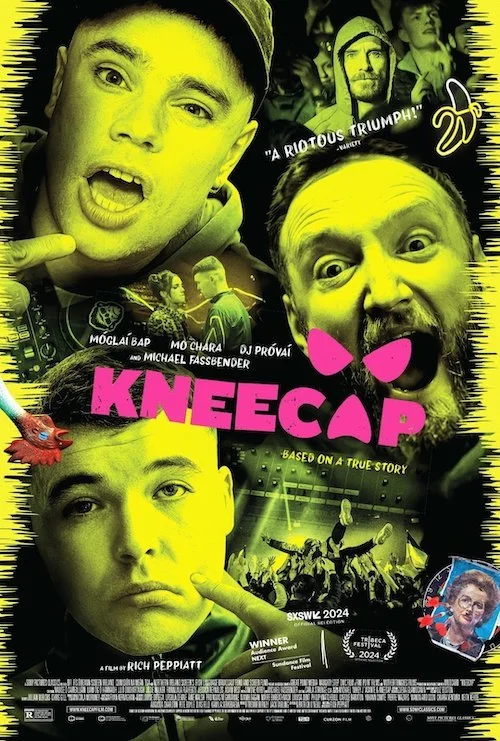

Kneecap

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

For those who are not aficionados of hip hop, it can be difficult to separate the rapper from their words. Artists pepper hyperbole throughout their songs all the time. Much of hip hop comes from a place of truth as well, as it can depict one’s upbringing, struggles, or current predicaments and beef (if 2024’s never-ending feud between Kendrick Lamar and Drake is any indication). How do you separate the real from the fictional? How do you know when a song is about a character being portrayed, and when these lyrics pertain to the rappers themselves? Kneecap is a pseudo-biopic about the titular, Irish hip hop trio: a film that tells their rise to fame as much as it tosses in ingredients to spice up this dish. Whether this is the “authentic” Kneecap story or the embellished one (I’m not even sure what parts to take out as truth and what to disregard as exaggeration) doesn’t matter. This is still a fun and energetic comedy-drama about music, the streets of Belfast, and the Northern Ireland peace process stemming from the previous Troubles: there’s enough truth here, even if it isn’t explicitly Kneecap’s.

We follow the three members (Mo Chara, Móglaí Bap, and DJ Próvaí) and Kneecap’s origin story. Instead of just settling for a bare-basics approach, Kneecap gets a little intricate with how this group came to be (well, in director Rich Peppiatt’s version), incorporating much of Ireland’s sociopolitical issues of then (the early 2010s) and now, from police brutality to the disappearance of and scoffing against the traditional Irish language (cleverly used to represent how today’s generations don’t have a voice, or are encouraged to not speak up). The three chaps have different backgrounds; Móglaí Bap’s father, Arlo (Michael Fassbender) is a former paramilitary on the lam since faking his own death to get away from British authorities. DJ Próvaí is a teacher who does not want to be discovered via Kneecap’s music (as to not lose his job), so he dons a skimask to obscure his identity. Mo Chara cannot stop getting into trouble with the law, even for reasons beyond his control. Together, they find unity and harmony within Kneecap, but their problems don’t vanish, including rising tensions surrounding the band’s existence and the media’s spin on their purpose (instead of highlighting the suffering of Northern Ireland’s citizens, they’re made out to be bad influences).

Kneecap is a unique way to tell both the story of a band and their host nation’s history and current political divide.

Kneecap is a bit of a curious film, because it feels like two separate entities: a motion picture that doesn’t play by the rules, and your typical biopic that does. On one hand, there are animations on screen that tell additional information in refreshing ways. On the other, Kneecap hits every expected point plot wise in a way that kind of softens what we see. Even though Kneecap is a mish-mash of reality and expressionism, it’s also quite conventional; this doesn’t tarnish the experiment, but it doesn’t really strengthen it, either. Kneecap is a solid, hilarious, fresh take on how music, musicians, and musical representation of politics can be interpreted on the big screen. It feels like it is itching to get even more unorthodox than it already is, but, in that same breath, if one of Kneecap’s purposes — according to this film — was to revitalize the Irish language for the youths of today, maybe they were always aiming for applicability. On that note, Kneecap is an easy film to watch, in case you’re worried about its abrasiveness (it’s hardly so). Expect a riot, but in the sense that Kneecap is quite a hoot to watch as well; it’s as much a celebration as it is a statement.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.