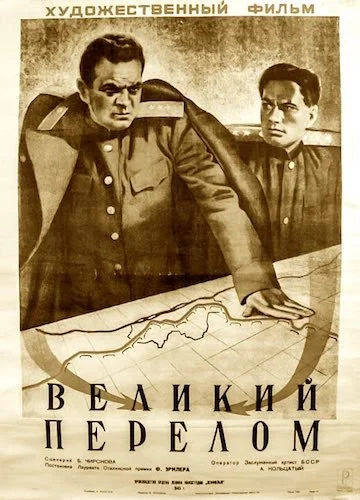

The Turning Point

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. This is a Grand Prix winner: what the Palme d’Or was originally called before 1955. The Turning Point won for the 1946 festival and was tied with ten other films.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Georges Huisman.

Jury: Iris Barry, Beaulieu, Antonin Brousil, J.H.J. De Jong, Don Tudor, Samuel Findlater, Sergei Gerasimov, Jan Korngold, Domingos Mascarenhas, Hugo Mauerhofer, Filippo Mennini, Moltke-Hansen, Fernand Rigot, Kjell Stromberg, Rodolfo Usigli, Youssef Wahby, Helge Wamberg.

If the very first full Cannes Film Festival could reward filmmakers that were already established in some way (like a legacy win), then perhaps The Turning Point could be such an instance. Fridrikh Ermier was already known for his contributions to Soviet cinema, particularly Vstrechny: one of the country’s first sound pictures (although his silent films may have been his forte). By the time he reached The Turning Point, he was known enough at least within the Soviet Union (and likely Europe) that this Grand Prix win could be chalked up to an identification of recognition. It isn’t a bad film, but I would easily go ahead and call it the weakest winner of the eleven-way tie (which is quite a long list). Of course, many of the nominees that didn’t win were from nations that already won an award (like Notorious and Gaslight losing because Brief Encounter won for Britain), but I can go through a ton of the unselected nominees that also feel stronger than The Turning Point.

Based in 1942 and 1943 during the Battle of Stalingrad (where the Soviet Union held off Nazi Germany’s attempts at overtaking the city of the same name), The Turning Point solidifies the triumphs of the team of colonels and generals that protected what would now be known as Southern Russia. Ermier is a propaganda filmmaker at heart, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing when it comes to the art of a film (although the ethics are most certainly questionable), so The Turning Point is definitely proud of the Soviet Union’s accomplishments, and the film is shot in such a glorifying way. That’s honestly where the film is at its strongest: how these defensive strategies and its major players are filmed.

The Turning Point is well intentioned and well shot, but rather disengaging as a film.

The problems lie with how the actual story is told: in a rather undemanding fashion. It actually feels strange that a war film this artistic and based on real events feels this distant. Maybe it’s the lethargic pacing or the reliance on the Soviet Union’s victory alone to drive the picture that make The Turning Point feel so held back. The film is satisfactory, but I don’t feel as wowed as I think Ermier wants me to feel with The Turning Point. it’s not a bad film necessarily, but it takes a lot for a film this aesthetically and passionately driven to feel cold. Maybe it’s single-noted with what it is trying to convey, but it at least has good intentions (outside of the possibly propagandistic, of course), enough artistic successes, and noble performances to be watchable. It just doesn’t scream “Grand Prix” or “Palme d’Or” winner to me.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.