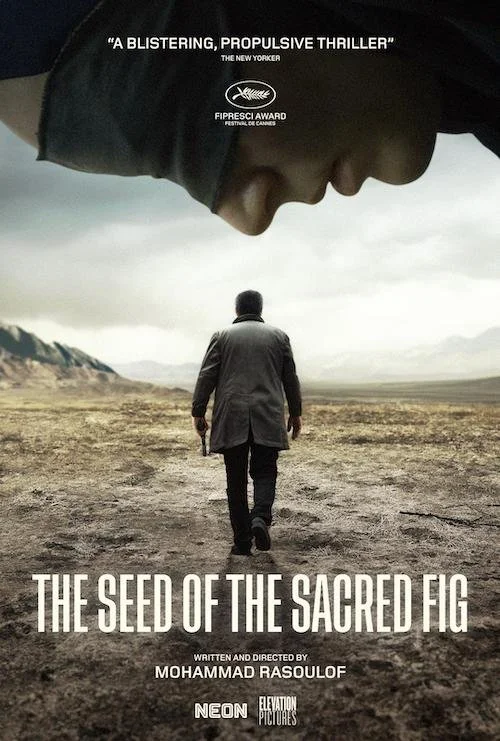

The Seed of the Sacred Fig

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: This review contains minor spoilers for The Seed of the Sacred Fig. Reader discretion is advised.

We cannot escape the overwhelming sense of doom that is happening on a universal scale. That couldn’t be more true for Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof. Rasoulof was arrested back in 2022 for voicing his opinion on the Iranian government’s methods of handling the collapse of the Metropol building. While released, Rasoulof was still forbidden from leaving Iran for two years. Due to this extreme scrutiny of his every move, the government subsequently tried to stop Rasoulof from releasing his latest film, The Seed of the Sacred Fig, with efforts to force him to pull the film from the 2024 Cannes Film Festival, threatening to contain him for even longer in Iran, and harassing him and his cast and crew. Ultimately, since Rasoulof refused to pull his film from the festival, he was sentenced to eight years in prison, flogging, and the seizing of his property. Rasoulof spent nearly a month trying to escape Iran, eventually succeeding and winding up in Europe, likely unable to ever return to his homeland.

What were Iranian authorities trying to hide? The Seed of the Sacred Fig begins with deadcard text stating how plants — including the titular sacred fig — are created by the spreading of their seeds, through weather-based means or the excrement of the birds who eat these seed-bearing fruits and vegetables. The sacred fig is known to wrap around other trees and strangle them. The title of the film implies the life or hope spawned through the times of violence, but we get a different metaphor right away. The first image we see contains small bullets, clattering on a table, as if these are the seeds of the new age. These cause death instead of life, as it is not a litter of offspring that spreads but rather the blood of the innocent across the floors and walls of society.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig grips you from the first shot and never lets go.

The film has a unique take on plot development that may not sit well for all viewers, but it’s one I found highly effective. The first hour is about setting the scene before we actually get to the major crux of the film roughly halfway through the motion picture. It is a gamble that pays off given Rasoulof’s reason for taking this risk. The first hour is dedicated towards the perils of doomscrolling, as we find members of the central family watching the nationwide Iranian protests on their phones. The Seed of the Sacred Fig cuts to these videos, which take up the entire shot for long-enough periods of time, as we hop from one demonstration or shot of authoritative brutality to the next. These are real videos, not ones constructed for the film. Rasoulof sets the tone with graphic images we cannot ignore: a very real look at why the director is angry with his nation’s authorities. In the meantime, the patriarch of the family, Iman (Missagh Zareh) has been appointed the role of investigating judge at the Islamic Revolutionary Court. He first sees this as an upgrade, given the salary and the implication that he must have been qualified because of his strengths. He quickly finds out that he is meant to just blindly permit major penalties and sentences, including executions, and it’s likely that he was hired because he is seen as someone who couldn’t stand up against authority, so these sentences can be carried out as intended.

As tensions worsen and paranoia hits Iman and his family for different reasons (Iman is leading a guilty life that can hurt him and his loved ones if he is compromised, while his family fears for their safety given the current state of Iran), we finally get to the plot point that kicks things in motion. Iman is given a gun by the government in case he or his family needs it. This gun suddenly goes missing. Not only does Iman panic, since this could land him in hot water with the Iranian government, but he begins to suspect members of his family, who are all women and have been keeping up with the ongoing Girls of Enghelab protests (ones that question the compulsory wearing of a hijab). Despite taking the job of investigating judge to have better living conditions and wealth for his family, he begins to turn on his wife and daughters, placing them in various interrogations to find out if anyone stole his gun. This suspicion only worsens, and the central family becomes a fascinating mirror of Iran itself, as we see a father and husband who vowed to protect, trust, and love his family now treat them like criminals and vermin. Even though we’re no longer viewing real footage of destruction and bloodshed in the streets of Tehran, we’re still seeing Rasoulof’s scathing perception of Iran: a beautiful place being sabotaged by corruption and lies. Iman is the sacred fig: the plant that clung onto his family and is slowly strangling his loved ones.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig is a slow burn that takes its time to reveal its true story, but once it does, it becomes an unforgettable thriller that will haunt you.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig is a slow burn that has purpose for its pacing. Once it picks up steam, it becomes one of the most haunting films of the year: an unapologetic look at smothering authority and the anxiety-ridden loss of control that authoritative figures can experience. Much to the chagrin of the Iranian government, The Seed of the Sacred Fig becomes an instant hit in Iranian cinema that fits in nicely with Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation or Majid Majidi’s Children of Heaven: love letters to the people, cinema, and culture of Iran while being unsupportive of what the government has done to its citizens. The Seed of the Sacred Fig moves at a slow pace because no battle is short. Mohammad Rasoulof’s brilliant film understands what perseverance looks like, and he proves that he is a master of filmmaking with a motion picture that has patience and knows when to strike. Between the film’s blistering climax (a lengthy, thrilling look at the art of survival and escape) and its ending shots, The Seed of the Sacred Fig is magnificently tied together by its talking points in ways I’ll allow the film to reveal to you. We finally understand the film’s title as well: the resilience stemmed from a political stranglehold. The Seed of the Sacred Fig is a monumental release that has to be seen to be believed.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.