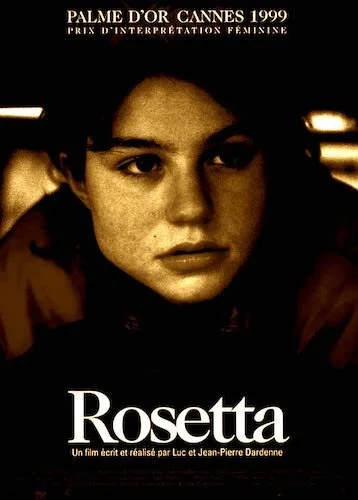

Rosetta

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Rosetta won the forty forth Palme d’Or at the 1999 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: David Cronenberg.

Jury: André Téchiné, Barbara Hendricks, Dominique Blanc, Doris Dörrie, George Miller, Holly Hunter, Jeff Goldblum, Maurizio Nichetti, Yasmina Rena.

If you ever want to know what the barest of filmmaking feels like, then watching almost anything by Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne will do the trick. The brothers barely even use music, let alone non-diegetic, to illustrate the sounds of their films. Credits just crash into the backend of narratives because there will never be a graceful or ushered-in ending to their films. With this in mind, let's look at Rosetta: a short-yet-tough film about the extents the working class has to go to in order to survive (a very common theme with Dardenne films). The film is marred by some recent notoriety, as David Cronenberg – the jury head of this year – and Pedro Almodóvar – whose magnum opus All About My Mother lost to a unanimous decision by the Cannes jury – continue to have to answer for this end result (as contemporaneously as Viggo Mortensen shoutout out Almodóvar during a Crimes of the Future presser).

Sure, All About My Mother is the better film, but what this infamy fails to highlight is how Rosetta is a very visceral and immediate experience. It's obvious as to how viewers would feel absolutely damaged by what they have seen on the screen by the time the petite Rosetta – at a brisk ninety three minutes – is over. We have invaded on someone's very private and vulnerable life here, as they are suffering to make ends meet (all due to powers against their control). Maybe the lucky Cannes jury can't identify with that level of struggle (not presently at the time of voting, at least) but there is an understanding that we all hurt, and there are millions of people going through financial hardship every single day. It doesn't take a rocket scientist to see the importance of knowing this, and the Dardennes can tell this point as simply and effectively as possible.

Rosetta is a harrowing-yet-minimalist film about the human experience for most of us: trying to find a way to make ends meet.

The eponymous Rosetta completes her probation period without her contract being extended, and she has seen this story before; she lashes out because there is no just cause for her termination, and now she has to worry about what will become of her (when she had the illusion of security before). She gets home to her abusive, alcoholic mother: they live in a caravan park in the middle of nowhere. She hates this life and is trying to get out of this well of agony, but her only feasible option has just concluded before she was ready to come up with a plan B. Her frustrations are completely relatable: we've all had to think on the fly of how we are going to make it past a determined amount of time with next to nothing. It's admirable how much the Dardennes are for the people and not about glitz and glamour; you can look on the flipside and acknowledge how crazy it is that films like these aren't actively prevented by industries (well, maybe Hollywood) because of how blunt they are about the elite and the unfairness of society.

Rosetta keeps going, both as a film and as a character, and each plot point is more depressing than the last. It is impossible to not be heart broken during this film. The Dardennes don't shy away from what we see either. We are forced to be exposed to the desperation of a young woman facing civilization's unforgiving wrath. By its end, Rosetta feels hopeless. Even after a bittersweet bow wraps everything up, I don't have much faith in the system that has failed poor Rosetta: it has failed all of us time and time again. Rosetta represents those that get left behind. Her story is going to continue, and lord knows where she will go, and unfortunately the Dardennes aren't going to be there to tell her story. They will have to move onto the next unfortunate soul again (in another Palme d'Or winner: L'Enfant), again (Lorna's Silence), and again (Two Days, One Night).

Part of the challenge with Rosetta is not knowing what is to come next after the open-ended finale, but we also have to take life one day at a time.

Rosetta comes close to being the best film these brothers have made. It's an early example of the kinds of confessions of the unheard that they're so good at telling. Not once does Rosetta as a character feel exploited, despite the hell that she is going through. Without feeling forceful, the Dardennes seem to be rooting for her as much as possible; you may feel like a guardian angel trying to watch over her during her darkest hour. This is all but a snapshot of the lower class and the ongoing crises that they live: one pay check at a time. There is no hope. There is only perseverance, and this can be hard to find when you are tried time and time again. Hopefully you don't identify with Rosetta and never will, but there is a chance that you do. So do I. Don't worry. We are heard. Loud and clear. By a serious film that won't gloss over all the details that make these events complete ordeals for millions (nay, billions) of us.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.