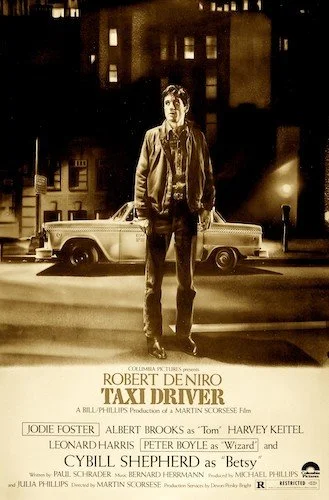

Taxi Driver

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Taxi Driver won the twenty first Palme d’Or at the 1976 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Tennessee Williams.

Jury: Jean Carzou, Mario Cecchi Gori, Costa-Gavras, András Kovács, Lorenzo López Sancho, Charlotte Rampling, Georges Schehadé, Mario Vargas Llosa.

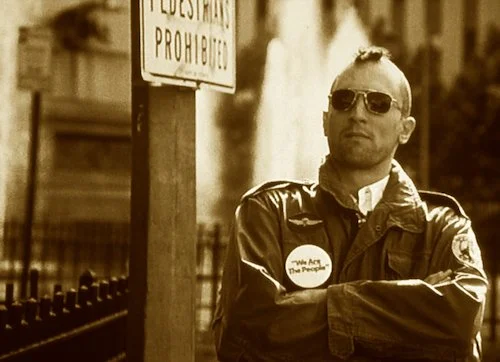

I’ve covered Taxi Driver before on Films Fatale (because why wouldn’t I have reviewed it by now?), so I want to use this Palme d’Or project review to discuss the potential reasons as to why it won. The film remains as controversial as ever, especially with the rise of news stories surrounding awful people that go on bullshit missions to further destroy the world when they insist that they’re helping. Travis Bickle is one of cinema’s finest antiheroes because of how deluded he is (and how much the film is torn between being his dream — with its hazy feel and broken feeling — and a neutral capturing of a psychopath’s devolution). It’s easy to see why many awards ceremonies would stay quite clear of accolading such a film that could make such an honour feel like the justification of awfulness, but Cannes and its juries are smarter than that. They understand how context works, and Taxi Driver isn’t about getting us to feel sorry for someone that effectively becomes a terrorist. It’s a complex character study that takes into account many of society’s flaws. Bickle is worse than all of these oversights, but Taxi Driver is able to highlight them nonetheless.

I don’t really single out the Cannes jury in these reviews, but knowing who possibly selected Taxi Driver (it wasn’t an unanimous win) makes this analysis all the more fascinating. The jury head is one Tennessee Williams, who has captured ugly sides of America time and time again. There’s also Costa-Gavras: a master auteur capturer of political atrocities. Charlotte Rampling — an early champion of difficult films as a coveted thespian — is on this jury, too. These are all people who understand why something like Taxi Driver is an important film as a societal statement, but an even stronger piece of American art. The big misconception many contemporary watchers have with Martin Scorsese is that he is a director that indulges in violence and crassness as his signature style. He has a number of films that contradict this: The Age of Innocence, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Hugo, Kundun, and more. He happens to have films that deal with crime, but he also is a student of art films as well (he has commented on his love of films like The River, The Red Shoes, and The Horse Thief many times before), and you can definitely view Taxi Driver (or any of his crime films) more through this lens than one that focuses on being a source of dangerous entertainment.

As dangerous as Taxi Driver is, its artistic angle is what renders it effective, not its shock value.

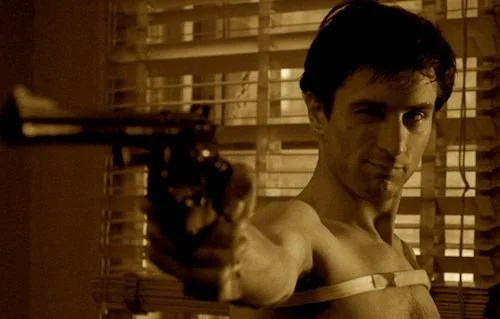

Bickle is a Vietnam war veteran suffering from post traumatic stress disorder, who cannot sleep at nights and also doesn’t really have much to live for; he tries to fix both problems by becoming a taxi driver during the graveyard shifts. He comes into contact with the rough streets of New York City, and his pent up angst churns into disgust. He soon makes nauseating observations about the people of New York, which may have started from a well intended place (wanting to stop sex trafficking, particularly involving children) but then it slides down into awful forms of intolerance (racism, for starters). Bickle is not well, but he is a vigilante in his mind. He lives alone and doesn’t have anyone to tell him what he is doing is wrong. He finally begins to confront people around him: his love interest Betsy, who doesn’t share his sentiments; Senator Palantine, who Bickle completely misreads; his cabby pals who do care (especially “Wizard”) that maybe don’t know Bickle quite as well as they should.

That’s all futile and it only hurts Bickle’s toxic quest to cleanse America, and this all boils down to the final act of the century: a bloodbath of misguided proportions. There’s even a “Hollywood” ending, but it is quite tongue-in-cheek and quite possibly a fever dream (although Scorsese and screenwriter Paul Schrader are quick to deny this). Whether you treat Taxi Driver literally or not, you’ll find a deeply tortured psyche of someone who is too far gone and irreparable, and that’s what Taxi Driver is all about: introducing us to the kinds of people that films love to pretend don’t exist. The film doesn’t try to justify his existence or what he does, but it just shows that he is very much here. Hollywood has done a good job sugar coating the entirety of the nation for decades. New Hollywood was here to negate this idea. There are very real problems and concerns that could be focused on before we drift off to la la land.

The final act in Taxi Driver is one of the strongest sequences in film history.

Cannes saw the poignancy within the revulsion. This was a true rebellion of American cinema that was built up over the course of many decades. Numerous films came before Taxi Driver within the New Hollywood movement (particularly Bonnie and Clyde, The French Connection, The Graduate, and both Godfather films), but this feels like one of the most shining examples of said era. This is as direct of a rebellion against the glitz and glamour of Hollywood as anything else before or after it, but it’s all for a different reason: spotlighting an unreliable narrator of a protagonist. Not everyone we come across is going to be dandy. Sometimes we do come across people like Travis Bickle, and Taxi Driver gave him his own film. There’s no concrete answer as to what we are looking at, nor are we told to feel any specific way about this central character. We’re just caught within the mess of it all, and it’s quite a daring film (that’s the difference between a film like Taxi Driver and many shock films it may have been compared to at the time). To this day, I feel like everyone has their own thematic takeaways from this film, but we all share the disgust and tidal wave of anxiety that the film elicits. So did the Cannes jury: a film with such a visceral, communal response from everyone could only be a Palme d’Or winner.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.