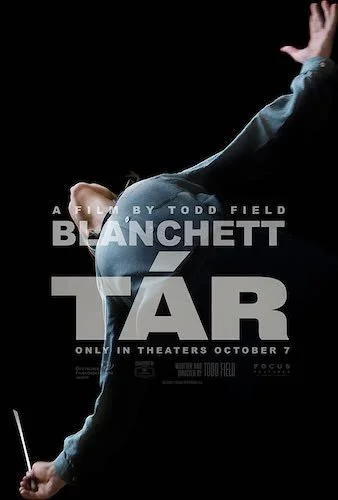

Tár

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: This review contains major or minor spoilers for the film Tár. Reader discretion is advised.

Sixteen years after Little Children, Todd Field is finally back with his latest assessment of the hidden psychological turmoils of humble America, but he’s far less blatant with these studies this time around. Tár stars the titular conductor extraordinaire Lydia Tár: a cosmopolitan, highly accoladed legend of modern classical music (although she is a fictional character pertaining just to this story, but Field does a brilliant job making this feel like a biographical picture). We face her daily life and her eventual downfall, but Field is absolutely brilliant at making this story feel natural; for someone that has only made two other feature films, he is clearly meant to make motion pictures, and he has an authorial hand as both a director and a screenwriter that feels unrivalled. Tár, again, is about a music conductor, but I bring this up a second time whilst discussing Field because it is important to know how much he seems to compose and conduct his film like Tár herself. The very opening is a vulnerable shot of Tár asleep, with a phone recording her, and mocking messages overlaid above her still body. Shortly afterward, we hear Tár discuss how Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 starts not with the note that we think of (that booming, stuttering intro), but rather with an eighth rest (and it is up to the conductor to play this silent note, or sorts, and cue everyone else in). That’s exactly what Field does here: he begins the film with a rest, and sets us up for the rest of his symphony.

Then there is the overture, and Field and company have the sensational decision of placing the technical credits (and some other ones) right at the start of the film. We get to hear the music of Lydia Tár, uninhibited, and unaffected by scrutiny and scorn. We get our own little private ceremony (or you can look at this opening as a blind audition process: the kind Tár and the rest of the Berlin Philharmonic elite hold to find new pieces to fit into their orchestra). Finally, after some time and with Field’s lulling us into a hypnotized state, Tár begins with an afterthought: exposition in the form of an interview with Adam Gopnik of The New Yorker, who is not afraid to ask some provocative inquiries and use Tár’s answers as fodder for the next question in line. Field’s symphony is patient at this point, and it looms. Almost everything on screen is wooden like a woodwind (not to be redundant), golden like the brass section, and black and white like the keys on the very piano that composes all of these songs. The film itself feels intentionally glacial, as if we are present with Tár at all times, waiting for the right moment to strike. As the film proceeds, it indeed does pounce towards the conductor-composer and point its finger at her. It is at these moments that Field gets that staccato editing going, the pacing up to a maximum, and all of the colours of prestige and meaning get washed out. He is in charge of the film just like a conductor, and this alone is worth the price of admission.

Tár boasts elegance and purity from almost every single element, even during the more cynical and hostile moments.

I just want to single out one particular scene where Field’s directing is some of the best I’ve seen in years, and it’s toward the start of the picture (and one of the early signs of Tár showcasing her relentlessness and inability to listen to others). Tár is teaching at Juilliard and is critiquing a student conductor’s work. The student detaches themself from classical composers because of their problematic histories, and they pinpoint some key examples. Tár identifies as a lesbian woman that has had a tough time in the industry herself, and tries to see eye-to-eye with the student, but she also is able to separate the artist from their art. The student isn’t, and Tár begins to belittle them out of frustration. This sequence is told in one long shot, and the camera’s placement for each step of this scene is exactly where it needs to be, whether we are right next to the fidgeting student (and noticing how uneasy they are feeling), or seeing the teacher up close and the student blurry in the background (as Tár looms from atop the lecture hall over the targeted student). This is the kind of scene that can be deconstructed beat-by-beat in film classes for years to come, and it is breathtakingly composed.

Fortunately, this display of precision is shown early in the film, because it will force you to look for this same attention to all details from here on out, and let me tell you: virtually everything in Tár has purpose (either blatantly or abstractly). After these preliminary set ups, we finally get the ball rolling and see the true intention of the film. Tár is preparing for an upcoming recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, and she is struggling (not to compose, mind you, as even these mental blocks seem to be overcome by her slowly and surely, but just in general). She can’t sleep. She is antsy. We quickly learn not to feel too sorry for her, though, as the film introduces us to how much Tár uses her power to shut other people out, whether it’s the restaurant server bringing her more water (without a simple “thank you”) and her suffering neighbour (a daughter taking care of her terminally ill mother), to the people she supposedly loves the most (her wife, her assistant, and other key figures); the only person Tár seems to actually nurture and show love for at first is her adopted daughter, Petra.

Quickly, Tár becomes transfixed with a young cellist (whose presence during the blind audition is known, thanks to her loud, signature heels that clomp into the rehearsal space); she is qualified and talented, but Tár clearly fancies her and is preparing her for something else. By now, we are learning that Tár is predatorial. Her assistant is another groomed person that is at her wits’ end with Tár. We also have a subplot of someone named Krista Taylor, who is adamant on getting in touch with Tár via a bevy of emails sent with the utmost urgency. Tár ignores them without a second thought. This leads to one of the first major pivotal points of the film, when you really start to see what it is all about: the most realistic, unbiased portrayal of cancel culture in a film thus far. Everything seems to just organically happen in this feature until it begins to collapse. We can see all of the red flags from a mile away, but it makes sense that Tár herself doesn’t in the way that Field concocted this film. You will feel like life is just existing, and that everything that transpires is exactly as it would be if it happened to us: a sudden questioning of “how in the world did we even get here?” when all of the signs were as clear as day. A perfectionist, narcissist that destroys their own work that they spent decades building: this happens quite a bit, and Tár is quite aware of how this actually transpires.

Cate Blanchett delivers one of her greatest performances of her illustrious career as Lydia Tár.

This downward spiral is pieced together beautifully, and the film concludes with much of what was initially shrugged off being the only methods for Tár to now survive. In reality, she was working towards a self analysis for the world to study: Tár on Tár. What she got instead was her being her own worst enemy and self imploding in spectacular fashion: how is it that someone that is so perfect as a conductor and score writer so terrible at composing her own self? By the final act, she is cancelled for her continuous predatory attacks, and she seals the deal by accosting and beating the conductor (who happens to be manager of her fellowship) at the eventual performance of the music she spent the whole film writing and rehearsing (but, again, she was cancelled, and forced out of this event). Even though the conclusion aftereward is the briefest part of the film, it packs enough narrative juice to really stick the landing, between the revelation that Lydia Tár is actually Linda Tár: a lower-class member of New York that abandoned her family when her career took off and shed off any signs of her American roots (ahh, there’s that side of Field’s storytelling). Even her family doesn’t want her back, considering how she burned them for decades since. The fact that Field can save such an important piece of exposition for the very end of the film and have it not feel wasted is truly masterful.

She has nowhere to go, because she erased who she once was (her upbringing), shattered her legacy (her iconic career), and any chances of where she can go next. She is now in Vietnam and learning about the permanent ripple effects of artists going too far to the detriment of themselves and those around them, with Francis Ford Coppola’s alligators from Apocalypse Now still breeding and contaminating the rivers there. She is told to pick a masseuse — clearly also an escort — from a group at a local parlour, and her history of violating young women for her own personal gain catches up with her, and she gets sick to her stomach. All of these signs of her monstrous history (both as an artist and via her art) will now forever haunt her, but her return back home reminded her of one thing as she watched her nostalgic Leonard Bernstein VHS tapes: music will forever be there for her. It’s all that she has now, that she has pushed everyone away for good, and no one loves her (not as a musician, not as a genius, not even as a friend or wife). We see her perform a score for a video game at a convention, and then the final film credits appear, with a dubstep remix of classical music. Tár has gone against everything that she has ever believed in because she has to: she threw it all away.

Tár is played perfectly by Cate Blanchett, and this is easily one of her best performances yet (which is saying a hell of a lot). She fully embodies the role of being a mastermind composer/conductor so effortlessly. Despite her not donning any deceptive makeup or hairstyling to mask who she is, I occasionally forgot I was even watching Blanchett act. I fully bought into this performance at multiple instances, whether it was her fluent easing in-and-out between German and English, or her piano and conducting feeling so real (the scene where she plays one piece via different styles is Oscar worthy). She savours moments of terrifying anger and deep sadness for the exact moments that they’re needed, and the rest is as authentic as a performance can be. Not once did this chaotic role feel melodramatic, when it easily could have been an opportunity for a thespian to chew at the scenery. This is also credit to Field’s impeccable writing of this title character. We see all of the parts of her daily routine that are used for very specific payoffs later on. She is a runner, and so this leads to her sprint-and-slip (where she lands on her face) later. She practices boxing, and this makes her fury of fists towards her replacement feel even more painful. Even that one-shot sequence is now finally edited: by a TikToker to make Tár say things she didn’t at all say (but all of the words spoken earlier all matter, even if we didn’t think they would at the time). Virtually everything in this film is there for a reason, and that’s a nearly impossible achievement in a three hour feature.

Tár is so precise with what it wishes to show, and every single moment is savoured.

I feel like I can only wrap up with the extra garnish that Field uses that boosts this film towards being the current best of the year, after everything else has been said and done: the flashes of Tár’s actual human side. She is a loving mother, even if her methods aren’t orthodox (it’s never appropriate to threaten a child, even if they are bullying your daughter). When she chases after cellist Olga and sees that she lives in squaller, she is partially scared for her safety (a sign of privilege), but also saddened by this realization that a loved one is living a difficult life (both sensations are conveyed without a word of dialogue by Blanchett). When she showcases sympathy for her neighbour’s dying mother, it’s still too late: Tár has been so awful to those around her that her offering of condolences fall on deaf ears. Do we feel sorry for Tár? No, but it’s nice to see that we can still have depth in characters good and bad. Tár feels real, and that’s what is most important. She never seems evil in her own mind or by design, but because she has lost sight of what goodness is, and you can fully believe that the rare instances where she is grounded. It’s not enough to warrant sympathy, but it’s there to at least help us connect with her in any capacity.

I don’t know what else to say about Tár: my current film of the year. Hildur Guðnadóttir’s score is only used when the Berlin Philharmonic plays (there isn’t any non-diegetic music in the film at all), and even in these sparingly-used cases, it feels so magical, as it takes you to a new place (and it helps us believe that Tár, who is meant to compose these pieces herself in the film, is the best in her field). Monika Willi’s editing is a contender for the best of 2022, as there is a clear display of knowing when scenes should start and end (and how cuts can be used effectively, particularly that jump between Tár’s fall and the smashing of a rolling pin on a cutting board). Watching the film devolve cinematographically (from monochromatically ambitious to naturalistic) helps us follow the film in a purely visual way (we can pinpoint when Tár begins to lose her legacy). Everything (just everything) feels exactly as it should here.

I cannot stress this enough: Tár is exemplary. Even with all of this in mind, I feel like it won’t be everyone’s cup of tea: I can sense that the film will read as slow or uneventful for some movie goers. For me, however, I was breathless the entire time. This is a film that knows exactly how to feel subtle yet powerful, purposefully long yet riveting, and enriched yet neutral. We have a new modern American classic on our hands: a balancing act between so many different ideas and themes whilst feeling in control the entire time. I always felt like Todd Field was an underrated filmmaker, and his absence for nearly two decades maybe doesn’t help with this issue, but Tár will be impossible to ignore this awards season, whether it’s just for Blanchett and the technical elements of the film (another reason why the crew’s credits were shown at the start of the film) or for the picture and all of its components (which should be the case, but you never know with awards season politics). There are many great films that come out each year, and I’m thankful that film is such a generous medium in this way. Not many films feel as confident-yet-humble as Tár, though: a motion picture that is as rudimentary as it needs to be, and yet it is also astoundingly pioneering.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.