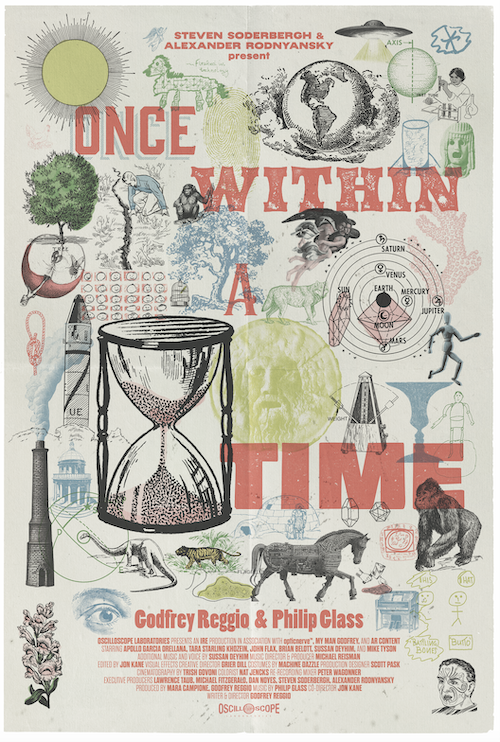

Once Within a Time

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

It’s no secret that the majority of civilization is concerned about where we are headed as a species. This also wouldn’t be the first — or the last — time that artists use their medium to convey both their uncertainties and their hopes. I don’t mean to begin a review so vaguely, but once you watch the experimental featurette Once Within a Time, you’ll understand the importance of scaling up these sentiments. Directed by Godfrey Reggio (Koyaanisqatsi) and Jon Kane (who has acted as editor for previous Reggio films Visitors and Naqoyqatsi), Once Within a Time is a Georges Méliès film for a new age where the start and end of the cinematic medium converge into a vortex void of linear time; the technologies of past and present suffuse a dialogue-free, forty-minute playground (the film is over fifty minutes with credits). Gone are the days when Reggio shoots time lapses of societies and civilizations and allows these pictures to tell their own stories. Here, he and Kane have an alarming message that is painstakingly pieced together as both a love letter to the history of film and a cautionary tale of where we are heading as a species with the unfaithful turns of technology. With the return of Reggio associate Philip Glass — whose score feels reminiscent enough of his Einstein on the Beach material here to evoke feelings of time as an abstract sensation — Once Within a Time is an exposition of history, art, and science bottled in this filmic vessel, ready to be shared and ingested.

There is a story buried deeply within this featurette, and the best way I can describe it is that Once Within a Time dreads the current state of the world and its dependencies on the brainwashing tactics of social media and other technologies (don’t worry: AI gets its own images of scorn here, too). As we see a cryptic being I can only imagine is Mother Nature singing an operatic song (of sorts: it’s tough to tell when her vocals get replaced with other sounds in post), it’s clear that Reggio doesn’t feel comfortable shooting the world as it is like he once did. My takeaway is that the world has changed drastically over these decades and now it is in a state of peril, pleading for us to make changes. Why aren’t we listening? Because we are tied to our devices, of course. The protagonists, so to speak, range from a man and woman whose heads are enclosed in cubic cages (I suppose this renders them impenetrable to change), as well as a cast of children who continuously face tall orders throughout Once Within a Time, including being fed constant information, having their visages scanned and plotted via facial recognition software, and more.

While Once Within a Time does possess a slightly biased look that technology as a whole is problematic (which can come off as a little austere), it does have a point in the context of how this argument is displayed. Because Once Within a Time is shot and edited to represent a silent film from the nineteenth century (choppy frame rates, signs of aging and all), it’s easy to connect point A to point B: the film worries not just about the state of the world but the heartbeats of the art that keeps us going as human beings. Once Within a Time clearly views numerous modern forms of entertainment as void of art, as we see some pretty straight forward symbols throughout the first half of the film; one such example is a beaker overflowing with dollar signs that also carry the same consistency of notifications pouring during a live feed. In case that wasn’t obvious enough, gigantic emojis in a silent film lens bring things full circle: from one voiceless, visual conveyance of story and message to the modern day form of it.

Image courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories.

We continue with these images that feel quite blatant, and this was before the apes made an appearance. Yes. We harken back to 2001: A Space Odyssey’s ability to combine past and future — as well as the depiction of technology as a harmful utility — through the use of chimpanzees and more; you even see a device — likely a mobile phone — held upright like the monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s science fiction masterpiece. There’s a grid of monkeys with their eyes glued to their devices as we faintly hear a commercial blasting out of their speakers: they have fallen victim to the system. In case Once Within a Time wasn’t upfront enough, perhaps the image of a chimp ripping off a VR headset to snap back to reality will drive the message home.

Mother Nature returns and sings her song, as the children shown throughout sit at her feet and listen to her cries. Meanwhile, the man and woman with caged heads are given thunderous applause by an audience of marionettes: clearly puppets that are instructed on how to act. With these two opposing images in mind, I do wonder about an earlier sequence involving — and you have absolutely read what you are about to read, so don’t worry about double checking — Greta Thunberg’s face glued onto a marionette and trying to get the attention of others. If the film’s message is for children to change the course of society and to instil positive reinforcement in a world full of surrendered cynicism, what exactly is it saying about Thunberg? Is Once Within a Time accusing her of being a political plant that is guilty of being manipulated? Is she meant to be an example of hopeful change? For a film that’s as direct as Once Within a Time typically is, it can be a bit of an enigma as well.

If that “appearance” wasn’t startling enough, be prepared for — and, again, this is real — an actual cameo from none other than Mike Tyson that somehow makes his pop-in in The Hangover seem normal. Unlike Thunberg’s, I can actually make more sense of this symbol (believe it or not). As Tyson talks to this group of kids towards the end of the film — in a boxing ring with severed ear sculptures at each corner, no less — I instantly understood that this is a man who is identifiable with the notion of the changing of one’s heart. If Mike Tyson can lead a life of anger and sin and become a peaceful individual who inspires faith and hope, maybe he’s the best man for the job here in Once Within a Time (and the added allegory of “deaf ears” doesn’t hurt, either).

While Once Within a Time can be alarmist in nature (the sky literally crumbles and falls at one moment, perhaps as an allegory of the hopelessness of society or to mimic the fear-mongering hyperboles of clickbait, fake news culture), it is also light, fluffy, and magical in its clever aesthetics and dreamy creativity. As people dressed up in 1890s attire walk amongst binary codes, you get the sense that Once Within a Time is aware of the fears of the past that were consoled or resolved (depending on whether or not society had legitimate reasons to be worried about certain matters, technological or not). The end of the picture leaves us with the question “Which age is this? The sunset or the dawn?”, noting the cyclical nature of history and civilization. Mind you, there is still a clear distinction here that Once Within a Time, Reggio, and Kane, do fret the impending sense of doom, hence the call-to-action for the youths of today to right the wrongs of the generations that came before them; the children shown throughout the film run with more freedom than anyone is ever depicted elsewhere. The film understands the power of images to direct messages: if Emojis can tell an entire story or sentiment, then so can the ways of silent cinema. While Once Within a Time comes close to being overwhelming with its messaging, Reggio, Kane, and company have enough restraint and whimsy to render Once Within a Time as much of a celebration of art, humanity, and progress as it is a loving warning.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.