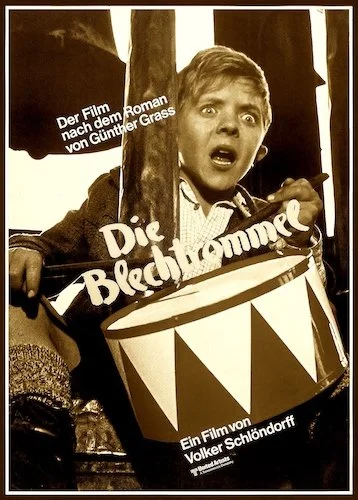

The Tin Drum

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. The Tin Drum won the twenty fourth Palme d’Or at the 1979 festival, which it shared with Apocalypse Now.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Françoise Sagan.

Jury: Sergio Amidei, Rodolphe-Maurice Arlaud, Luis Garcia Berlanga, Maurice Bessy, Paul Claudon, Jules Dassin, Zsolt Kézdi-Kovács, Robert Rozhdestvensky, Susannah York.

The 1979 Palme d'Or is shared by two war films with somewhat divided results. Apocalypse Now didn’t sell as much as it should have but now is considered a war masterpiece (as it should be). Then there’s Volker Schlöndorff's The Tin Drum: a puzzlingly peculiar dark comedy that is childlike in nature but most certainly not for kids. It follows the same stream of logic as films like Matilda, Amélie, The Shape of Water and the like: a youthful innocence captured within the jaded. The Tin Drum predates all of these films and is considerably ahead of its time in this way, as it dazzles its whimsy within the darkest of scenarios, but this doesn’t necessarily mean that it does this the best. This is a strange film that I am equal parts intrigued and bothered by. It is so of its own world that it’s easy to see why first time viewers on the Cannes jury would be wowed back in the late 70s, but it’s not quite as effective today when we’ve seen similar films done with more precision.

We meet young Oskar: a human permanently trapped within a child’s body who can break fragile objects upon command via shrieking, and whom displays his malcontent via the playing of his prized, titular tin drum (who also experiences the horrors of The Holocaust first hand). If this doesn’t sound like it is up your alley, then you will likely be a part of the viewership that can’t stand this film. There are also fans of The Tin Drum that are dazzled by its ability to find that innocence we all felt early on in life, and place it amidst both fantastical and horrific circumstances. I understand that the film achieves this, but I also don’t have to love the ways it does so. One or two shrieks to break glass? Sure. Go for it. Many throughout three hours? We get it by now. Every time Oskar revs up to show someone else his talent, I instinctively got bothered to a Pavlovian degree; luckily I don’t hear shrieking like this often outside of The Tin Drum, otherwise I would be wincing a lot as a reflex. This is not a slight towards David Bennent, the actor who played the young Oskar. I think Bennent does the best he can in his role, especially when he is at his most attentive; you can read a myriad of expressions and thoughts in his eyes alone. The character itself and the need to shriek and slam a drum is one open to being quite irritating. Don’t blame the actor: blame the role.

The Tin Drum is an acquired taste of a film, and the only way to know is to watch and find out. Or you may be as perplexed as I am.

Despite this annoyance and others like it), I still found The Tin Drum to be an interesting experiment that I wouldn’t think many directors would have even dared to attempt (this predates Life is Beautiful, for instance); there’s always The Great Dictator, but that was also doing something much more profound and bold for its time (right in the Nazi party’s face). I acknowledge The Tin Drum’s blending of storybook naivety with historical terror, but also find it unrefined to the point that I’ll likely never love the film as much as I understand it. It’s too long (even two hours and twenty minutes would be excusable), problematic (the circus sequences haven’t aged well, and the sex scenes involving Oskar could never have been appropriate), and it is occasionally too imaginative to be legible as a commentary on war, the loss of youth, or even as revisionist history. Still, I appreciate The Tin Drum for even trying for the sequences that work really well. I may be complaining, but I definitely was under The Tin Drum’s spell here and there. You may love the entire film. You may despise the whole project. You may be on the fence like me. Them’s the breaks with a film like The Tin Drum that is easily one of film’s most polarizing pictures.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.