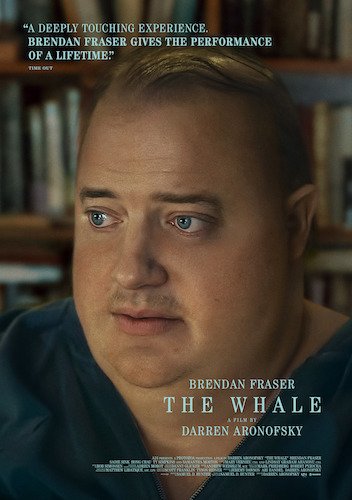

The Whale

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: minor spoilers for The Whale are in this review. Reader discretion is advised.

I don’t see how anyone would be watching a Darren Aronofsky film based on an already-polarizing play (by Samuel D. Hunter) expecting it to not be at least a little mean. If there was ever a director that frolicked in the miseries of others as they are at their absolute worst physical and mental states, it’s Aronofsky. Having said that, The Whale, the oft talked about latest feature from the Harvard filmmaker, is possibly the first time he overstepped his boundaries (at least a teensy bit). The extra sounds of gurgling and sloshing that follow Brendan Fraser’s character Charlie feel like the overkill. I adore Aronofsky’s films and would rank him in my top twenty favourite directors of all time, but he definitely explores subject matters heavy handedly. It’s kind of his forte. It’s how you feel like you’re being kicked again and again in his works. In The Whale, however, we get the message loud and clear and it almost feels like the film is as judgemental as those that gawk at the protagonist Charlie.

Then again, I think the film is driving home a very depressing point that may justify the staunch stance The Whale has on, well, all of its characters (we just see it the most with Charlie), and it’s one that you can either feel is right or doesn’t cleanse the film of its cynicisms at all (this is easily the most mean spirited Aronofsky film yet, unless you think Requiem for a Dream has it beat). You can feel that the film shames overweight people, but I don’t see a single person that comes out of this looking cared for by the film’s gaze. The central point is that every single person has their own white whale to chase, much like in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, but the majority of us chase this allegorical whale and kill ourselves in the process. We either self destruct or get sick looking for that of which cannot be fixed. In this film, we have a handful of characters, but the main role is Charlie: an English professor that has eaten himself to morbid obesity after the death of his boyfriend. He refuses to seek medical treatment, and he states his number of reasons why (I’ll not discuss these as to not spoil the film; you’ll see what I mean once you view it), but deep down we know that he hates himself. Every single person in this film hates themselves accordingly.

His estranged daughter Ellie swings by his house once he has offered her money in an attempt to reconnect, but she is beyond frigid with him; you can’t blame her when you find out that Charlie left his family to be with his partner. Ellie seems to despise everyone and everything, though, and she even seems to like torturing others in the same way she felt burned by her own father. His ex-wife, Mary, is an alcoholic. His nurse, Liz, is his only real friend but she has her own major resentments (I’ll leave those for you to discover). Hell, even the well-intentioned missionary, Thomas, is “sent by God” to try and save Charlie, and yet he has his own baggage. Every single person is carrying weight. You can consider Charlie to be a metaphor of this, but I think that would be quite disrespectful if that were the case. Instead, I see Charlie as someone with an eating vice that is slowly trying to murder himself. The film, to me, isn’t trying to be anti-fat: it’s driving home how much Charlie resents himself. However, I can’t blame anyone for feeling like The Whale loses sight of this goal and hurts others in the process. It is proverbially trying to do the same as all of its characters: chase meaning for existence. Like its players, The Whale is far from perfect. It’s up to you to decide whether or not it deserves to be loved.

Brendan Fraser gives the performance of both his lifetime and a generation as Charlie in The Whale.

I think it’s safe to say that everyone’s reason for pushing through The Whale, regardless of how they feel, is the mighty return of Brendan Fraser: a star that was once easy to only appreciate in short doses (or so his projects made him seem) that I now never want to stop acting (not that I wished for him to ever quit, mind you). Not only is this the best performance of his career, it’s flat out some of the strongest acting I’ve seen in years. It’s one thing that Fraser is given some of the most convincing makeup work 2022 has to offer. Seeing Fraser fully embody Charlie in every single way was devastating to watch. You can sense years of regret and self-punishing anguish in almost every glance Fraser provides. There’s also that one element that we all knew he had from the get go: his signature charm. He will warm your heart in any single scene, especially when the rest of the world scolds and abuses him. It’s actually painful to watch at times, because Fraser makes Charlie a gentle soul that doesn’t want to hurt others or himself anymore.

The rest of the small cast is quite great, with Hong Chau’s conflicted, gruff, and loving Liz, Ty Simpkins’ annoyingly cheerful Thomas (a missionary that will soon crack and reveal his inner turmoil), and an always-welcome brief performance by Samantha Morton as Charlie’s addicted ex wife. Sadie Sink is strong as daughter Ellie, but I found her to be a little insufferably negative at times; this is no fault of Sink’s, who seems to be able to do exactly as she is told (and reasonably well, actually, no matter what the project is), but I do blame the writing for making her feel a bit single-note. Then again, I can at least say there’s a reason for this constant anger and spite. The Whale tries to showcase that everyone cares, even if they pretend not to. Ellie is the most difficult case Charlie tries to crack, and he’ll die trying. I do understand this mission, but it doesn’t make Ellie any less flat at times.

As The Whale continues, and we get deeper and deeper into the psyches of all of the tortured souls on screen, I couldn’t help but feel like the pandemic brought a similar narrative out of all of us. We either forced ourselves to finally get to those dreams we’ve been chasing our entire lives (to mixed results), or punishing ourselves and feeling more fragile and on-edge than ever. The Whale goes to the extreme with these mentalities, mind you, and it is much bleaker as it initially insinuates that we are a neglected species. We’ve been abandoned, left to agonize ourselves. It’s Charlie that reminds us that there is more to life, and after the exhibition of moral awfulness that is the majority of The Whale’s runtime, he still tries to teach us (the professor that he is) that people are “amazing”. It’s how I know that the film is purposefully overwhelming with its negativity and ugliness (again, not the best look depending on who you ask): it wants Charlie (specifically Brendan Fraser’s Charlie) to shine as the moral epicentre of the toughness of life. You can be at your worst, close to death, having lived a terrible life, and still capable of finding care, hope, and love. It seems audacious and almost insulting, but there’s something endearing there.

Finally, The Whale has a running concept about the importance of truth (raw, untainted truth), and that could be where some of the film’s excessive hostility comes from (I’ll however complain that there’s not much truth to post production sound work to make Charlie seem more grotesque as he walks, but that’s just me). No one likes having a real dialogue anymore because we’re all at our wits end. Our patience has run dry. The Whale is a hideous film because of how vicious everyone is to one another. It’s a bit hard to look past, but I’m also an Aronofsky fan. I’ve seen every single film of his (some many times) and actually expect to feel like shit after his films are done. It’s tricky to take on something like morbid obesity and have the same angle, however: you’re guaranteed to hurt viewers if you strive to make your audience feel low with such a subject matter (even with the best intentions). For me, The Whale is pessimistic but soulful, haunting but with the tiniest pinch of hope, and another cinematic charley horse kick from Aronofsky. It feels impossible to find love amidst so much darkness, but that’s kind of the point of the film (that doesn’t mean you have to feel like it works). By the euphoric conclusion, I could accept The Whale for its occasional misguidedness and limitations because of how much it did work with me. I’ll conclude by saying that this film is not for anyone, but I don’t think any films by Darren Aronofsky — the master of polarizing features — really are.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.