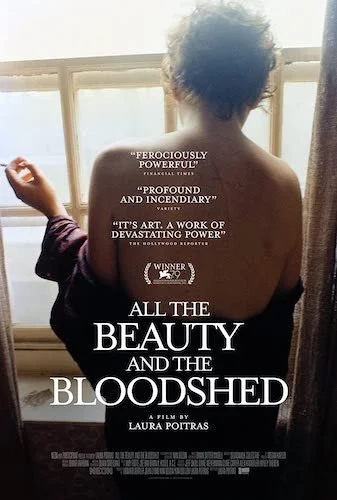

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

We’re covering the Academy Award nominees that we haven’t reviewed yet.

One of my all time favourite albums is The Velvet Underground & Nico, and it is one I know inside and out. It depicts a New York City that is liberated, free, and uninhibited by society’s limitations. It also acts as a cry for help that is pushed from the gut, particularly when you hear a song like “Heroin” that highlights the rush an addict has while recognizing the dangers that have yet to come (particularly the apocalyptic image of dead bodies being piled up in mounds). While a cacophony, the album is simultaneously gorgeous. It simultaneously showcases the two sides of civilization that were being hidden by the populace back then: the kinds of sexual and personal explorations and joys that were being hidden and shamed, and the actual dangers that were also being ignored in favour of a lie: the world is fine, as long as it is portrayed in this way and we dismiss all of the problems that are truly there.

Laura Poitras’ latest documentary, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, contains two cuts off of this album: the numinous “All Tomorrow’s Parties” and the album opener “Sunday Morning”. The film also dives into the underground scene of NYC, and we are steered by the film’s subject: photographer and activist Nan Goldin. Now in her late 60s, Goldin has a fountain of stories about the film’s namesake: two hidden worlds that beg to be learned about. There are the lifestyles that have been chastised and threatened (the LGBTQ+ communities of the 60s, 70s, and 80s, positive sex work, and the like), many of which have been covered before by Goldin and her acclaimed slideshow pieces (including The Ballad of Sexual Dependency). When the media could hide the voices of millions, Goldin would be the platform that captured them all, and her venue would be gallery exhibitions and photo books. Well, these are stories that Goldin has shared already, and she will go into more detail than ever before in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, but her priority in this film is quite different: she will stop at nothing until Purdue Pharma and the Sackler Family are taken down.

Nan Goldin’s legacy and heroism is captured at its fullest in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed.

Huh? That sounds like quite a different modus operandi than all of the other goings-on in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, and the film feels like it embodies two natures at first. Split into seven chapters, the film begins each section with Goldin’s photographs from one of her collections with the artist narrating over what we can see (we do hear other voices as well, creating a fuller story). After the candid revelations are done, we cut to the Goldin of today: a leader of the advocacy group P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now). Their goal is to get the Sackler family name (the family that owns Purdue Pharma) erased from all of the art galleries and institutions that have welcomed their donations and plastered the surname on their walls. We quickly learn (if we didn’t know already) that Purdue Pharma is responsible for the deaths of countless lives in a plethora of ways, including hospital patients getting prescribed opioids and then dying from addiction and overdoses.

The film’s two sides converge somewhere in the middle, when it becomes clear how the communities Goldin associated with got hit by the shady practices of pharmaceutical companies. Goldin herself — a survivor of domestic abuse — was treated for her injuries and subsequently became addicted to drugs because of what she was prescribed. We eventually dip into the AIDS crisis and how many lives were lost because of neglect: further proof of the two trains of thought coinciding much more than one may initially think. Once this connection happens, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed keeps going in other unpredictable ways, with a quick reminder of how awful psychiatric care was back in the 60s (Goldin’s personal recollections will break your heart, and I suggest trying to skim through the medical records that flash on screen as much as possible, because the fuller picture of how awful treatment was back then is crucial to the overall thesis of this film).

Yes. The two halves don’t seem to align, but they wind up being inseparable. In the grand scheme of things, lives are never taken seriously when business is made to be a priority. Money places names on walls, erases bad press, and keeps vicious cycles going. Without spoiling too much, P.A.I.N. actually seems to succeed in their mission roughly halfway through All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, but that obviously isn’t the end of the story: we are reminded, once again, that money will always help the wealthy succeed even when they are seemingly losing. Nonetheless, the protests staged by P.A.I.N. are beautifully executed, with death warrants disguised as prescription slips raining from the skies of the Metropolitan Museum of the Arts, P.A.I.N. members posing as corpses amongst a red carpet of blood, and pill bottles floating in institution fountain beds. P.A.I.N. is speaking to those in the art world: ones that will observe and dissect what they see. They get their message across with performance-art-based excellence. Even in its most triumphant moments, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed feels morbid, but its subject matter was never going to be light.

An example of a protest set up by P.A.I.N. in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed.

The entirety of Poitras’ masterpiece is haunting from the very second it begins. A large number of Goldin’s photographs have oxidized with a gold rust seeping through what we can see: as if the blood is spilling from this history, and is becoming impossible to ignore as time passes. Seeing the still images march through the feature is quite chilling: as if these static photographs are their own corpses that still possess much life in them in the form of those thousand words that these images are worth. Much of the documentary is vulnerable while being eye opening, and the influx of graphic information and nauseating realization makes All the Beauty and the Bloodshed so difficult to stomach. It also is impossible to shrug off: I wasn’t drifting off for a single second of this film. It takes so many different instances of abuse and devastation — with pinches of joy from the underground — and blends them together to make a startling testimony that resonates in a messianic way.

I’ve been a fan of Laura Poitras since Citizenfour, particularly because she has a knack of knowing where to be at exactly the right time, and is able to capture what the world needs to hear. She achieves so much more with All the Beauty and the Bloodshed: an undeniable tapestry of resilience and ruin. No matter how punishing the film feels, there is that ray of light that keeps it going (and us looking ahead and hopeful for more change): Nan Goldin. The film is as much hers as it is Poitras, and the documentarian allows the photography/activist to make the best use of the cinematic space around her (as if she is curating an empty space for her next show). While the end result is tremendous, I can only imagine the two visionaries tackling so many other worldwide crises that are similar to the ones in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. It could have gone on for an extra five hours, and I’m certain that it would be just as relentless as that first minute. It’s no wonder why the Venice International Film Festival saw fit to award All the Beauty and the Bloodshed the Golden Lion (only the second time in its history that a documentary has won this top prize). It is easily one of the best films of 2022, and it already feels like a magnum opus of documentary filmmaking that will set a precedent in tone, ambition, and prestige for decades to come.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.