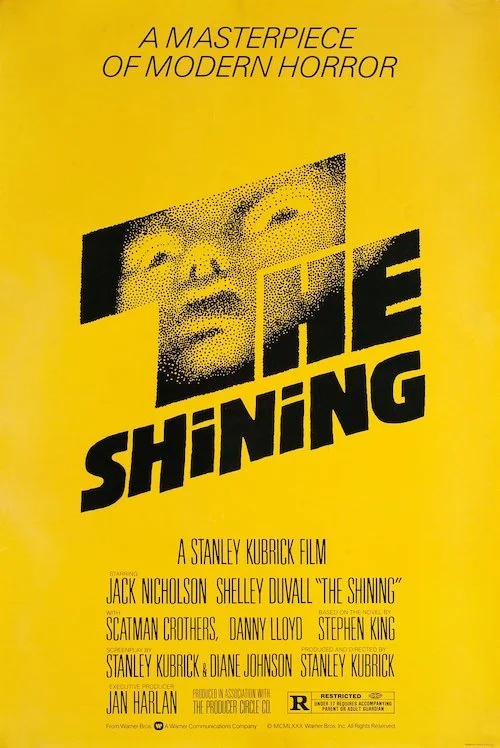

The Shining

Written by Octavio Carbajal González

Stanley Kubrick is widely regarded as one of the most visionary and influential directors in the history of cinema. His body of work spans diverse genres—from the science fiction of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and the historical drama of Barry Lyndon (1975) to the dystopian themes of violence and free will in A Clockwork Orange (1971), as well as the gritty realism of war in Full Metal Jacket (1987) and psychological explorations of powerful elites in Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Known for his meticulous attention to detail, technical innovation, and philosophical depth, Kubrick pushed the boundaries of storytelling and the language of cinema itself. He combined technical innovation with a profound understanding of thematic complexity, often blurring the lines between genres to create immersive and unforgettable experiences. His influence is seen across countless generations of filmmakers, from Christopher Nolan to David Lynch, who once said, “Kubrick is one of the best filmmakers ever. It was Kubrick who freed me, made me see there are absolutely no rules.”

Released in 1980, The Shining was Kubrick's foray into psychological horror, an adaptation of Stephen King’s best-selling novel. At the time of its release, the film polarized critics and audiences alike, with some decrying its deviation from King’s original narrative and others praising its atmospheric tension and visual mastery. Over time, The Shining has cemented itself as one of Kubrick’s most iconic works, hailed for its unsettling blend of psychological horror, supernatural elements, and complex family dynamics. Integral to the haunting atmosphere of The Shining is also its evocative soundtrack, which combines classical compositions with avant-garde pieces. From the eerie synthesizer rendition of “Dies Irae” that opens the film to the unsettling dissonance of works by composers like Béla Bartók and György Ligeti, the music becomes a character in its own right. Kubrick’s innovative use of sound and silence, along with his signature visual style, work in tandem to create a horrific immersive experience.

As Jack, Wendy, and Danny Torrance arrive at the isolated Overlook Hotel, the vast, eerie setting foreshadows the psychological horrors that will soon unravel.

From the very first scene, Kubrick makes his intentions clear. Wrapped in an unsettling atmosphere, the camera steadily tracks a small car driving towards the Overlook hotel. What follows is a seemingly mundane meeting between the hotel manager and writer Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson), who has been hired as the caretaker during the hotel’s winter closure. The manager cautiously warns Jack that the hotel can become completely isolated from the outside world during heavy snowfalls, even mentioning a tragic incident involving a previous caretaker. Jack reassures the manager that he and his family will be fine. We also learn about Jack’s wife, Wendy (Shelley Duvall), and their young son Danny (Danny Lloyd), who possesses an imaginary friend called Tony, and a mysterious psychic ability called “the shining”.

During a later conversation with a doctor, Wendy casually reveals Jack’s struggle with alcoholism, a flaw that led to a traumatic event for both her and Danny in the past. Once Jack and his family move into the Overlook Hotel, the film begins to emphasize the vastness of the space. With the hotel now empty after its closure, the camera follows the family through its disturbing interiors. At times, it seems there’s no way out, a feeling intensified when the camera ominously watches Wendy and Danny wandering through the hedge maze outside the hotel. Later on, Jack starts his descend into madness, and the audience starts to rely more on Wendy and Danny’s perspectives. Yet, neither of them is entirely trustworthy, as they too begin to unravel psychologically.

After a terrifying experience in one of the hotel rooms, Danny becomes increasingly disturbed, and his frightening visions start to materialize. Wendy, on the other hand, tries desperately to maintain control, but eventually finds herself overwhelmed by fear and confusion. Kubrick maintains a cold and detached tone, as he often does in his films, making the horror feel even more intense. The characters may seem exaggerated, but their descent into insanity remains captivating due to the overwhelming sense of claustrophobia. Separated from one another, they lose their sense of humanity (a deliberate choice by Kubrick that likely explains why he pushed his actors to such extreme performances). Nicholson embraces his manic energy, while Shelley Duvall’s portrayal of Wendy’s fragile mental state reaches intense peaks.

Danny wanders the seemingly endless halls of the Overlook Hotel, with Kubrick’s meticulous direction turning the hotel into a maze of creeping dread and psychological tension.

Classical psychoanalytic thought heavily focused on the pathologies that arise within dysfunctional families. In this context, the claustrophobic environment of The Overlook Hotel symbolizes a dysfunctional household ruled by a tyrannical father figure, who holds power over a helpless mother and child. The spirits that dominate The Overlook represent the projections of the characters’ fears and dysfunctions. Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud described projection as a defense mechanism intended to protect the individual from psychological harm by externalizing internal conflicts: “Projection is a form of defense in which unwanted feelings are displaced onto another person, where they then appear as a threat from the external world. A common form of projection occurs when an individual, threatened by his own angry feelings, accuses another of harboring hostile thoughts”. This defense mechanism is most clearly seen in Jack’s interactions with the ghosts of the film, but it also operates to a lesser extent in Wendy and Danny. Jack’s violent impulses, rage, and cold, calculating thoughts are too overwhelming for him to confront, so he projects them onto his environment to shield his psyche from the full weight of his own pathology. “The shadow” theory of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung is also essential to understanding Jack’s character. The shadow, which encapsulates all repressed and socially unacceptable desires, becomes a potent force within Jack as he succumbs to the Overlook’s influence.

Danny, on the other hand, represents an alternative psychological journey. His psychic ability, “the shining,” can be viewed as a metaphor for heightened sensitivity to the unconscious forces at play in the hotel. Danny is not only a victim of Jack’s violence but also an innocent child trying to make sense of the dark forces surrounding him. His imaginary friend, Tony, can be seen as a manifestation of his own psyche, a defense mechanism that attempts to shield him from the horrors both within his family and within the Overlook itself. Danny’s journey is one of survival and psychological resilience. Where Jack succumbs to his shadow, Danny is able to confront and outmaneuver the forces that threaten him.

On a sociological level, The Shining can be read as a critique of patriarchal power dynamics and the violence inherent in traditional family structures. Jack’s role as the patriarch of the family is one defined by control, dominance, and authority—traits that, when exacerbated by the Overlook’s influence, turn into violent and oppressive behaviors. The film highlights the dangers of unchecked male power within the family, where Jack’s frustrations and failures in his professional life are channeled into abusive tendencies toward his wife and son. This situation echoes the analysis of German-American psychoanalyst Erich Fromm’s destructive behavior as a response to powerlessness in his book The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness (1973). Jack's perceived failures as a provider and a writer make him lash out against the very family he is supposed to protect.

The unforgettable 'Here’s Johnny!' scene captures Jack Torrance in the midst of his descent into madness, an image etched in the history of horror cinema.

Wendy, meanwhile, is depicted as the submissive, nurturing mother figure, trapped in the domestic space of the hotel and subject to Jack’s increasing aggression. Her struggle to protect Danny while also maintaining some semblance of normalcy within the family reflects the challenges faced by women in patriarchal family systems.Wendy’s journey in the film can be viewed as a struggle for survival in a situation where the odds are overwhelmingly stacked against her. She is isolated, cut off from any external help, and must protect her son from both Jack and the hotel’s supernatural forces. Wendy’s character is also significant from a feminist perspective. While she initially fits the mold of the “hysterical woman” often portrayed in horror films, her actions throughout The Shining reveal a deeper complexity. Wendy’s emotional breakdowns, far from being signs of weakness, are expressions of the immense psychological pressure she endures. Kubrick puts Wendy in a position where she must face both psychological terror and physical danger, and yet she perseveres. Her strength is not defined by aggression or physical power but by her capacity to endure and protect her son in the face of unimaginable horror.

The Overlook Hotel’s labyrinthine design, especially the hedge maze, serves as a philosophical metaphor for the existential challenges faced by the characters. The maze symbolizes the human mind, filled with dead ends, contradictions, and complexities that are difficult to navigate. The maze, like life itself, offers no easy answers, and Jack’s inability to find his way out is emblematic of his inability to find meaning or redemption in his own existence.

Ultimately, The Shining leaves audiences with more questions than answers, challenging them to consider the nature of evil—both external and internal—and the impact of isolation on the human spirit. Its ambiguous ending reinforces the idea that the horrors of the Overlook Hotel may linger long after the credits roll, haunting not only the characters within the story but also the viewers who dare to enter its chilling world. Kubrick’s legacy endures through this film, a testament to his ability to fuse unsettling visuals with profound psychological insight, making The Shining a timeless classic that continues to provoke thought and discussion.

Octavio is a passionate cinema enthusiast from Mexico City, he mostly enjoys watching arthouse films from all over the globe. His reviews are published on "Vinyl Writers" (www.vinylwriters.com).