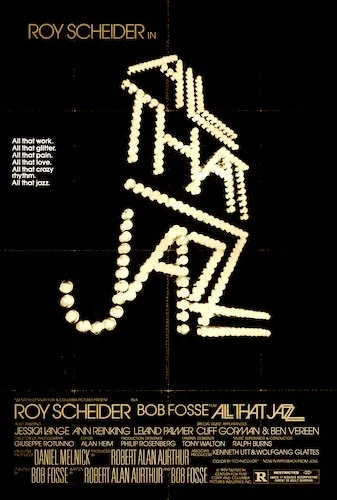

All That Jazz

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. All That Jazz won the twenty fifth Palme d’Or at the 1980 festival, which it shared with Kagemusha.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Kirk Douglas.

Jury: Ken Adam, Robert Benayoun, Veljko Bulajić, Leslie Caron, Charles Champlin, André Delvaux, Gian Luigi Rondi, Michael Spencer, Albina du Boisrouvray.

During the New Hollywood movement, American filmmaking was daring to go where it wasn’t allowed to since the Pre-Code days: completely unhinged filmmaking. What would a movie musical look like during this time? Bob Fosse would know, as he made a few of them. Even people who absolutely despise your typical musicals find something of value in Fosse’s classics, and Cabaret was the winningest film to not win for Best Picture at the Academy Awards (Fosse himself actually won Best Director over Francis Ford Coppola for Thre Godfather. Yes. This happened.). His deconstruction of the genre into a new, honest, raw medium is fascinating. What does this style look like without the sugar coating, lies, and glitter? You may find cinema that is far more pure than you had anticipated. Towards the end of the New Hollywood era would come one of its greatest offsprings: All That Jazz.

Fosse wasn’t just a staple of film. He was also just as distinguished on Broadway (in fact, he was a theatre mogul before he was a cinematic icon), and it was likely through his pursuit to push stage productions beyond their capabilities that he wound up on the big screen (where every little expression or detail was magnified for the world to see). His works almost felt metaphysical: we’re aware that they are plays, but we feel as though we are on the stage with these characters and amidst these set props. After Cabaret, Fosse worked on one of his biggest productions: Chicago (which would eventually be adapted into a Best Picture winner by Rob Marshall in 2002, and it presently is the last musical to win this honour). Marshall’s film was stylish and ambitious, but it was missing the visceral grit and truthfulness that Fosse always possessed (I can only dream of what his big screen rendition would have been like).

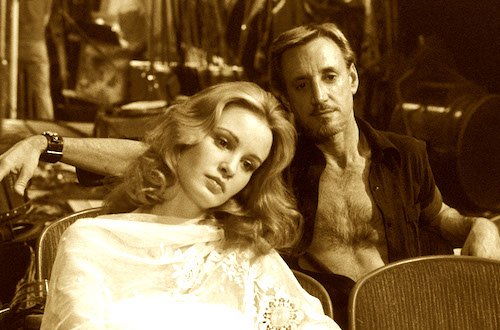

I bring up Chicago because he borrows the name of a song title from this production for All That Jazz, but there’s nothing jazzy about this film (unlike the Chicago number). Instead, here the title resembles the everything in between the show tunes, the big lights, and the curtain calls. All That Jazz is semi-autobiographical, with Fosse seemingly being as aware of his own mortality than ever. He had Roy Scheider — with his greatest performance — portray himself: here, he is one Joe Gideon, but his angsts, resentments, nerves, and sins are all the same. He is in poor health like Fosse himself, with a sick heart, major addictions, and high blood pressure, and yet he lies to himself every time he pops meds and drops eye solutions by staring at himself in the mirror to assure that it is “show time”. We’re used to the spectacles that Fosse pulled off, but not the biggest production he was achieving: his own life. It’s all an act. He isn’t happy despite his accolades. He can’t keep it together even though he seems to be in charge of two different industries. He’s not what we perceived him to be, and he wanted to lay out all of these revelations in All That Jazz: his magnum opus.

All That Jazz is a postmodern musical at times, where we are aware of what we are watching despite being engrossed by it.

Gideon is stressing out over his work and takes it out on his loved ones in various ways, including the very 8 1/2 act of frequent adultery (no matter how much of an artistic genius someone may be, their acts of selfishness are far more telling). Fosse is aware of how All That Jazz is going to make him look, but that’s kind of the point. This is his catharsis. This is his way of cleansing that of which he wishes to rid himself of. We are duped into watching his filmic admissions by thinking that we’re getting another signature musical of his (which, to be fair, we still do get), but this is as real as the movie musical can ever be. He’s not asking for forgiveness necessarily. He’s ridding himself of his personal demons, even quite symbolically. Gideon envisions an angelic figure in his dreams (played by a then newcomer Jessica Lange), and he fancies her, even when he is aware that she represents his eventual demise, not his joys. It’s by now that we slowly realize that All That Jazz savours its biggest choreographed number for Fosse’s dance with death, as he projects himself having a heart crushed by smoking, stress, and perfectionism (the major premise of the film is Gideon trying to keep fighting through his ailing heart). The film was released in 1979 (and was shown at Cannes in 1980). Bob Fosse would pass away in 1987 of a heart attack. He was sadly right on the money.

So many elements of All That Jazz scrutinize Fosse himself so much that there really is nothing left to dig for. We get his most vulnerable moments, ranging from his begging to stay alive within his fever dreams to his bouts of masturbatory exaltation in the shower. There’s nothing left untold. We are tricked by the opening sequence of All That Jazz featuring a jaw dropping dance number on the bare stage with countless performers. It’s shown as an audition and/or rehearsal so we aren’t swept away by something we aren’t getting (we’re instantly aware of the film’s confinement to the stage as a platform to practice on again and again, and not the end result). The film is full of roughness, so we’re not expecting to be fooled by the magic that won’t come. We see what Fosse/Gideon see. The rest of the film from there are additional attempts at capturing what Gideon is chasing after, and we share his incomplete vision. We finally get his masterpiece, but it likely isn’t what he had hoped for, but it’s what would ultimately define his life (in a number of ways), and then the curtain is finally drawn (via a zipper, and a stark reminder that, in reality, everything just ends. There is no encore.).

While other musicals try to sweep us away, All That Jazz makes us face the harshness of real life.

In this day and age, the movie musical is as nostalgic as ever, but many films are searching for the tenderness and escapist qualities of the genre. We may never get a film like All That Jazz again; if we do, it won’t be for a while. You can point at morbid musicals like Dancer in the Dark, but I’m talking less about the seriousness of All That Jazz and more about the dismantling of a genre in such a postmodern way. We’re always aware of what we are seeing when we watch All That Jazz, but we’re drawn in anyway. This is as temporal as a musical can be. It’s self aware, highly candid, and ugly: qualities musicals usually don’t possess. Fosse was trying to break out of preconceived notions in the best way he knew how: via this very same genre he was trying to break free from.

Like how Clint Eastwood had to detach himself from the western genre by killing it once and for all, so too did Fosse have to destroy that of which made him. Towards the end of New Hollywood, and well beyond the years of the American musical, All That Jazz gave us a final number to linger in our minds forever: the cynical adaptation “Bye Bye Life” (based on “Bye Bye Love”). It’s a song that is guaranteed to get stuck in your head, and is (considerably) a lazy change to boot, but there’s something so telling there. If Gideon’s final song is barely even his own and yet he rendered it his greatest achievement, what does that say about the palatability of music when it leaves the minds of the artists and is received by their audience? This was once an Everly Brothers cut. It became Fosse’s (and subsequently Gideon’s). It is now ours. What do we do with it? It doesn’t matter. Music will live forever, and it will transform from variation to variation. We won’t. We’ll decompose in the ground and will be fodder for other lifeforms, with the hopes of our legacies continuing on well beyond our physical selves.

In order for longevity, we have to acknowledge everything in between successes. The injuries from dancing. The sickness of workaholism. The crippling nature of addiction. Every mistake. Every gaffe. There’s something interesting about the instant response Stanley Kubrick had to the film upon its release in 1979: that it is the greatest film he had ever seen. These were huge words coming from a man known for exhausting his cast and crew with endless takes; a titan that was nearly macerated by his own perfectionism. Did he see himself in Gideon? Was he in need of soul searching like Fosse was? Or did Kubrick love the artistry of All That Jazz? The perfectly timed cuts. The textured cinematography. The rise of a visionary’s art whilst they themselves collapse. The featuring of the little things that most films neglect. Whatever it was, Kubrick was astounded by the one film that nearly was the movie musical to end all movie musicals. What else is there to see when Bob fosse presented it all? Enough time has passed that the genre has easily made a resurgence, with a new generation of theatre kids and cinephiles to gush over films of old and new. That’s fine. Unforgiven didn’t kill the Hollywood western: it just helped Eastwood move on from it. All That Jazz will forever remain one of the musical genre’s greatest achievements. No matter what it does to the style for you, you will feel something.

You’ll recognize that brave face that you put on everyday in Gideon.

You face the working day.

You face a big event.

You face change.

You face loss.

You face death, and, eventually, the end of your own life.

What it is, you’ll be facing it.

It’s showtime, folks.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.