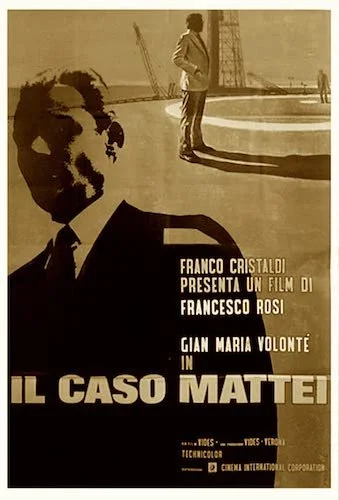

The Mattei Affair

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. The Mattei Affair won the seventeenth Palme d’Or — temporarily reverted back to the Grand Prix — at the 1972 festival, which it shared with The Working Class Goes to Heaven.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Joseph Losey.

Jury: Bibi Andersson, Georges Auric, Erskine Caldwell, Mark Donskoi, Miloš Forman, Giorgio Papi, Jean Rochereau, Alain Tanner, Naoki Togawa.

Out of all of the ties that occurred with the Palme d’Or prize at Cannes, the one that happened during the 1972 edition feels the most understandable. This wasn’t a tough call between two drastically different films like Kagemusha and All That Jazz, for instance. The 1972 festival boasted two Italian films that featured political subject matters with a feature character that has to face a difficult system with their back against the wall, and both of these characters are played by Gian Maria Volonté. It almost feels like pure coincidence: which of these similar films would take the grand prize? Why not both? In this first film, The Mattei Affair, Volonté portrays the real businessman named Enrico Mattei that tragically passed via an airplane accident just moments before he was due to land. Director Francesco Rosi then studies this unusual circumstance, only to discover some hideous truths that were kept from the public (or so states the film). Here is a conspiracy theory that Rosi wanted us to know, and it won’t likely sit well with you.

The film is told in a metaphysically docudrama way: like a filmic essay with the exact footage that Rosi requested, ranging from what he would need to shoot to what he could already find. This is also where the whole tied-award thing comes into play: personal preference. The other film that won in 1972 is The Working Class Goes to Heaven, which is more of an underdog, blue collared tale (with some heavy moments, for sure), but The Mattei Affair feels like a more harrowing film with far less faith that anything will actually be done about these portrayed injustices. Which jury members were more pessimistic about how things would turn out? The Mattei Affair is the kind of political film that isn’t necessarily promoting change (although it existing does beg the question as to why we aren’t doing anything to promote complete transparency within our society), but it does place you in a bothered mindset as to maybe encourage you yourself to take action. Whether you like the film or not, it feels next to impossible to not feel at least a little bothered during The Mattei Affair: if this is true, how did we as a civilization get to this point? If it is false but still stemming from real occurrences, why are we even this close to a world where the pursuance of progress is stunted by greed-driven assassinations (or, in this case, allegedly)?

The Mattei Affair is a thought provoking experience that causes you to question everything you see in the film (and everything afterwards, with the hopes that you will be less mindlessly driven).

It’s not all speculation, however. The successes, transformations, and avocations of Enrico Mattei are displayed at large throughout this film, as to build up his prominence within the oil industry (with his focus not on money but on power) and within various other industries. The film doesn’t portray Mattei as a perfect man but as a highly interesting magnate whilst the modern conventions of society ooze around him with heavy corrosion. There will be corruption everywhere, and it’s a sad fact we’ve all just had to accept. Those that strive for power likely have to answer to those with more power than them that are already established. That’s what Rico seems to be getting at with The Mattei Affair: an honest question surrounding a mysterious death asked with pent up frustration. I can’t help but think of films that have treaded similar grounds a little more sharply and with more audacious gall like Z or Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (the latter stars, once again, one Gian Maria Volonté [he was clearly on a roll]), especially since these films came before The Mattei Affair. Still, there’s enough urgency and relevancy in this feature that still holds up, and its hodge-podge nature makes for a frantic, unsettling viewing (which is quite appropriate, if I do say so myself).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.