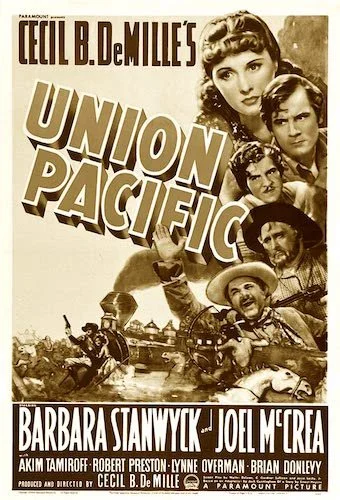

Union Pacific

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. This is a Grand Prix winner: what the Palme d’Or was originally called before 1955. Union Pacific won for the 1939 festival in 2002, as the first Cannes Film Festival was cancelled due to the start of World War II (a jury selected a winner from the original submissions).

Look. I'm going to level with you right off the bat. I'm not the biggest fan of Cecil B. DeMille. While his technical achievements have always been impressive (even the now-dated ones like his overuses of rear projection), his storytelling in a number of his films has been lacklustre. You can't just make long films that aren't interesting just because you shove many high budget techniques in them (ahem). Case in point: Union Pacific is one of his better films, and even then, I would consider it pretty good and nothing brilliant. This is what the 2002 special jury at Cannes thought was the best film of the original 1939 selection (as if The Wizard of Oz wasn't a part of the list), but maybe it felt the most like what would have won the Grand Prix (now known as the Palme d'Or) back in the day.

Based on the construction of the eponymous track, this western contains the colliding of differing motives for having the railroad built, ranging from financial gain to travel convenience. This is an appropriate allegory for DeMille, who sought to take the western genre to new places with Union Pacific, and opted to make the genre bigger and more technically astounding than ever before. He also was directing three works at once, and while his dreams are here as a producer and filmmaker, his full attention is clearly absent as an invested storyteller. Characters brush by each other and they don't really form a substantial connection, outside of the characters of Jeff Butler and Molly Monahan (played by Joel McCrea and Barbara Stanwyck, respectively), which I would chalk up to the acting more than anything else.

Like most Cecil B. DeMille films, Union Pacific prioritizes its scope over its story.

Still, the amount of work put into the scope of the film is what matters the most (which is almost always the case with DeMille), and it feels like an impressive shoot even eighty-odd years later. Ignore the occasional moments where the effects have aged poorly (like when you can tell you're obviously looking at miniature models of scenes), and you have a tale whose impact is felt by the heavy machinery and blood, sweat, and tears of the workers and characters on screen than anything else. Outside of these kinds of elements, Union Pacific isn't quite as memorable as it could have been, should the story have been fine tuned and prioritized just a little bit more. However, I do feel like DeMille was a relic of the past: a silent film director that operated similarly during the era of talkies. He worked on multiple projects at once, tried to push the technical capabilities of the medium, and keep the barest of basics of storytelling. It maybe didn't work as well as one would think, in my opinion, but I do find something at least a little interesting in this regard as someone fascinated with film history: as if a director of a bygone era that was slated to be the future was actually stuck in the past.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.