Killers of the Flower Moon

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Can you find the wolves in this picture?

Martin Scorsese and the Killers of the Flower Moon trailer encouraged us to keep our eyes open weeks ago. Now that the American legend’s first western has dropped, we get tossed that line fairly early on while Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) is reading a book on Osage history and spots this caption underneath an image: “Can you find the wolves in this picture?” Killers of the Flower Moon is a slow burning descent into the desecration of paradise, and we are caught trying to spot intruders in as many static frames as possible: the concern isn’t whether or not we can find these proverbial wolves (their disguises don’t fool us), rather it’s how well do these wolves blend into their surroundings. Scorsese’s latest film is equal parts his artistic side (with how it is shot, some of the creative additions, and the gradual, stealthy pacing) and his dangerous one (snappy editing courtesy of mainstay Thelma Schoonmaker, graphic violence where necessary). It is a celebration only because of the amalgamated trademarks that have cemented Scorsese as one of the greatest directors of all time, but Killers of the Flower Moon is otherwise a cry out of tragedy through and through.

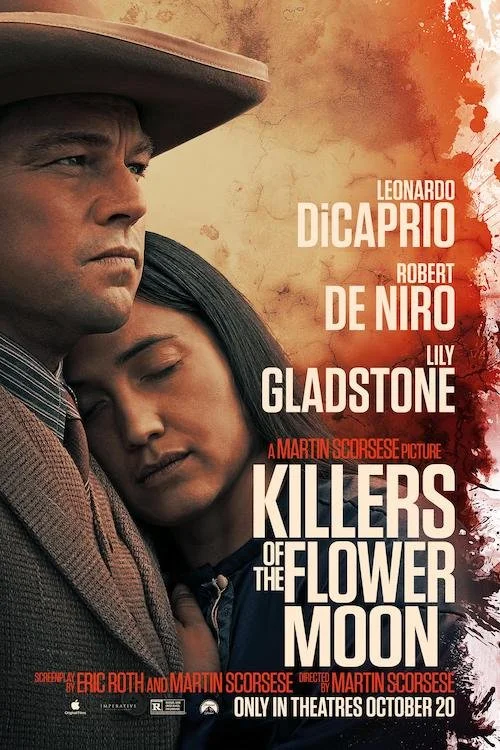

We follow Ernest to Oklahoma years after the Osage Nation has discovered oil underground and have become a wealthy civilization. Ernest meets up with his uncle, political game-changer William King Hale (Robert De Niro). It isn’t long before William gets down to brass tacks and asks nephew Ernest if he likes indigenous women. At first, it seems like a hint of racism behind a curious uncle, but we quickly realize that this is the first of the countless schemes that William has up his sleeves (that we see in the film, anyway). As Ernest begins driving people around for work, he is hired to pick up Mollie (Lily Gladstone) who he quickly takes a likening to. Now the overlaying question we are tasked with is whether or not Ernest actually loves Mollie, or if he has been manipulated by his uncle into wanting to inherit her Osage wealth.

Killers of the Flower Moon is a masterful film by Martin Scorsese which ranks up there amongst his best works, and that says a lot.

Based on David Grann’s non-fiction novel Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, major beneficial changes were made to change this film from the solving of murders by BOI agent Tom White to the poetic, acidic tale of deception and psychological torture zeroed in on the marriage of Ernest and Mollie Burkhart. The film is devoted to the notion of storytelling and how news and voices are conveyed via artistic or journalistic media. We see silent newsreels and films throughout Killers of the Flower Moon, and parts of the film are even shot to feel like modernized homages to the era (with a couple of title cards to boot). We also get sparse, overlayed narration from Ernest and Mollie, but this is infrequent enough to stick out as devices. The film kicks off with a slow motion, almost Hollywoodized sequence commemorating the Osage Nation discovering oil (and it is a beautifully on-the-nose moment by Scorsese who is almost never corny: a means of stating this is exactly where the story should have ended, and not the three-and-a-half hours of corrosion that follow). With the concept of sharing voices and testimonies over the course of history, I refuse to spoil the shocking, unorthodox way that this film ends, but all I will claim is that it is a dichotomy between Westernized entertainment and traditional artistry both being used to deliver the same message (there’s even a very meta moment that felt like one of the boldest moves ever made by an auteur who has made countless before).

Even though Killers of the Flower Moon dips into its ugly side quite early on, it’s astonishing how much deeper, and deeper, and deeper into sin and corruption we go. Thanks to the fluid, finessed editing, these three and a half hours zip by before you’re ready for the film to conclude. In ways, this film feels — in a very small way — like Scorsese’s There Will Be Blood, with the gorgeous American landscapes drowned out by the blood of oil (Paul Thomas Anderson’s film is an olive green, whereas Killers of the Flower Moon is a muddy amber) and the score acting as pulsing guilt (the late Robbie Robertson’s score here is minimalist yet vital as the brooding dread throughout the film, similar to what Jonny Greenwood pulled off with his magnum opus). It’s obvious to say that DiCaprio is great as Ernest in this film, and it may be a pleasant surprise to hear that De Niro is at his best in years as William King Hale. The biggest takeaway is how Gladstone steals the entire show with the most natural, small-scaled acting of the whole film; while I want the other two leads to be nominated for Oscars, the Academy Award for Best Actress — at this point — must be Lily Gladstone’s. Gladstone speaks through her glances, especially when her character struggles with diabetes (I’ll leave this subplot alone and will let Gladstone drop your jaw with her masterful acting).

As strong as the other two leads are, Lily Gladstone makes Killers of the Flower Moon her own with one of the best performances of 2023.

While Killers of the Flower Moon establishes itself as a true crime, downward spiral from early on, it becomes fascinating once it tosses in its actual main reason to exist: the twisted concept of nurture. How do we take care of those we love? This is the dilemma Ernest finds himself entangled in as he tries to be a doted husband and father to his family whilst being the best nephew for his monstrous uncle. By the end of the film, we’re never entirely sure where Ernest falls on the moral compass, and it’s better that way. It doesn’t matter. Once you put loved ones — or anyone — at risk, your intentions don’t mean anything. This reason alone is why Killers of the Flower Moon excels tremendously. While a depiction of the Osage Indian murders would have been important enough (and we do get this crucial history in spades here), we get a dialled-down story that shows the tragedy on a personal level. We understand how bad these murders got across the board with the various intercuts of said information, but getting to know Ernest and Mollie Burkhart is what will rip your heart apart.

Killers of the Flower Moon is excruciating to withstand not at any fault of the film. Instead, its agony comes from the neutrality that these awful actions are showcased, leaving you to stare at them square in their faces (of the guilty living, and the dead that cannot speak for themselves). Scorsese is one for style, but he aims to be respectful and truthful here; he’s got enough artistic merit in his pinky toe for it to spill into every sequence without him having to try. The end result is a film that is typically Marty but also quite unique even for him: a parade of turmoil and culpability. As we assimilate amongst the sheep and the wolves, we know the dangers of these situations and the swiftness of how fatal these greedy toxins can be. We see a thriving society for mere moments; it is quickly preyed upon and left to fester with open wounds. As we are tasked with finding the wolves in this motion picture, you will feel changed once you leave the theatre. Then comes the final objective: finding the wolves amongst you in a world that continues to thrive on the exploits of others. For anyone who wants to peg Martin Scorsese as clueless for all of his Marvel talk, Killers of the Flower Moon is evidence that his head is as switched on as it ever was. It’s a masterwork in a filmography full of many, and it’s the best Scorsese feature in years.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.