Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Darren Aronofsky Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Fame

Darren Aronofsky has made quite a few polarizing films. In fact, everything outside of his debut has repulsed or bothered viewers to varying degrees (some films much more than others). Yet he continues to be heralded as one of the best filmmakers of our time. I think it’s because he goes far beyond shock value with his works. A Harvard graduate that specialized in both film and anthropology, Aronofsky became transfixed behind the camera while going on trips and shooting wildlife and communities. Despite how intense his films are (and how challenging they are to the mainstream audiences they’re often marketed for), there’s one underlying theme in every single one of his works: a quest to find one’s reason for existence. This is something he likely pushed himself to find while studying the lives of others outside of his zone of familiarity, as we all have different personal quests and ambitions.

Raised in a Jewish household but not quite a super religious man himself, Aronofsky also has an interesting religious dichotomy in his films where he breaks down why faith doesn’t work for him while insisting on proving that it does for others: it’s an atheistic angle of acceptance and interest that you don’t see too often. No matter what each film tackles, you will always find despair, with hope dangled in front of our protagonists. They may chase it via faith, by drive, or by the quest to finally feel useful in life. Are his films actually hopeful? He always leaves that for you to decide (quite literally with ambiguous endings in the majority of his films). Keep note that some of this films may not be for you, but I think you can say that all of Aronofsky’s films aren’t for everyone, as he is one of the most provocative filmmakers of our time. Here are all of the films by Darren Aronofsky ranked from worst to best.

8. Noah

While I have Aronofsky’s biblical epic, Noah, ranked last, I am still going to defend it a little bit. I find his angle on the highly familiar story to be quite interesting, particularly because it takes into account how demanding Noah’s quest is, and the backlash one may have received in a world that turned its back on God and will likely refuse to listen to the one person that has a current connection with Him. Noah is depicted as being mentally unstable and that this quest — to bring two of every animal onto an ark to survive the flood that destroys everyone else — is one of delusion. I can see why that would bother some, but I find this fascinating: as if people have been striving to not feel worthless even at the start of time itself. Regardless of whether you believe Noah or not, the film is ambitiously different. Not everything works (the fallen angels looking a little Tolkien in nature are odd, I won’t deny that), but when they do (that montage about the inevitability of humanity’s tendencies for violence and sin), Noah is actually quite remarkable. This is still Aronofsky’s weakest feature, but I wouldn’t dare call it bad.

7. The Fountain

I used to outright dislike The Fountain until I got a little older and wiser. Grasping the concept of death is always going to be nearly impossible: just when you think you’ve accepted it, you’ll find that you only thought that you did. I get that a lot more now, and it helps me understand The Fountain’s ambitious nature. Having said that, this does feel like the biggest misfire of Aronofsky’s career only because you can tell that there wasn’t the budget or means that such a huge picture demanded. I used to let that get to me, because The Fountain does feel only like a portion of something larger and more fulfilled. Now I see it from a different angle: look how much Aronofsky accomplished with so little. With some of the strongest aesthetic and emotional elements in his entire filmography (thanks to the magnificent work of Aronofsky’s pals Matthew Libatique and Clint Mansell, and the tender acting of Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz, who play multiple versions of the same soul), The Fountain is incomplete but still incredibly moving as is. I appreciate it in the same way I do Jai Paul’s Leak 04-13 (Bait Ones): I know they’re far from finished, but what we have is impactful enough.

6. The Whale

The Whale could have been even better (and I am aware that I am of the minority that actually like this film), but it’s a rare time where Aronofsky somewhat oversteps his boundaries as a pusher of buttons, as the film gets so cynical to the point of shaming its characters. Nonetheless, I still find the film to be one of the auteur’s more emotional efforts that got to me personally. Conceptualized and shot during the pandemic, The Whale places us claustrophobically in its lead character’s house for the vast majority of its duration (Matthew Libatique’s limiting aspect ratio also suffocates us, as we feel the walls of the screen close in on us). Everyone in this film experiences self loathing, especially Brendan Fraser’s Charlie (who uses his energy to find the best of others instead), and it is this star’s breathtaking turn that really brings The Whale from being a well-intentioned effort by Aronofsky into a fully realized fable. The Whale does feel like Aronofsky’s most heavy handed effort that gets in its own way occasionally, but I find it powerful and visceral.

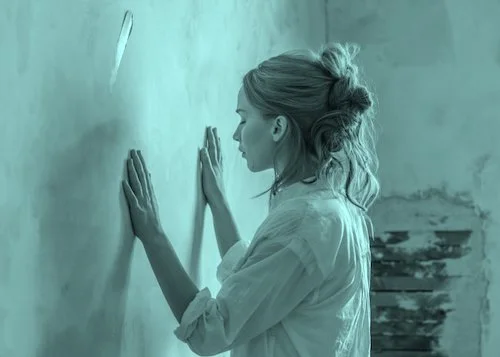

5. mother!

Arguably Aronofsky’s most upsetting film, mother! takes the religious tones of Noah and The Fountain and the blatant tones that you’d later find in The Whale and shoves them in a blender to make a disturbing allegory about the destruction of our planet. While I feel like it is a little too obvious at times, I applaud Aronofsky for going fully arthouse with this one, and it’s actually a side of his I’d like to see more often. In my initial review, I may have been a little harsher on the film than it may deserve, but I still feel as though it tries a teensy bit too hard at getting its environmental and religious points across. Nonetheless, the end result still is extremely unique: a punishing look at a house being built and subsequently torn down whilst the love inside died long before. As time goes on, I appreciate mother! a little bit more and more, and I think those that are the most sickened by it will likely always remain that way (and those that adore it also won’t change). I won’t call mother! his most ambitious film, but it for sure feels like Aronofsky’s biggest risk, and that’s an idea I’ll never get tired of (seeing established filmmakers push themselves and their audiences past their boundaries).

4. π

The film that started it all. π (or Pi) is one hell of a debut by Aronofsky, and easily one of the greatest shoestring budget indies of all time. Already at such a young age Aronofsky was theorizing about death, synchronicities in nature, science, and life, and the potential that being too involved will destroy life for you: knowing too much won’t make anything enjoyable. Should we be blissfully ignorant? π leaves that question up to each and every individual viewer with its titanically bittersweet ending. This also is the first film of Protozoa Pictures which was founded by Aronofsky himself to get this film completed (the company would subsequently be responsible for all of Aronofsky’s features, with him acting as a head producer each time). This was the spark of many great things, in case you couldn’t tell. As a standalone film, π is eerie and jarring, but it gets your mind racing every time you watch it. It is perhaps Aronofsky’s most mentally stimulating film, but it isn’t void of soul as we watch a gifted man succumb to conspiracy, existential dread, and societal panic.

3. Requiem for a Dream

Arguably Aronofsky’s breakthrough picture, Requiem for a Dream remains one of cinema’s most relentlessly punishing works. Unlike a number of its peers (other 90s and early aughts films that played dangerously and were marketed towards young adult cinephiles that like edginess), I think Requiem for a Dream has actually aged better. The bonkers hip hop style editing always places us in areas of uncertainty whilst never wasting a single frame. The visual trickery makes us feel like we are seeing things and losing our own sense of reality. Seeing four different lives collapse via addition is heartbreaking, and Requiem for a Dream isn’t any easier to watch twenty years later. It’s as if we hope for different outcomes each time we view the film, even though that will never happen for these souls that all achieve greatness before falling from grace. If this is the closest Aronofsky ever gets to hyperlink cinema, I’ll take it, because I don’t think any of us can handle his take on, say, Magnolia. It may be far too much to handle. Requiem for a Dream is just the right amount of tragedy: enough to permanently affect you, but not too much to cause you to not care because of hyperbole.

2. Black Swan

Black Swan seems so obvious with its symbols and themes, especially when they get spelled out to us time and time again. I find that there is so much more going on underneath the surface of Black Swan, ranging from the question of how much Nina has imagined for the entirety of the film (and not just its zanier moments) to the note-for-note adaption of Swan Lake for a new millennium (if The Red Shoes by the Archers can get a pass for being quite similar to its source material, the similarly melodramatic Black Swan does as well). I’m also aware of how indebted Black Swan is to Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue (which I consider a masterpiece of animation), but the film also wears all of its aforementioned influences on its sleeves, creating a hodgepodge of artistic perfectionism that leads an entertainer to their darkest hour.

There’s also a self awareness in Black Swan that acknowledges how problematic tales of old can be (where a woman was unfortunately always slated to be an object of desire for men) in this dangerously erotic film. Black Swan is an entire casserole of mania, conflict, and dated notions, all combatting each other so effortlessly in this gorgeous-yet-horrifying portfolio. With so many people at their very best (Natalie Portman as Nina, Libatique, Mansell, and even Aronofsky to a degree), Black Swan could have been a mess if it wasn’t so strong. It’s possibly the only time Aronofsky could get carried away without faltering, and it’s still exhilarating to see.

1. The Wrestler

Aronofsky’s most realistic film, The Wrestler, also happens to be his best. I said Black Swan has his best direction, but from an artistic, showboat angle. The Wrestler has Aronofsky dialling himself back and allowing his strong team to work their magic without the director’s usual marks. Instead, he guides them in this minimalist-yet-raw depiction of a has-been wrestler struggling to survive. Mickey Rourke is a testament to Aronofsky’s ability to bring the best out of his stars, whether it’s those that are contemporaneously established (Portman, Jennifer Lawrence, Ellen Burstyn), those not synonymous with acclaimed acting (Marlon Wayans, Emma Watson), or those that deserved a career resurgence (Fraser, and Rourke, here). Aronofsky is one of the best directors when it comes to letting performers shine and be their very top selves, and you can see that with Rourke’s tender-yet-pugnacious performance that kills my soul every time I see The Wrestler.

The film is the best version of Aronofsky’s quest to find hope within the hopeless, as we root for Rourke’s character Randy to succeed. We can’t help but find how he gets in his own way again and again, but there’s very little here that Aronofsky feels the need to amplify: we get the message loud and clear in a more subtle way. As a result, The Wrestler remains massively emotional and devastating. It acts as a modern day fable of self sabotage during the chase for glory, and it may very well stay as Darren Aronofsky’s magnum opus for years to come. Aronofsky turns his obsession with anthropological analyses onto America time and time again, but here he is at his observational best. We aren’t transported to the setting of another (be it a cluttered apartment, the stage, or an astrological plane). We all find ourselves in Randy: a tabula rasa for all of us that have ever had to fight uphill battles without much success. It is a masterpiece of American cinema, and I don’t think that will change. I feel like its reputation will only grow in time.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.