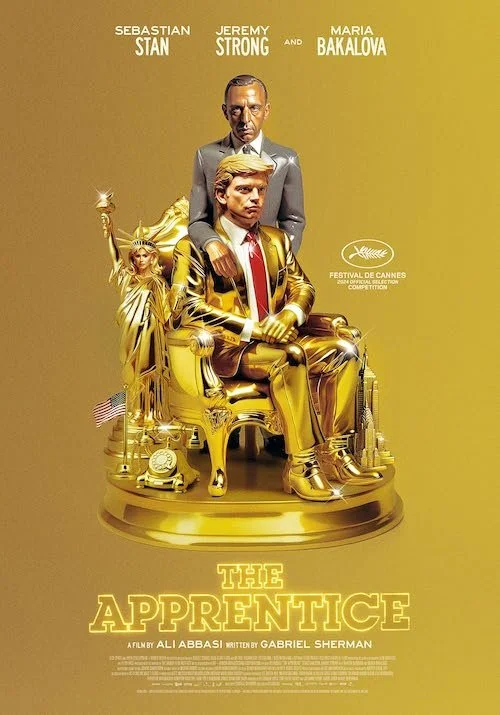

The Apprentice

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

I try not to get too political on Films Fatale; I believe there is a difference between stating your opinion and acting like either an adversary or opposer of platforms and representatives. However, with a film of this nature, I think it’s next to impossible to not have some shred of my political compass be revealed, but I will try my best to be as unbiased as possible when reviewing Iranian-Danish director Ali Abbasi’s English language debut, The Apprentice. In case you’ve been living under a rock (or Donald Trump’s efforts to scrub the world of this film have succeeded in your neck of the woods), this is a fable-like analysis of Donald Trump’s rise in power in a struggling New York City, all while under the guidance and purview of the equally tyrannical prosecutor, Roy Cohn.

We begin with President Richard Nixon infamously declaring that he is not a crook, which feels a bit on the nose at first until you get into the crux of what The Apprentice is trying to detail. An early scene has Cohn educating Trump on the three rules to win every single deal, debate, trial, or argument. First, you must “attack, attack, attack.” Secondly, “Admit nothing. Deny everything.” Lastly — and most importantly — even if you lose, you never admit defeat. You always claim victory. Throughout the film, we see Trump begin to implement this strategy to unfortunately great effect. We return to this opening piece of found footage: Nixon was only following step two. According to The Apprentice and both Cohn and Trump’s playbook, Nixon should have followed step three a little better; maybe he could have remained president with his clutches digging into the nation. Such is the self-absorption of a particular former president who refuses to accept defeat and continues to do whatever it takes to poison the well. Oops. Well, I tried, folks.

Before you go and write this film off as some super-liberal attempt to destroy Trump’s name, you’d be surprised to know that The Apprentice actually isn’t interested in making the biggest mockery of the mogul. Instead, it actually seems invested enough in trying to understand why Trump is the way that he is, via Abbasi’s demented depiction of the then-new version of the American family portrait and the nation’s dream. If we start off with the miasma surrounding Nixon’s term, we conclude in the eighties with Ronald Reagan’s rat race to the top of capitalist hill. Trump plays ball throughout both eras, seemingly naive and eager to learn at first, and with a corked bat towards the end of the film. “I don’t like deals. I love them,” Trump declares towards the end of the film, and The Apprentice showcases the figure anticipating the biggest deal he’s itching to make with the nation with a fairly obvious — yet well constructed — final shot. Throughout The Apprentice, Trump shrugs off the idea of ever becoming president despite the numerous suggestions that he should. We also see him progressively want more and more throughout the film; he will never be satisfied with what he has accomplished. He must be the biggest name in the history of civilization. Maybe he needed to reach a certain point of greed before becoming president was the next goal.

The Apprentice explores the reasons why Trump craves so much attention, power, and fame. Even though we don’t quite get a full version of a biographical picture, we get enough of one to understand that Trump was never extremely close with his father, real-estate figure Fred Trump. It’s implied that Fred Trump Jr. was the son who was favoured by both parents and the supposed next-in-line to take over the family business (hell, it’s evident even in the son’s name!). As Donald Trump (Sebastian Stan) was tasked with the menial work for the Trump real estate business (like having to chase after tenants for their late rent), he clearly dreams of higher aspirations. When seeking a legal representative for the Trumps, Donald comes across lawyer and prosecutor Roy Cohn (Jeremy Strong), who sees potential in the aspiring titan and starts to take him under his wing. Once Cohn delivers the three rules to always win, Trump is a changed man. He begins to dominate his industry and even his family before trying to see what else he can get away with. The sky is the limit for Trump, who eventually declares that the iconic Trump Tower — once initially constructed — could have been bigger than the World Trade Center had he really wanted to go that far (even though height doesn’t matter, he’s once again refusing “defeat” by only declaring himself a winner).

Jeremy Strong and Sebastian Stan are tremendous in The Apprentice: a film that begged for stretched caricatures but instead got performances that feel rooted in truth and reality.

Even though Trump gets worse and worse as a human being as the film goes on (I can’t even get into the monstrosities you’ll see, but I do warn you that the third act of the film is particularly triggering), it’s strange how easily Abbasi and company could have just turned The Apprentice into a guns-blazing onslaught on the former president’s character. Instead, The Apprentice feels genuine and sculpted enough to want to give people — yes, even Trump and Cohn — some sort of wiggle room to state their cases; they dig their own graves, mind you. In a film where Cohn winds up having a sympathetic angle — with Trump using the lawyer’s lessons to use against him, backstabbing his mentor during his darkest hour — you know Abbasi and screenwriter Gabriel Sherman prioritized the concern of how these people got here as opposed to the low-hanging-fruit approach of just shitting on these reputations as they currently stand. You can also tell, by this approach, that Cohn and Trump are the biggest reasons why they’re as hated as they are.

In fairness, with the film’s focus on reconstructing Trump’s descent into infamy and depravity, I think The Apprentice could have afforded just a bit of a longer runtime — even fifteen or twenty minutes — to place additional steps in this downward spiral so we never have to feel like we are leaping to the next point, especially since the film is trying to explain to Trump haters and convince Trump adorers of the extreme calculations that Trump took to get to where he is today. As a result, we do get a strong parable of greed and toxicity, but if you’re looking for concrete, dossier-like details of the most infamous man in contemporary American history, you may feel like The Apprentice doesn’t dig deep enough as a report (but most certainly as a character study, and definitely as a grave).

While the screenplay — which is quite well written from a dialogue standpoint — is not quite as full as it could have been, the rest of The Apprentice feels realized enough. The film is shot to feel a bit like we are within the seventies and eighties alongside Trump and his escapades. At times, we feel like we are in the same room watching these schemes and plans go down. Stan’s performance as Trump is — at times — spot on, with all of the mannerisms but enough restraint as to not have a full-on impersonation; he grounds his portrayal of one of the least grounded men in history. Maria Bakalova (best known for playing Borat’s daughter, Tutar, in the titular character’s sequel) is tremendous as Trump’s first wife, Ivana, even though I also wish she was in the film a bit longer. She understands Ivana’s similar passion for luxury and passion, while also fully channeling the darkest years of her relationship with Trump with maturity, seriousness, and both vulnerability and scorn (despite the brief screen time, Bakalova nails this part). The best performance of the film goes to Strong who is just as compelling as he is in Succession here, while also — somehow, miraculously — having us even care about Cohn during the last years of his life when he battled AIDS and its offshoot illnesses. With all three performances, The Apprentice is a study more than it is a satire or farce.

Even though it’s marginally disappointing that we don’t have the fullest picture possible, The Apprentice almost feels like Donald Trump himself got a hold of a bit of the film and encouraged the motion picture to, once again, deny everything, refuse defeat, and only be seen as a winner, warts and all. Since I understand Ali Abbasi’s angle to have an Aaron-Sorkin-like exemplum rather than a traditional biopic, The Apprentice mainly works as a cautionary tale of what too much greed looks like: zero satisfaction. Trump wins over Ivana and then reduces her to his fetish that he eventually rejects for the next fantasy. Prominence in the Trump family business isn’t enough; Donald Trump had to have a massive tower with the family name on it to show that he is better than his father. Trump had to repurpose Reagan’s slogan for his own eventual presidential campaign. Et cetera, et cetera. There are explanations throughout the film as to what ultimately broke Trump for good, including grief and pressure; we don’t get the proper answers as to why Trump is like this, but we get enough context for the film to work.

The real Donald Trump tried to sue the producers of The Apprentice into the ground so it could never see the light of day, but an online crowdfunding campaign met the marketing and distribution needs in what felt like hours. Despite the film’s perseverance to exist — and, unfortunately for the real Trump who foresees a straight-to-DVD fate for a film that’s actually really good — The Apprentice did not have to play by Trump and Cohn’s rules to succeed. It doesn’t only attack Trump; it attempts to figure him out. The Apprentice doesn’t admit nothing: it gets its hands dirty, while having enough authorial imprinting to remind you that this is a film and not a documentary. Finally, The Apprentice doesn’t actually claim that it has won over Donald Trump; it never feels like it is a holier-than-thou motion picture. As Roy Cohn watches his birthday cake — a massive American flag with sparklers gifted to him by Donald Trump — we see a different message than celebration alongside the prosecutor: we see a nation’s flag up in flames. If The Apprentice admits anything, it’s that — at the hands of one person’s quest to obtain as much power as possible in a nation that allows this corruption — we have all lost.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.