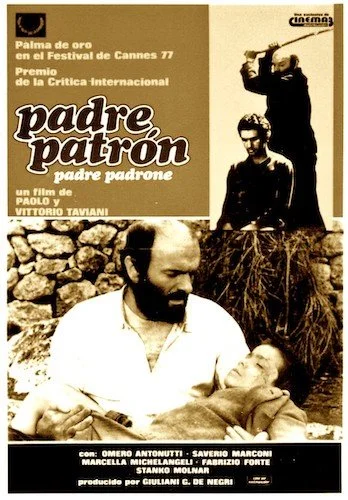

Padre Padrone

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Padre Padrone won the twenty second Palme d’Or at the 1977 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Roberto Rossellini.

Jury: N’Sougan Agblemagnon, Anatole Dauman, Jacques Demy, Carlos Fuentes, Benoîte Groult, Pauline Kael, Marthe Keller, Yuri Ozerov.

Coming-of-age films are generally fanciful and endearing, but not enough of these works really get into the nitty-gritty of the awkwardness of these times of our lives. Enter Padre Padrone: an example of what this may look like. Based on the autobiographical story by Gavino Ledda (who wrote about his upbringing under his shepherd father in Sardinia), Padre Padrone showcases the hideous revelations of boyhood, the real world, and what a young Gavino will have to face once he is ready to brace his mature years alone. It’s interesting to see this unfold, because this is clearly an adult Gavino warning his younger self, and the Taviani brothers capture this tenderness in their film. Wouldn’t you want to nurture and protect yourself from many years ago, knowing what you know now as a jaded adult?

There is also the featuring of so many uncomfortable moments; how abusive Gavino’s father is; the perversions of boys within their journeys of self discovery; some rather unspeakable stuff (believe me, you don’t want to know unless you actually wish to watch the film). I can’t help but think of Jean-Claude Lauzon’s swan song, arthouse masterpiece Léolo when I was watching Padre Padrone, but the former is based in fantasy and the latter reality. I can’t ask Padre Padrone to go the extra mile, because a majority of Léolo is rooted in fiction, but Lauzon’s film truly perfects the disgusting discomfort of being a tween and having a very particulate view of the world. Padre Padrone has some of the same kinds of absurdities, but you don’t feel the mutual connection: that “I can’t believe we were this gross and weird” realization. Instead, you watch Padre Padrone from a distance, and you’ll likely feel judgemental with some of what you see. Léolo forces you to recognize what you once felt when you came of age. You don’t get that with Padre Padrone.

It can feel easy to be repulsed and shocked by what goes on in Padre Padrone.

There’s still Gavino’s personal touches that make Padre Padrone worth watching, particularly the focuses on what would help his cinematic self get out of Sardinia and become the best version of himself. Unlike Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy where the titular character leaves home to have better opportunities and extend what his family is capable of, Gavino vows to leave in Padre Padrone to save himself, and it’s quite sad — yet assuring — to see the extents he goes to make sure he will have a better life (not under his abusive father’s reign). In case it wasn’t obvious, I was constantly reminded of better coming-of-age films whilst watching Padre Padrone, but it doesn’t make it a bad film just because I didn’t find it quite as impactful as the aforementioned works. There’s still this candidness to the film, even amidst all of the bizarre vulnerability, that may have resonated with the Cannes jury back in the 70s, and you can still feel this today; no other films (as better as they may be) can take that away from Padre Padrone.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.