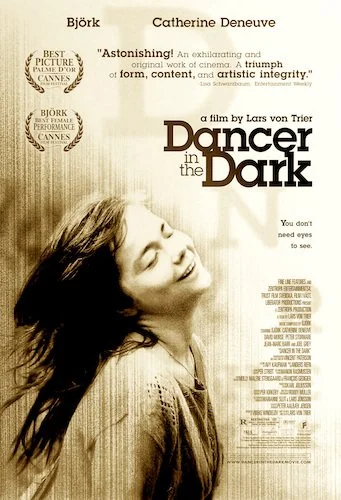

Dancer in the Dark

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Dancer in the Dark won the forty fifth Palme d’Or at the 2000 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Luc Besson.

Jury: Jonathan Demme, Nicole Garcia, Jeremy Irons, Mario Martone, Patrick Modiano, Arundhati Roy, Aitana Sánchez-Gijón, Kristin Scott Thomas, Barbara Sukowa.

The cinematic musical is usually reserved for great forms of escapism: particularly happy, blissful reexaminations of life. Then there are the darker musicals, and some may point to Sweeney Todd when you bring this up. Believe me. If you aren’t aware of this, you will be: no musical is heavier, darker, or more depressing than Dancer in the Dark. Lars von Trier’s stripped down musical stars the brilliant artist Björk as Selma: a factory worker whose eyesight is degenerating. Her condition is hereditary, and her son’s vision is bound to worsen to the point of blindness like hers. She’s legally blind by the time the film starts, and she has her coworker and best friend Kathy (Catherine Deneuve) recite to her what goes on in the films that they attend. Selma loves musicals, and always leaves on the second-to-last song, so the show will never end. During the day, she works as hard as she can to try and save up money for an operation that will prevent her son’s vision from deteriorating like hers is. She imagines the machine and city sounds to be the melodies of her own life’s musical, and of course Björk is the perfect star for this kind of a film; the soundtrack Selmasongs is quite excellent (then again, I’m speaking as someone who would proudly claim that Björk is one of their favourite musicians of all time).

As the film carries on, Selma’s vision worsens, and she gets into a lot of trouble when she runs into a number of obstacles (of which I won’t give away). Case in point: her life turns for the worse, and Dancer in the Dark becomes a completely different movie where Selma has to defend herself. My biggest gripe in a film that I otherwise love (actually adore) and find to be so inventive is how weak Selma’s character is represented during these times. It’s as if the film folds so she doesn’t defend herself (or even attempt to: the one trial scene where she has a chance to state her claim and doesn’t is forever a sour point for me, because there’s no reasonable explanation as to why she wouldn’t have said a single thing, even if no one believed her). In an otherwise powerful film, it’s some serious underwriting that always pulls me out of the moment. I get that Selma has a “golden heart” (as described by the anthological trilogy name of Von Trier’s that Dancer in the Dark is a part of), but that shouldn’t make her meek or naive. Bess is well intentioned but extremely easy to manipulate in Breaking the Waves (Von Trier’s greatest film), but the entire film devotes itself to this premise. Dancer in the Dark finds it convenient to make Selma a pushover where she easily doesn’t need to be.

Björk turns in one of the best performances of the twenty first century in Dancer in the Dark.

While that does affect how I feel about the film as a whole (a film where someone goes through hell and back feels exploitation-heavy when the characters can easily avoid the suffering they endure), I still am in awe of its best parts (which, to be fair, are a majority of the picture). Björk is absolutely perfect as Selma, with one of the most powerful performances of the new millennium. Her pain radiates off of the screen and into your soul. She is believable even at her most explosive and emotional. Between her performance and the incredible music (which compiles everyday sounds into homogenous music), this is a masterclass of Björk’s excellence as an artist. The film’s most dismal moments (its final act) are particularly shocking and will likely haunt you for the rest of your life, and that’s a testament to Von Trier’s no-nonsense approach to filmmaking: Dancer in the Dark is a pseudo Dogma 95 film that doesn’t abide by the movement’s rules entirely, but just enough to make as many moments as possible count.

Even considering its impossible-to-ignore missteps, Dancer in the Dark is harrowing, inventive, and overwhelming enough that the film itself is even harder to dismiss. I may have been a bit heavy on the film, but believe me when I say that it is a work I still highly recommend even with its imperfections: in fact, you may be able to look past my concerns with the film more than I do. At the end of the day, it’s still a worthwhile experiment with more successes than not, and it certainly is a film you won’t be able to ever shake off. Ever. Call my bluff if you don’t believe me. There really is no musical like it, and there maybe never will be, because Dancer in the Dark is excruciatingly tragic enough. Besides, it can’t be bested in this department, so trying won’t even be worthwhile: Dancer in the Dark is legitimately the heaviest musical of all time.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.