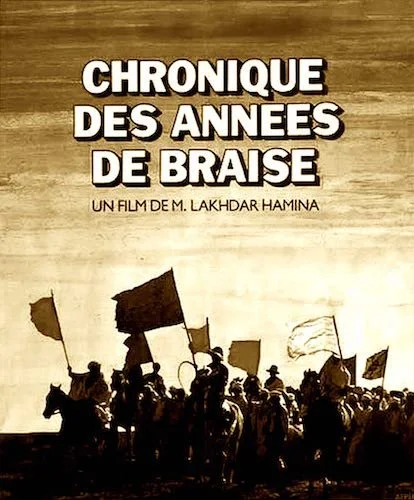

Chronicle of the Years of Fire

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Chronicle of the Years of Fire won the twentieth Palme d’Or (which the award would again be known as from this point onwards) at the 1975 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Jeanne Moreau.

Jury: André Delvaux, Anthony Burgess, Fernando Rey, George Roy Hill, Gérard Ducaux-Rupp, Léa Massari, Pierre Mazars, Pierre Salinger, Youlia Solntzeva.

As long as an ambitious film is made with the barest of competence, it will likely be commendable to some degree. I say that regarding Chronicle of the Years of Fire not because it is poorly calculated, but because it is a forgotten epic, and so I begin this review with the mindset that lovers of large-scaled cinema would likely get something out of this passionate, political drama. Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina is a highly revered figure within Arabic cinema, and knowing that this is one of his finest projects should already be a selling point. It may be a bit overlong, sure, but Chronicle of the Years of Fire is told with the utmost visceral determination, with Lakhdar-Hamina wanting to be heard as clearly as possible. The Cannes jury were listening attentively, with this film being selected as the festival’s big winner over some major projects like The Passenger, A Touch of Zen, and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (although Martin Scorsese wouldn’t need to wait very long for his turn with the Palme d’Or).

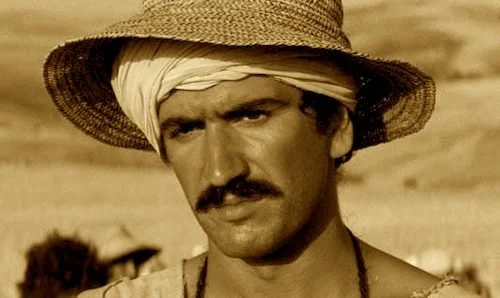

Chronicle of the Years of Fire tells a thorough tale about the entirety of the Algerian War of Independence, and so there have obviously been comparisons between this film and The Battle of Algiers (one of my all time favourite films). I will try to refrain from committing to the same analysis, outside of pointing out that the latter is a more intimate film told with more focal points, and Chronicle is a massive story through one major perspective: Ahmned (a poor individual that can see the colonial takeover and the rise of the revolution happen right before him). It feels larger as a result (although the three hour runtime would help with that too), and all of the goings-on with a sole vantage point can feel overwhelming. Chronicle doesn’t say as much as it may want to, but it definitely transports you to the place that Lakhdar-Hamina wants you to be: within it all. You can’t ignore what you’re surrounded by, and that’s where Chronicle succeeds the most. It’s undeniably harrowing.

Chronicle of the Years of Fire is a motivated epic that succeeds with placing you amidst the turmoil of the Algerian War of Independence.

What Chronicle has with immediacy it lacks in staying power, outside of being hard to shake off and its lessons never leaving you. As a statement, it is resilient. As a film, however, it feels fine to experience once and maybe never again, and it has less to do with how difficult it is to watch and more to do with its artistic resonance (or slight lack thereof). However, it still feels important to see once as a slice of history and as a titanic film that at least can be felt whilst watching. It’s this kind of urgency that wins panel awards right there and then. I also don’t think Lakhdar-Hamina was interested in the reception of his film outside of how much you learn, feel, and understand what millions of people went through, and with this in mind Chronicle of the Years of Fire works quite well. It’s a great starting point if you are interested in seeing noteworthy Algerian cinema (or Arabic cinema as a whole, even), and worth a try if you love epics of the political variety.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.