Ferrari

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

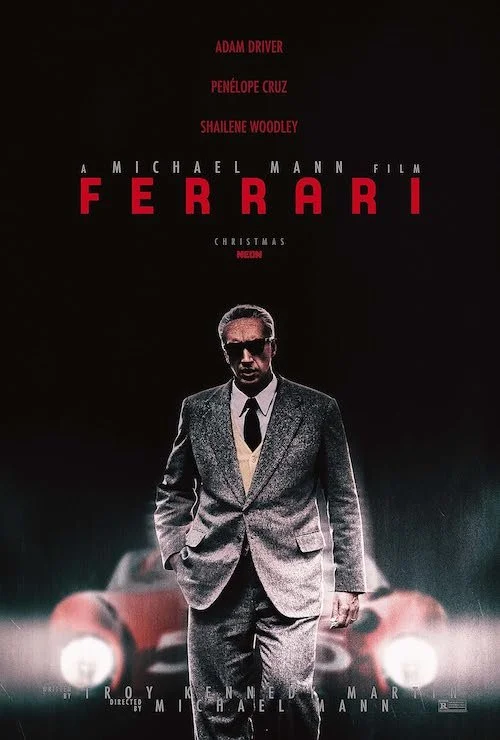

Even though I don’t think Michael Mann has made a great film since Collateral in 2004, I do feel like the acclaimed director has had something to say in each of his projects. Case in point: while I’m not the biggest fan of Miami Vice, the action film has garnered a cult fan base that swears that it is misunderstood. I don’t see this same army trying to persuade that the lukewarm reaction to Public Enemies is wrong, but in that same breath, I understand the John Dillinger picture to be equal parts flawed and refreshing; where I was disappointed in how botched the jail escape sequence felt, I was also gripped by Mann’s depiction of Dillinger’s relationship with Billie Frechette, and how she is both released from the curse of his crimes and damned by their love that was prematurely terminated. This leads us to his first film in eight years: the biographical picture Ferrari. With the audacity to cast Adam Driver after the vocal shit-show that is House of Gucci, it is clear that Mann saw something in this misdirected performance that could be refined for a film about the toughest year in Enzo Ferrari’s life. The screenplay is from the late Troy Kennedy Martin, who passed in 2009; this details the production pitfalls that Ferrari experienced for fifteen-plus years. Even with this in mind, the screenplay may be a little dated, but Ferrari, fortunately, doesn’t feel like the chaotic result of production hell. It isn’t perfect, but it’s also not anywhere close to being bad.

Instead of getting an entire study of Enzo Ferrari (Driver) as a person, we get a snippet in the form of the tumultuous summer of 1957. Ferrari S.p.A. is on the brink of bankruptcy. Enzo is unable to think clearly about this matter because of the death of his son Dino the year before; Enzo acted as his caregiver when he suffered from Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Enzo is at odds with his primary supporter, wife Laura Ferrari (Penélope Cruz), because of his affair with Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley); additionally, Laura doesn’t know that Lina’s child, whom Enzo is awfully tight with, is biologically his as well. Enzo is educating the science behind an engine’s power at one key sequence in the film. I am no mechanic so I will not get into the details the same way Enzo (and Driver, who is much better here than in Gucci) relay so effortlessly. Still, there’s the notion that power is generated by the pushing of air and fuel since they cannot exist in the same place at the same time. I bring this up because Ferrari as a film feels a lot like this: opposing forces that keep the film running despite the inability for all elements to work in harmony in Enzo’s life.

Ferrari feels a bit narratively slim, but its focus on one key year in Enzo Ferrari’s life is a wise choice.

All of this comes to a head in Enzo’s mind: he enters Scuderia Ferrari into the 1957 Mille Miglia to save his company, honour his late son (who was meant to follow in his footsteps), save his marriage, and give meaning to the name Enzo Ferrari. It seems like a bit of a tall order and a foolish dream, but Ferrari makes sure that this is the case so we understand the extra opposition Enzo faced while he was at his lowest. It is this focus on Enzo’s battle to save his life and everyone and everything in it that makes Ferrari as a film feel important. There aren’t too many racing moments in the film, but the ones that are few and far between are given all the more reason to exist and serve their thrilling purposes in the film; in fact, I am so glad that Ferrari didn’t rely on the racing sequences as a crutch. My major complaint is that I still think that the film is a little bit thin narratively. I wouldn’t call it too focused on this time in Enzo’s life, but the film could have afforded more time in general; this motion picture is only just over two hours. This film, with its style, ambition, and tension, screams “epic” everywhere outside of its story and runtime. I know audiences everywhere are crying for films to be shortened, but in this case, I think we needed just a bit more to turn Enzo Ferrari into the on-screen character that matches the mythology and stature of who he represents. Driver takes us most of the way there. We needed to reach that finish line.

Even though I feel like Ferrari roars and finally gets going at full speed around its third act and that the film is building towards a longer, fully realized picture, I do like what we get. We don’t learn too much about Enzo’s impact on the auto and racing industries, nor do we see the rise of the Ferrari family before the tragic fall, but we get what feels like a short story on the inability to take on everything and succeed in all places. Using Enzo Ferrari as the core subject for this statement is amusing because I do think that the people signing up for a typical biopic won’t get what they want. Even with the storytelling shortcomings, Ferrari is still far more interesting than what we could have gotten. It stomps on the gas pedal precisely when needed and dials things back when it needs to rest at the pit stop for a second and prepare for future sequences. You may not even feel the absence of the storytelling juice the film is missing because of the sleek pacing and focused tone of the film. Ferrari operates like a racecar that has been battered through one hundred laps; it isn’t always in the best shape, but it gets the job done and makes it to the end against all odds.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.