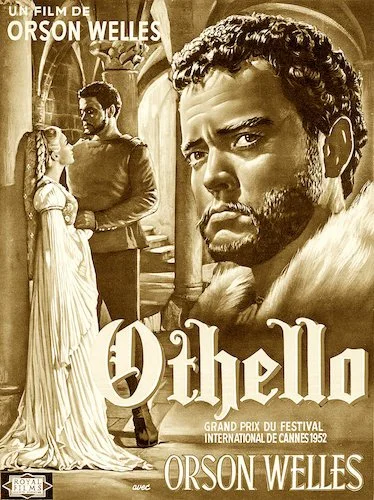

Othello

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. This is a Grand Prix winner: what the Palme d’Or was originally called before 1955. Othello won the Grand Prix award in 1952, which it shared with Two Cents Worth of Hope.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Maurice Genevoix.

Jury: André Lang, Chapelain-Midy, Charles Vildrac, Evrard De Rouvre, Gabrielle Dorziat, Georges Raguis, Guy Desson, Jacques-Pierre Frogerais, Jean Dréville, Jean Mineur, Louis Chauvet, Madame Georges Bidault, Pierre Billon, Raymond Queneau, Tony Aubin.

Orson Welles used every opportunity to prove he wasn't a one-hit director after Citizen Kane. While I do think that is his best film, my favourite discoveries came after seeing what he would accomplish next. He was forever trying to use new ideas as both a filmmaker and an actor in a medium that was starting to learn its own traditional self by the time he started. This comes heavily into play by the time he reached Othello, as the works of William Shakespeare are often treated as faithfully as possible; even it you look at the changes in something like Laurence Olivier's Hamlet from a few years prior, there's still a call for theatrical standards. That's also the case for Welles' turn at being the star, director, and producer of his own adaptation. We wouldn't get too many of the major deviations like Akira Kurosawa's Ran or Robert Wise's West Side Story, or highly abstract versions like Joel Coen's The Tragedy of Macbeth (or even the romanticized teen versions: O, 10 Things I Hate About You, Romeo + Juliet, et cetera).

Welles' Othello was as traditional as he saw fit, not because he wasn't daring. He was a theatre mogul before he dominated the big screen, after all. It probably felt proper to honour a Shakespearean story as he would on the stage, only now he had a decade behind the camera in his bag of tricks. So, yes. Othello is traditionally told as a story, with Welles playing the eponymous king, and the whole nine yards is here: a kingdom that can't see past race, Iago's manipulations of a temperamental leader in order to assume his throne, and a tragic downfall of someone who got bested. Of course, it is worth noting that the biggest sour note here is that Welles performed in blackface, as was sadly the norm for productions of Othello, so while it can be overlooked in a historical context, it doesn't make the act right or seeing Welles partake in such a disgusting act any easier. It's something you have to accept as soon as you commit to watching, or it may spoil your anticipation from even watching at all. It's a great film, but I cannot fault anyone from being turned off by something as disgusting as minstrel culture, even if Welles wasn't trying to be offensive.

Othello balances a traditional take on the source material with some advanced artistic techniques.

The story is what you'd expect from a rendition of Othello, outside of some scenes moved around within the film's timeline and some culling to shorten the feature. How this story is presented, however, is the big ticket here. Welles goes crazy with his signature canted camera angles, heavy use of shadows, godly framing of light, and so many other techniques that bring this story (one that's been experienced many times before) to new life. If anything, outside of the backwards use of blackface, this feels like the superior version of the story that I've ever seen, and the majority of this magic comes from how incredible this film looks and feels. Even the editing feels dynamic, so any non-Shakespeare fans will still feel glued to the screen with how much this film booms.

Welles' experiment here is the most true to himself he was up until this point (Chimes at Midnight would continue this train of thought), as he married the two biggest passions he ever held: the stage and the silver screen. At times, Othello does feel like a theatrical production done through a camera lens, but it doesn't only feel like that. Welles makes sure to remind you that this is a film after all, and he achieves this feel with all of his noticeably filmic creative choices. This really is the best of both his fortes combined into one, and you can't go wrong with fulfilling such a risk when you're as confident as Welles is. You can't just shyly adapt Shakespeare. You have to almost be full of it, but also correct in your certainty of your own capabilities. You may come off as pretentious if you're wrong. You'll feel like Orson Welles if you're right. Many directors try to feel like Olivier and Welles when they direct Shakespearean works. They're not all right.

Orson Welles directs Othello with the utmost of confidence, and breaks through conventional filmmaking with this unprecedented version of the play.

If Olivier was a then-modern approach to the handling of a Shakespearean film the old fashioned way, then Welles' Othello feels like a faithful approach to artistically progressive filmmaking. He is only partially rooted in what Shakespeare wrote with Othello, but he uses this opportunity to keep breaking other rules his own way. It's a film that will please both sides of the argument: those that think Shakespeare's works shouldn't be changed, and those that love to see an authorial touch on any adaptation. All of this passion and creative control makes for a highly connective rise-and-fall of the eponymous character, and a devastating experience that anyone – literature or film major, or neither – will feel in their very bones.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.