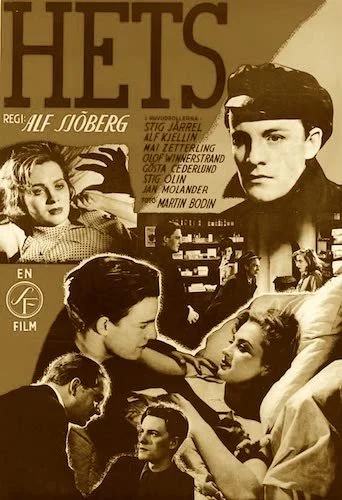

Torment

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. This is a Grand Prix winner: what the Palme d’Or was originally called before 1955. Torment won for the 1946 festival and was tied with ten other films.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Georges Huisman.

Jury: Iris Barry, Beaulieu, Antonin Brousil, J.H.J. De Jong, Don Tudor, Samuel Findlater, Sergei Gerasimov, Jan Korngold, Domingos Mascarenhas, Hugo Mauerhofer, Filippo Mennini, Moltke-Hansen, Fernand Rigot, Kjell Stromberg, Rodolfo Usigli, Youssef Wahby, Helge Wamberg.

Ingmar Bergman’s earliest work as a director is fine. Not great. Not awful. Fine. They’re watchable with hints of creativity and signs of what would come, but he would need to get to a different place as a visionary. At this point in his career, he was a better storyteller than a director, although he would definitely toss in some visual ideas that showed that he was at least trying to improve in these additional ways. He was always obsessed with how the human mind works as a problem solver and a moral compass, but he wasn’t quite sure how to show it like he eventually would be able to. At this point, the best indication of what Bergman was capable of actually came from another mind: Alf Sjöberg, whose film Torment is as much his own achievement as it is an artifact in Bergman’s filmography. This is a considerably dark film for its time: abuse within the education system (a teacher that mistreats a young student? This clearly is a Bergman film), without much romanticizing of the subject matter either. If anything, Torment is willing to get outright morbid.

Like many films about “school” at the time, Torment is an allegory for something much bigger. With Bergman, it could mean many things: society willing to neglect its individuals, parents that use heavy handed ways of disciplining their children, or God being a loving but punishing being with his followers. Sjöberg isn’t oblivious to these possibilities, as he lets Torment feel like a palatable metaphor. He does bring out the screenplay’s psychological and belief-based cynicisms with interesting camera techniques, a generous use of shadows, and unflattering angles: we feel like we are invading the personal spaces, privacies, and minds of those involved. These include the most abused student Jan-Erik, and his love interest Bertha, particularly under the hateful gaze of the monstrous teacher (appropriately nicknamed “Caligula”).

Torment is willing to get outright shocking when it needs to in order to fulfil its point on corrupted authority.

I do feel like Bergman would be able to fully realize what he’s trying to say in later films, but Torment is as good as you’re going to get with his early work. Sjöberg feels like an artist willing to guide Bergman in the right direction, and the two together get pretty far with Torment (especially in the third act when the film dares to overstep its boundaries, which I am very grateful for, given its purpose as scathing commentary and its necessity to get its unglamorous points across). It still feels very basic, especially from what we’ve seen come after: very straight forward character symbols used in direct ways. Sjöberg and Bergman go the distance with what they have, and that makes Torment at least quite good enough. It may not ring as a classic would with most viewers, but I’ll be damned if many people find this film worse than interesting. Torment is good. Really good. It’s the psychological drama you maybe didn’t know you needed to check out.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.