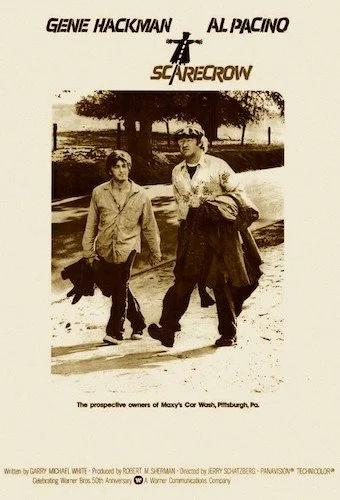

Scarecrow

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Scarecrow won the eighteenth Palme d’Or — temporarily reverted back to the Grand Prix — at the 1973 festival, which it shared with The Hireling.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Ingrid Bergman.

Jury: Jean Delannoy, Lawrence Durrell, Rodolfo Echeverría, Bolesław Michałek, François Nourissier, Leo Pestelli, Sydney Pollack, Robert Rozhdestvensky.

Considering that we still have cinephiles that are obsessed with New Hollywood and the actors at the forefront of this film (a newly-Academy-christened Gene Hackman, and a young talent named Al Pacino who was on the rise with The Godfather), I am quite confused as to why Jerry Schatzberg’s Scarecrow isn’t talked about more. This is as bare bones New Hollywood as cinema gets, as if this was a sister film to Midnight Cowboy (and there are definitely a number of similarities between the two films, including two male misfits facing the shifting times of America together at the very bottom of the lower class). In Scarecrow, Max (Hackman) and Lion (Pacino) are homeless and traversing across the states; they dream of a potential way out of their predicament, particularly through a success story that seems instantly unlikely for us audience members (but how can we dismiss unfortunate spirits that want to turn new leaves?).

Each traveler has a different ambition. Max wants to pick up the money he has been stockpiling over in Pittsburgh. Lion is estranged from his former wife who is taking care of their child (of whom he has never met); he too has been sending his money to a location, and it happens to be this family he is distanced from. Unlike the highly unlikeable outcasts of Midnight Cowboy, the leads in Scarecrow at least seem like gruff individualists that could be redeemable. Seeing life toss them around again and again is rough, particularly when it leads to the protagonists cracking in various ways (especially Lion’s climactic detonation that broke me when I first saw it). Schatzberg is the kind of filmmaker that won’t lie to you about fair shakes; he acknowledges that many of us suffer when we chase the American dream. No matter what part of the country we are in at any point in Scarecrow, we see empty promises, exploiters preying upon the wide-eyed and vulnerable, and disappointment after disappointment.

Scarecrow boasts two brilliant performances from Al Pacino and Gene Hackman.

We grip onto every scenario and word because of Hackman and Pacino, who deliver two of the best performances of their respective careers (if you are fans of either, I would highly recommend seeing this film, as you may find work that could place in your top five favourites of both). Hackman is short-fused and difficult, but you can sense a heart underneath the roughened exterior. Pacino feels naive until enough misfortunes bring him to the brink of desperation. Together, you’ll find a spectrum of jadedness, and you can’t get more New Hollywood than this; not once do you feel like things are going to be sugar coated or that there will be a good ending around the corner. It’s purely downhill from the start, but you can’t help but root in support. Scarecrow is a simple film but a strong character study within an even stronger allegory, because life doesn’t run on narratives: we face whatever comes our way, and so do Max and Lion.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.