or not easily understood from moment to moment. I’d say that while not every moment makes sense in a linear, literal fashion, it all combines to create an appropriately nightmarish and otherworldly atmosphere. So what's it all about anyways? Marlowe is called upon as a private eye by General Sternwood (Charles Waldron), a wealthy wheelchair bound patriarch whose two daughters have gotten themselves into a web of troubles. The General and Marlowe get along finely as the old man tells the detective that he'd appreciate a look into his younger daughter's “gambling debts”. Marlowe agrees but notes that the General's youngest daughter, Carmen Sternwood (Martha Vickers), was indeed the type to attract dangerous attention as “She tried to sit in my lap while I was standing up” upon his arrival. Before departing he's met by the older daughter, Vivian (Lauren Bacall) who's keen on finding out what her father hired a detective for. She suggests the real reason her father hired Marlowe is to track down his protege Sean Regan who had disappeared a month prior. From there Marlowe follows leads, dodges suspicious suspects, finds a new corpse for every corner he crosses and generally keeps his cool despite the increasing body count and ever moving motives amongst a growing set of potential murderers.

Giving away the plot would be pointless here as the film's experience as a whole is what makes it work. This may just be the best writing within the classic Noir films as well. Marlowe may have been a more outwardly bigoted character in the Chandler novel, but Bogart brings the even keeled detective to life without souring the character as much as his original depiction. In fact a lot had to be changed or depicted with more innuendo and word play to carefully sidestep Hollywood's censorship with regard to the Hays Code that prohibited direct language about, or depictions of, many of the aspects involved with this story. Several of the suspects, case leads, and informants connected to the story were involved in pornography, or other sexual persuasions (no homosexuality allowed onscreen in those days), amid a myriad of crimes. The writers and director had to work around all the violence and how it was depicted, not to mention Bogart's Marlowe is very much the subject of lust and its implied that he has sex with many of the women involved.

Yes, we may get all of our information through Marlowe's perspective so we're not always in on every detail- but that just encourages the audience to be the detective themselves. Doggedly trying to solve the case alongside Marlowe has only further preserved this film in cinematic amber. A little bit of earned mystery with a satisfying conclusion is enough to seal the deal for The Big Sleep. Yes, the film was remade in 1978 with Robert Mitchum and James Stewart- but to a lesser quality in my opinion. This one still holds up, and it's worth your time.

Cameron Geiser is an avid consumer of films and books about filmmakers. He'll watch any film at least once, and can usually be spotted at the annual Traverse City Film Festival in Northern Michigan. He also writes about film over at www.spacecortezwrites.com.