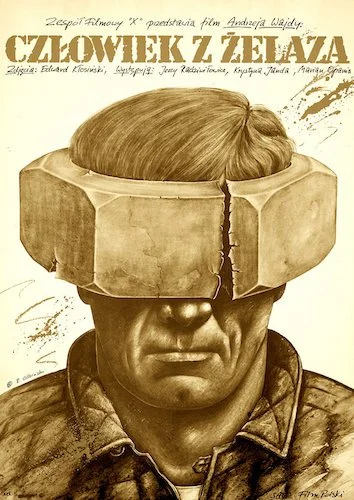

Man of Iron

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Man of Iron won the twenty sixth Palme d’Or at the 1981 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Jacques Deray.

Jury: Ellen Burstyn, Jean-Claude Carrière, Robert Chazal, Attilio d’Onofrio, Christian Defaye, Carlos Diegues, Antonio Gala, Andrey Petrov, Douglas Slocombe.

Man of Iron is an interesting Palme d'Or winner, as if it is more of a statement than an accolade given via subjective opinion. This is the first sequel to win the coveted Cannes prize, as it follows Andrzej Wajda's Man of Marble directly (both are political films that act as scathing remarks towards the political state of Poland, particularly the mistreatment of the working class). Man of Iron was released during the time of Solidarity in response to the many years of censorship that Polish filmmakers had to abide by. This film is a solid one, but it makes much more sense in context (either by viewing the first film, or by understanding its societal importance). It felt like the right place and the right time to reward it via Cannes’ jury’s powers vested in them. If not now, when could such a specific release have been honoured? Who can fortune tell?

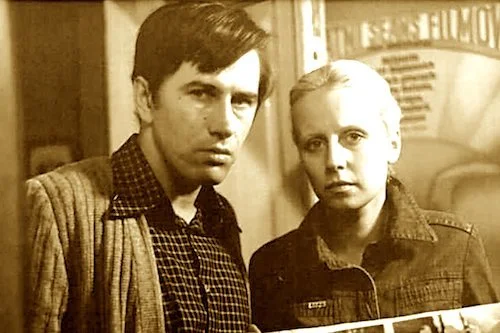

As a film, Man of Iron is quite fascinating, as we follow Maciej (the son of the main character in Man of Marble) and spot how he aligns himself as an important activist of his time. You can sense the genealogical importance of the moment if you see the previous film first, whereas watching Man of Iron on its own may not give you the same sense of destiny. Nonetheless, Maciej is still commanding enough that he begins to draw the attention of those around him, particularly the journalist Winkel. When paired with its sister film, Man of Iron becomes an analysis of political gestation and the passing down of sentiments. Alone, it is a conversation between a capturer, their subject, and the world around them. How do they act as catalysts during turmoil? Is it for better or for worse?

Man of Iron is a rare time where a film feels selected as a Palme d’Or winner for what it stands for, not on the film’s quality itself.

While a strong cinematic essay for Wajda to argue against the Polish government from decades prior until the instalment of the Solidarity union, Man of Iron is also a look at the relationships between the stories we tell and how they finally get ingested. It is about legacy on a minor level, thanks to its connection with Man of Marble, but it also acts as a nice contrast. This is about focusing on the state of Poland right now, particularly with the fear that the Solidarity movement could have been terminated; martial law was imposed from late 1981 to 1983 in Poland. In the name of the Gdańsk Shipyard Strike, the then-temporary lift on filmic censorship, and the support of workers across Poland, Man of Iron had to be celebrated when given the opportunity. While a thorough political film, this Palme d’Or win speaks more about the importance of the artistic voice amidst turmoil than about the film’s quality itself.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.