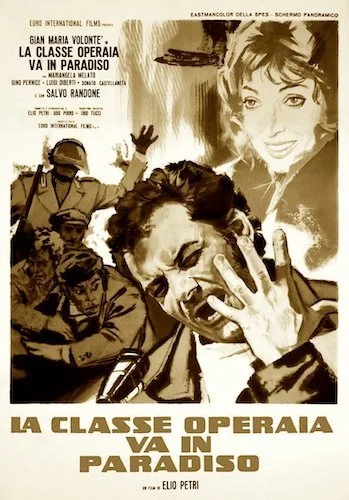

The Working Class Goes to Heaven

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. The Working Class Goes to Heaven won the seventeenth Palme d’Or — temporarily reverted back to the Grand Prix — at the 1972 festival, which it shared with The Mattei Affair.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Joseph Losey.

Jury: Bibi Andersson, Georges Auric, Erskine Caldwell, Mark Donskoi, Miloš Forman, Giorgio Papi, Jean Rochereau, Alain Tanner, Naoki Togawa.

Who doesn’t love a good underdog story? Well, what about one where the protagonist discovers far more than they bargained for? Chinatown? Network? Here’s another example of this sort of sore revelation: The Working Class Goes to Heaven. In this blue collared work drama, a dedicated labourer (Lulù) becomes the face of a movement for better employment rights, work conditions, and treatment. Well, this comes after we get a bit of a different perspective of Lulù: a man of the system that (seemingly) takes charge in any way he sees fit. This is until he faces a serious work related injury: the decimation of an entire finger within a machine because of the speed of his labour. This 180 renders him a man against that of which he once championed, and it is through this change that he actually discovers more about the industry he once justified. In fact, he was used as the poster boy of his company to belittle the inferior work of others, as he was so dedicated to his job. That same face would then lead the rebellion.

There is a lot of tension and uncertainty throughout The Working Class Goes to Heaven, so it isn’t quite your typical story about the overcoming of tribulations. It also isn’t as negative as the aforementioned New Hollywood classics I brought up before, as there is a bit more faith in Lulù and what he can maybe accomplish with his movement. We have Ennio Morricone working his musical magic to make us feel uneasy (his brooding score occasionally reads like a racing heartbeat or a sickening patter of a weakened pulse), and director Elio Petri’s interesting tones to keep us flustered. There’s also Lulù having to answer to his imperfections: his seemingly “perfect” life wasn’t lived as such, and he now has comeuppance to bite him in the ass when everything else comes crashing down. It’s an interesting element to the film, because it shows that we run our own lives as poorly and as haphazardly as the companies we work for: a perspective that isn’t tackled nearly enough in such a story.

While a film that champions the underdog, The Working Class Goes to Heaven still isn’t all bells and whistles.

The Working Class Goes to Heaven also dips into the hysteria of society surrounding these labour based movements and the struggling working class (something Cannes, surprisingly, rewards a lot, including I, Daniel Blake, Rosetta, Pelle the Conqueror, Marty, and many more). I feel like The Working Class Goes to Heaven goes beyond its premise to truly exhaust all of the separate moving parts of this kind of predicament, ranging from the worker himself, his personal life, his career as it appears to him, how his career is actually going, life after change, and his drive being a catalyst for many others to reevaluate themselves. There’s a pinch of cynicism within the film, but there’s just as much hope in the film’s core as well. It’s a nice balance to have with such a subject matter: enough bleakness to recognize the woes of partaking in such an uphill battle, but the faith to keep us going and not feeling hopeless. The Working Class Goes to Heaven seems to be stuck in the halls of time, but I would give it a watch. It still pertains to many of our lives today, and I feel like its tonal balancing act is indicative of how many of our dramas are made today.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.