Anselm

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

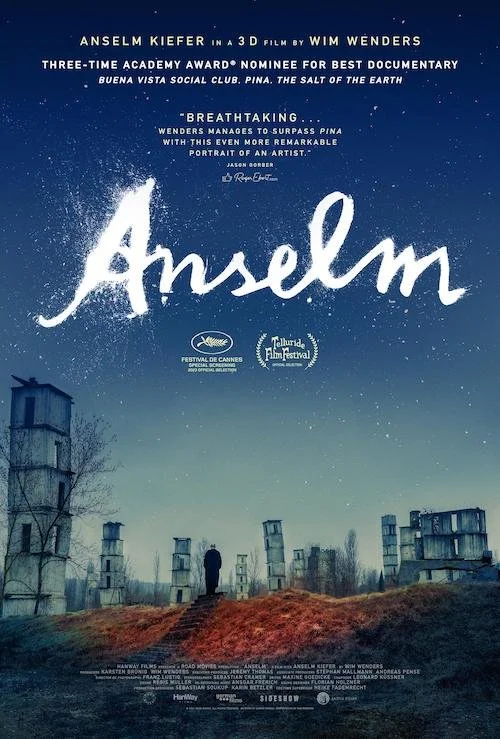

What made Wim Wenders’ Pina such an instant success is how quickly the music documentary whisks you away in its premise: to place you in the choreographed realms of Pina Bausch’s imagination. With some of the best use of 3D I’ve ever seen in a theatre (3D glasses act as a portal to join in on the dances here as Bausch’s cast coasts around you), Pina planted you squarely onto the stage of life to honour a legend of her craft. Wenders’ latest documentary, Anselm, vows to do the same, this time with a much more stoic art form than freestyle dance. We witness the paintings and sculptures of artist Anselm Kiefer this time around, and his pieces almost always evoke a strongly political message, be it comments on war, the desolation of Germany through various points of history, and the massacres of the Holocaust. There are also religious sentiments taken from the Kabbalah that get applied to his art: lights at the end of very long and very dark tunnels. While Pina is vibrant and colourful, Anselm is clay-grey and chilling instead. We aren’t carried away by the dancers of eternity: we are instead placed in the gardens of purgatory, as we walk around eerie sculptures and paintings and are forced to grapple with what they are depicting (be it abstract paintings, or an abandoned airplane that looks like it has obscure projectiles popping out of it).

While it doesn’t sound appealing to watch an artist work and see static artworks just exist, let me assure you that this is some chilling documentative filmmaking that evokes the feeling of being in a gallery or museum and getting moved to tears or horror by the power of said art. Wenders places these pieces in appropriate settings as well, as if the world is Kiefer’s institution to claim as his own. Furthermore, this creative choice makes for an even heavier realization when you notice that the world does feel like a fitting place to house Kiefer’s creations because of how cold and empty it has gotten: this is a statement on how hostile the world has become and a testament to the unfortunate timelessness of Kiefer’s art (and why we need it now more than ever). Interspersed are scenes that allow us to enter Kiefer’s studio to get some inside perspective on how the artist goes about his creations, but these are also mainly interpretational. Outside of the occasional instance, we learn more about what Kiefer and his art stand for as opposed to who he is as a person; perhaps this was intentional to distance the artist from their art. This is an artist whose work has aimed to create transgressions of Germany’s past by using taboos to delegitimize the horrors of the Nazi regime; to this day, his use of a salute in “Heroic Symbols” is polarizing. Part of this is the mysteriousness surrounding the artist, and Wenders likely tried to keep this so: he allows audiences to wrestle with the weight and discomfort of Kiefer’s art as is intended.

Anselm uses most of its runtime to allow audiences to make their own connections with Anselm Kiefer’s art.

To represent Kiefer’s progressions as a person and an artist, the last act (if documentaries can even have “acts”) of Anselm is a bit of a deviation, with an actor playing a young Kiefer interacting with the real artist and his 2022 exhibition, Venice Cycle. My takeaway is that the world remains the same, yet people can grow if they wish to. The atrocities of old return periodically, and we must find it within ourselves to stop this. In the modern day and age where we still have Holocaust deniers (and the problem only seems to be getting worse through the detachment of the events through time and the influx of wrongful information being spewed and shared like a disease by the hateful), reminders like this are crucial. This is only one such reflection: the worst of humanity repeats itself. Kiefer’s art forces us to confront the darkest depths of civilization to encourage us to try and work our way back up; we cannot go any lower than this. Without the actual conveyance of such, there is hope in his art as a result: we find it within ourselves.

Wim Wenders’ latest documentary aims to achieve the same results. He doesn’t torture us. He instead opts for a brief ninety-minute runtime because he knows the severity of Anselm Kiefer’s art and the historical contexts attached will weigh heavily on us even in this short amount of time. With its 3D design, Anselm mirrors the barrenness of contemporary life with what feels like a post-apocalyptic future despite his art being representative of our past. If that doesn’t make you feel frozen in time, Wenders’ glacial, haunting pacing would feel like an episode of The Twilight Zone if there weren’t so many familiarities with the wars and political struggles that are going on in our world today. Anselm will most likely shake you, but if you are looking for a documentary to truly make you think and reflect (as most documentary aficionados expect), this latest Wenders effort will do the trick. Wenders allows the art to speak (mostly) for itself, which is sadly rare in the cinematic medium (where many filmmakers forget that film is also a visual art form, as they feel compelled to tell us everything). As was the case with Pina, I encourage the curious to seek this title out in its 3D presentations to get the full effect of what both Wenders and Kiefer intended for with this documentary: the stillness is impossible to ignore, and the power of the artwork here will give you goosebumps.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.