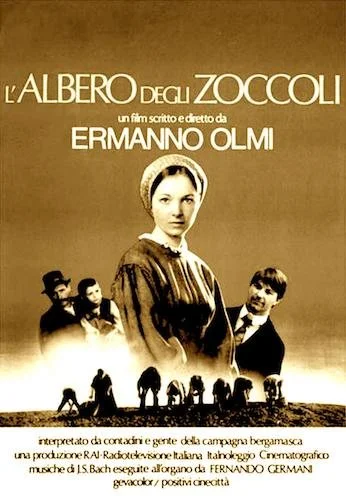

The Tree of Wooden Clogs

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. The Tree of Wooden Clogs won the twenty third Palme d’Or at the 1978 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Alan J. Pakula.

Jury: Franco Brusati, François Chalais, Michel Ciment, Claude Goretta, Andrei Konchalovsky, Harry Saltzman, Liv Ullmann, Georges Wakhévitch.

Director Ermanno Olmi passed away in May of 2018, and film publications all around the world wept. Those readers who weren’t sure of who this filmmaker was were then introduced to The Tree of Wooden Clogs: an arthouse masterpiece that feels like a hidden secret of 70s cinema. What made it particularly fitting to bring up (beyond being Olmi’s opus that cinephiles wanted to pay tribute to, of course) was its depictions of the human experience and the inevitability of all things coming to an end. It’s a bitter truth to accept at the end of this over-three-hour picture, but that’s how it feels with life as well: it hurts even more knowing all that preceded this sudden finale. Film lovers celebrated The Tree of Wooden Clogs in Olmi’s memory, but it was also likely the easiest way they could cope with the surprising passing of a legendary director who deserved more love throughout his career.

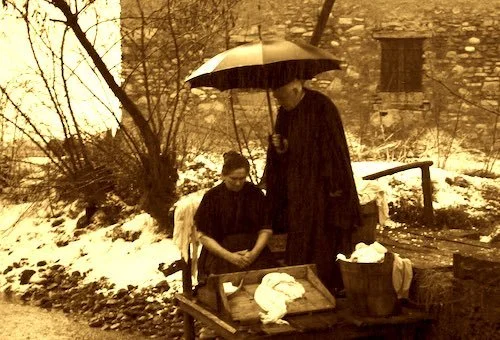

Luckily there was The Tree of Wooden Clogs which won the Palme d’Or and was easily his biggest success. It would cement his legacy for generations, although it remains under-seen. Its importance is felt instantly: like a love letter to both the films of Vittorio De Sica and the region of Lombardy, Italy. It’s also strange to see a neorealist film (or at least an offspring of the movement) in colour, even though Olmi’s film is drenched in mossy greens, deep navy blues, and enough shadows to cast a dismal essence. This is Lombardy as Olmi sees it: a dead end of perseverance. As society evolves beyond the province of Bergamo, we see that life is passing these workers and their families by. We truly feel transported. We’re no longer home when watching The Tree of Wooden Clogs. These three hours are Olmi’s to place you in a world you’ve never felt before (and will likely never experience again, unless you rewatch The Tree of Wooden Clogs).

The Tree of Wooden Clogs casts a magnificently ambitious depiction of rural life during the turn of historical events.

All of the performers here are actual Lombardian citizens and not actors by any means, so Olmi was able to pick up where the previous neorealists left off: finding the truth within those that have lived it. Any professionals would have made The Tree of Wooden Clogs a hammy, melodramatic experience, rather than an enveloping documentation of the turn of the century; while the cast wasn’t then-presently living in the 1890s, they were able to still replicate what was felt during this time. For the majority of The Tree of Wooden Clogs’ duration, we are viewing habitual means and peasantry life take place. This all makes for breathtaking cinema (as patiently told as it may be), and I personally felt completely under the spell of Olmi’s vision: it’s an almost languid affair, as if we are either fully present, or that we feel the stillness of Lombardy while the rest of Italy seemed to be gunning towards the future.

The title of the film is interesting, because the titular tree is only a small portion of the narrative (a story which, mind you, is less to do with a carefully laid-out plot than it does the examination of characters, setting, and responses), but it arrives at just the right time. The tree becomes a symbol of what we’ve seen before: the gestation and growth of a community, with its branches being its families that extend from it. What seems to be a film that exists without telling us too much in terms of a narrative then becomes a build up towards one single act, and I truly felt like I was an inhabitant watching this unfold from my own window. The act surrounds what seems to be a necessity: the requirement of proper footwear in order for the village youths, but the generations of old don’t agree with this progress. What would you have done in this instance? Would you preserve something that could be used beneficially even if it resulted in your potential loss? What separates the use of a tree for shoes from the murdering of a cow for sustenance? When survival is your primary focus, do we even have room to point fingers and blame? We don’t really get to answer any of these questions by the end of The Tree of Wooden Clogs. Exile happens as quickly as death, and you likely won’t be able to prepare for it.

You get many observations of life in Lombardy in The Tree of Wooden Clogs, and all of them are told hypnotically.

Italian neorealism is often brought up with the key favourites in mind (Bicycle Thieves, Rome, Open City, La Strada, Bitter Rice, and the like), particularly by Film 101 classes, but then the movement gets dropped like a hot potato. Why not look at what was directly influenced by it? You’ll stumble upon something like The Tree of Wooden Clogs: a time capsule that feels as necessary to watch as the previously mentioned classics. It’s difficult to understand how such a cold film could feel this rapturous, but this is no ordinary film. You’ll be seated in a village frozen in time, invited to partake in daily rituals and goings-on, and then forced to question your place within it all, what transpires, and what this all means for this community. Ermanno Olmi gets you comfortable and invested in The Tree of Wooden Clogs before he unveils the epicentral dilemma: where do you stand when it comes to a major choice made in the name of that which is desideratum for better living? The Tree of Wooden Clogs is incredibly special. I implore you not to miss out on this gorgeously tragic, slice-of-life, cinematic paragon.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.