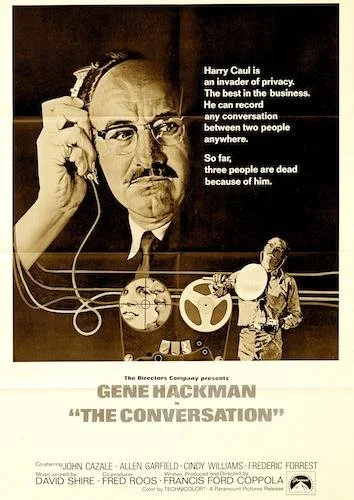

The Conversation

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. The Conversation won the nineteenth Palme d’Or — temporarily reverted back to the Grand Prix — at the 1974 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: René Clair.

Jury: Jean-Loup Dabadie, Kenne Fant, Félix Labisse, Irwin Shaw, Michel Soutter, Monica Vitti, Alexander Walker, Rostislav Yurenev.

The four-film streak of perfection within Francis Ford Coppola’s career is quite fascinating: enough so that he could make literally any other film and he would still be considered amongst the greatest directors of all time (hell, he made Jack and got away with it). Let’s have a look at them, shall we? The Godfather was a gangster film made by an underground art fiend that somehow translated nicely for the mainstream audiences of the world (enough so that it actually helped change cinema for good); it came at exactly the right time during the New Hollywood era. Its sequel, The Godfather Part II, is an even better film (in my opinion) that revolutionized what a followup film could be (as a sequel, a prequel, or, in the case of this film, both storylines fused beautifully together); at this rate, it looked like Coppola was now a member of the then-contemporary class of trendsetters, and he understood how to keep intentionally shifting mainstream cinema. Then came Apocalypse Now, which was his attempt at an action-war film (his artistic roots would luckily get in the way, resulting in one of the finest epics ever made); that film would go on to win the Palme d’Or.

But so did The Conversation: the smallest film of the four, released quietly during the same year as The Godfather Part II, and still his least-discussed masterpiece. Consider it his Beggars Banquet, if we were to reflect on his filmography as if he were The Rolling Stones (and the streaks-of-four make that comparison worthwhile). Is it weaker than the other three films? Sure, but it’s still The Conversation, so it is only slightly inferior. If any other New Hollywood director made The Conversation, it would be crowned as their masterpiece and discussed ad nauseam until the end of time. There’s one additional element that makes this film worthy of investing in nowadays: its relevancy. I can’t profess that it is his most significant film today, since both Godfather films feel important (culturally, cinematically, and even its depictions of systemic corruption, changes-of-heart under the weight of power, societal greed, and family values), and Apocalypse Now is similarly as unrivalled (it is a singular war film epic, but its statements on how war breaks us sadly still pertain to today’s world). However, The Conversation still has a lot to say that directly affects the majority of you readers, internet surfers, and citizens of the technological age.

The Conversation starts off as an intriguing look at the art of surveillance, before delving into the paranoid thriller that it secretly was all along.

While a film that targets the war on privacy back during the 70s (and within the context of a surveillance aficionado), The Conversation still regards what we face with our devices that pay attention to our every word, camera angle, and search result. This paranoia felt by an opened can of worms (that our private lives really aren’t so private) is certainly a common phenomenon today, especially considering Edward Snowden’s whistleblowing on the National Security Agency back in 2013. What The Conversation pulls off instead is a warning via a fictional motion picture, but the caution is all the same: an alert that we are not in control of our own footprint. Similarly, The Conversation goes down its rabbit hole via someone that’s in the know: Harry Caul (played by Gene Hackman), who is an expert when it comes to the art of spying, and so he picks up on signs that most people would overlook. He is the go-to source for others when it comes to surveillance, but he winds up being the most damned member of society; it’s as if his art turned in on him because he became too experienced and aware.

As we see Caul get pursued, The Conversation reveals its best cards. It’s spooky enough seeing what we’re capable of with this sort of technology (recording devices, particularly), but to know that the best in his field has less control over his own privacy than the rest of us is damn well frightening (again, we can easily refer to Snowden as a real life contemporary similarity). We get caught off guard with being fascinated by the technicalities within surveillance during the first act, but Hackman’s Caul is brilliant: his coldness and unflinching nature represent a tired soul that isn’t impressed by that of which he already knows, so we can sense an uneasiness from the very start. As The Conversation gets more and more frantic, Coppola leaves his most sadistic twist for last: permanence. We get zero closure, but we also shouldn’t for a film of this nature. What closure is there to even look forward to? If the truth is that we aren’t sure of how much we are truly being spied on, then The Conversation ends exactly as it needs to: uncertainty. How’s that for a horrifying final say that will likely stay with you forever?

The Conversation self destructs to the point of nothingness, and it’s highly effective.

What began as a study turns into a project of self destruction, and Caul’s mind detonates like any of ours would. What has been familiar for the first hour and a half begins to be torn apart (structurally, narratively, metaphorically, and even literally, in some cases), and stripping everything away to get some comfort doesn’t work. It’s a sick trick that gets pulled on us, but it’s an essential one. Have you considered the title of the film? What conversation is there, really? The one Coppola has with us about an unsettling subject matter? What Caul has with himself as he lives an isolated lifestyle? What Caul has with those that are spying on him (this is still quite one-sided, wouldn’t you say)? If it’s the latter, consider the upper hands at play: Caul can respond but not be heard (he isn’t having an active dialogue, anyway). He can hear what is told to him, but he has zero idea as to what is going on behind the very walls he tries to tear down (to no avail). This is an inconvenient conversation in every sense, but Coppola’s discussion with us is an absolute must.

This claustrophobic, minimalist thriller feels like an indie film through and through, and it is even timeless in this respect (I can think of a number of contemporary films that operate quite similarly in terms of spacial relation, like Ex Machina or Primer). There’s a huge thesis topic told as small as possible, in a way that is quite impressionable, really; this is a sight to see regarding a director like Coppola that adored being a large scaled storyteller (lest we forget the production catastrophes of Apocalypse Now). This is a thriller that gets under your skin, infests in your mind, and is unforgettable both artistically and thematically. It’s Coppola at his most restrained during his prime, and it is an essential watch for fans of his, thrillers, political films, or any believer of the motion picture experience. As much as both Godfather films are talked about (and hopefully certainly more than The Godfather Part III) should The Conversation be championed. If anything, this could secretly wind up being your favourite Coppola film and you wouldn’t even know it until you see it.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.