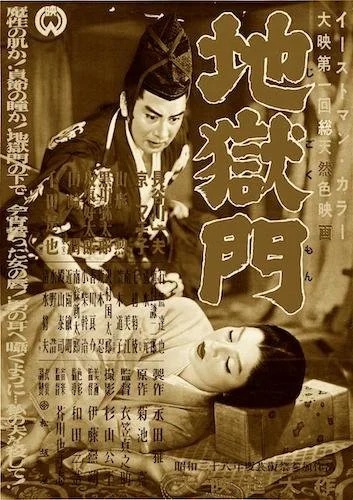

Gate of Hell

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. This is a Grand Prix winner: what the Palme d’Or was originally called before 1955. Gate of Hell won the Grand Prix award in 1954.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Jean Cocteau.

Jury: Jean Aurenche, André Bazin, Luis Buñuel, Henri Calef, Guy Desson, Philippe Erlanger, Michel Fourre-Cormeray, Jacques-Pierre Frogerais, Jacques Ibert, Georges Lamousse, André Lang, Noël-Noël, Georges Raguis.

The Palme d'Or would take over the Grand Prix award one year after Gate of Hell won, and that winner, Marty, was a stripped down, black and white, minimalist look at existential dread. There's something melodic about how much it contrasts the final original Grand Prix winner, as Teinosuke Kinugasa's romantic epic is in breathtaking Eastmancolor film, with elaborate sets and costumes. Both films are linked in one other way, outside of their short runtimes: their unique looks at the romantic drama. Gate of Hell places a Samurai in a position of falling in love with an already married woman during the Heiji Rebellion. Placing this story in such a tumultuous time helps add some chaotic chemistry between characters, whether they be lovers or rivals; this gestates into some real melodrama that tones out Gate of Hell a little more than your average period piece romance film.

Part of this achievement comes from those incredible colours that just pounce off of the screen: there aren’t many films from the 50s that look like Gates of Hell. This is easily a major draw that spellbound the Cannes jury at the time, but the bigger thought isn’t how nicely it looked back then: does it look great now? Actually, yes. Even with a not-so-good copy of Gate of Hell, you can see that there’s something special with the colour schemes, arrangements, and selections, as everything is strategically shot here (ranging from what costumes are used on which backdrops, for instance). I wouldn’t call the visuals a distraction when they certainly help elevate a film that relies on fervour to get by; it’s a narratively sound film, but what is felt at each moment takes precedent over what is causing us to feel.

Gate of Hell is a visually astonishing film, which helps heighten the buried passion within the story.

While rich in historical detailing and literary pivots, Gate of Hell does feel more like an aesthetic experience than one that compels me via its story. Even its stronger moments either feel expected, or anchored by what we’re witnessing and not how it affects us. Amidst some patiently told plot (which is a bit noticeable in such a short film, at an hour and a half in length) is captivating action and love, but these feel like extensions of the viscera of Gate of Hell. Nothing wrong with that, mind you. You may experience the film on its very surface, but even then this is quite a treat to behold. I wouldn’t call Gate of Hell unmemorable either, since its aesthetics are just this strong. Within the realm of Samurai pictures, however, you may not find that Gate of Hell is bolder or greater than many of the classics, but at least this one feels a teensy bit different (enough so that it’s a must-see for any fans of the genre that feel like they’ve seen it all).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.