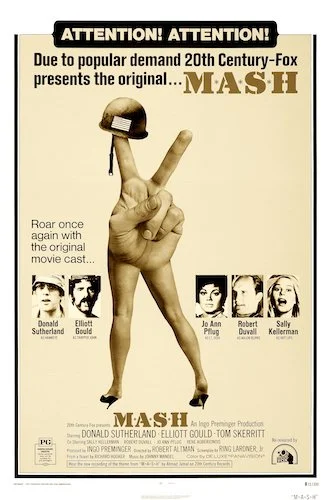

M*A*S*H

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. M*A*S*H won the fifteenth Palme d’Or — temporarily reverted back to the Grand Prix — at the 1970 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Miguel Ángel Asturias.

Jury: Guglielmo Biraghi, Kirk Douglas, Christine Gouze-Rénal, Vojtěch Jasný, Félicien Marceau, Sergey Obraztsov, Karel Reisz, Volker Schlöndorff.

The wonderful and curious thing about the hindsight of accolades is having the knowledge of what came afterward. I don’t think that M*A*S*H has aged in any way outside of what progressed from this breakthrough film. I personally feel like Robert Altman would go on to make even better films, and I also prefer the M*A*S*H television show (not sentiments that everyone will agree with, and that’s okay). So, why the Palme d’Or back in 1970? Because Cannes wouldn’t have known about what would transpire. This was a breakthrough film for Altman that single handedly placed him on the map of noteworthy American auteurs. There certainly wasn’t a show either, because that came after the success of this feature (particularly the attempts to recapture Altman’s satirical tone). As it was, M*A*S*H was a completely unique and fresh film for its time that felt unlike anything else, and you can see why it would have won the Palme d’Or after considering this. We know now about Altman’s signature style and have experienced it in many works since. We grew up with the M*A*S*H TV series and have appreciated its own successes. We weren’t there on that Cannes jury to see the M*A*S*H film for the first time and feel that this was either the spark of something more or one of the most singular films in existence. The latter no longer holds true, given Altman’s filmography and the amount of Altman imitators out there. It certainly could have been true back in 1970.

Ignoring all of this, I’d like to remind that I don’t think M*A*S*H has aged one iota either way. While I like how the series was able to fully embrace the comedic antics of a military medical unit and focus on the darkest elements of war with complete dedication (a sitcom with hundreds of episodes will definitely be more capable of doing so than a feature film), the amalgamation between commentary and silliness that Altman achieves is still commendable. We’re getting a coruscating response to the Vietnam War (although set during the Korean War) amidst a darkly funny look at the “real” goings-on in the battle ground. It’s a strange juxtaposition, and we can feel the absence of life in the wounded or dead because of all of the goofy shenanigans that render us human that parade around them. Altman reanimates the blending of tones from Richard Hooker’s source novel MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors, but he deviates as he felt was necessary. The M*A*S*H TV show would reflect back on a few of Hooker’s original ideas (not symbolizing the Vietnam War specifically, for instnace), but the series would otherwise try to go the distance with what Altman was doing, especially because it felt like unchartered territory back then. Were we ready to guffaw at uncomfortable subject matters? I suppose so if M*A*S*H was incredibly successful and experienced longevity in a multitude of ways. Like a Shakespearean jester, a lot of truths come from when we are caught off guard: during a laughing fit.

M*A*S*H blends genres so effortlessly that this special, satirical tone became a signature trait for Robert Altman.

There isn’t much of a plot in M*A*S*H rather than a premise: the daily lives of army surgeons amidst both the chaoses of war and of society (much of the buffoonery that happens has more to do with the absurdities of fraternity culture, political favouritism, and toxic masculinity rather than war itself). M*A*S*H is purposefully messy, like you’ve been tossed into the deep end to make sense of it all. You just let Altman and his all star cast (another one of the maverick filmmaker’s traits) — including Donald Sutherland, Elliot Gould, Sally Kellerman, Robert Duvall (et cetera) — yank you around to your next peculiar excursion, ranging from serious work duties and past time tomfooleries to the climactic football sequence (which is framed like a tongue-in-cheek traversing of a battlefield in its own way). While we are effectively seeing the majority of characters Hawkeye and Duke’s terms during the war, M*A*S*H itself feels like a day-in-the-life of the field; we’ve just attached ourselves to two of the interesting souls within it.

I’m spoiled when I say that the series feels fuller, but I do feel like the M*A*S*H film is also missing just a teensy bit extra when it comes to the scope of what is going on. I can’t help but bring up another reference point, and that’s Altman’s Nashville which is longer, more complete, and more effective (whilst covering far less severe subject matters, outside of its political and controversial subplots, of course). Even if I had never seen an Altman film outside of M*A*S*H or the series that preceded it, I believe I would still feel like the film went quite far with its tone, statements, and humour, but it could have gone even further with this unusual world that (then) didn’t feel like anything else. Could I have done with another hour to dig deeper into some possible storylines and ideas? You bet! I will always appreciate M*A*S*H for what it is and love it as the seed that would branch out into some of my favourite things of both screens big and small. As it stands on its own, M*A*S*H is biting, strong satire, and is still relevant in many ways. Its stance on war still pertains. Its blending of comedy and tragedy still holds up with many of the shows and films we consume today. It was extremely ahead of its time, and Cannes picked up on that instantly.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.