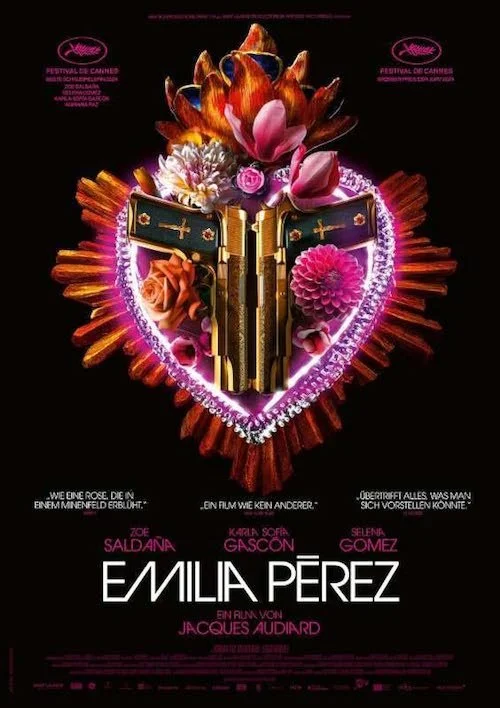

Emilia Pérez Revisited

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Note: We reviewed Emilia Pérez once before, here, which we are revisiting with a new perspective after half a year of many shifts and turns in the film’s legacy: one that was once cherished but has now been grossly tarnished.

I usually don’t revisit films I’ve already covered on Films Fatale, unless I am writing a Best Picture review for an Oscar winner I’ve previously reviewed (a tradition I have), let alone a motion picture that is only half a year old. I don’t want to indicate any flimsiness of how I review films, because I am someone who is always certain of how I feel about a release when I first watch it. I also do not intend on insisting that the opinions of others have made me feel differently about a film because I will always march to the beat of my own drum; I am aware that I frequently agree with general consensus, but I will die on hills of hot takes when they should arise (I’ll leave those opinions for when they are necessary; I want to focus on the topic at hand here). In short, I am someone who is comfortable with my own takes on films and always have been. I am not easily swayed. I am not paid for my views, nor am I sponsored to make content. I serve no one but myself.

So, why am I revisiting Emilia Pérez, and why do I like it less only six months after I first saw it?

This is my opportunity to explain.

I don’t believe in deleting old reviews in any way, even if there was ever a cause for me to rethink something I previously wrote (I always expected this day would come, but I never thought it would be this soon). With that in mind, I am not going to delete my previous review, which can be found in the link above in the header, because I believe in complete transparency; the review can be used as a bookmark for how I was feeling at that very time, and to eliminate it feels like shame, dishonesty, and uncertainty via the act of redacting. I do not subscribe to these forms of gaslighting, censorship, and egotism. However, should I feel differently about a film, I do think it’s important to best represent myself and how I am feeling in the present.

I honestly don’t care about the artist if they are problematic when I am viewing art, because I separate the creator from their creation. Always. My rule of thumb is if someone I one liked has been revealed to be a terrible person, I will never lose the connection I had with their work previously (like, say, Kanye West with everything from The Life of Pablo and before), but I will never support their works to come (I can gladly say I haven’t listened to a new West release in years, because, to put it politely, fuck him). To me, I have formed a bond with the work in a way that speaks to me, and my reviews are the act of channeling what that call-and-response between the art and the recipient (via the experience I have) is. Personal drama is all background noise, and I want to focus just on what was gestated, not who made it. If one’s sins are bad enough to be impossible to ignore, I can choose to never support them again, which I frequently do (I’ll likely never review a new Kevin Spacey film, especially if he is the lead; I don’t care how many clicks I’d get out of covering his work). In short, how someone lives their lives usually won’t affect my ratings or reviews. If a terrible film was made by good people, or if a great film was made by adulterers, catty personalities, or compulsive liars. Again, if we’re talking about complete monsters, that’s a bit of a different story, and I’d never support them as individuals.

Let’s not tiptoe anymore. Why did I dock Emilia Pérez a full star?

Because I fell out of love with the film.

This is going to be a bit of a different review, one with multiple parts, including what I originally saw (in short), how I saw it, and why this experience would read differently to the majority of people who saw Emilia Pérez. I will then go into what changed for me and why.

What Once Was

At the Toronto International Film Festival 2024, I was privileged enough to see Emilia Pérez’s second screening. Zoe Saldaña and Karla Sofía Gascón were both in attendance; Selena Gomez left the day before, but attended the North American premiere. At the Princess of Wales theatre in Toronto, it was a packed house at nine thirty in the morning. The room had a buzz to it. I can differentiate when I feel like I disagree with the general consensus of a room, and I’ve certainly been to a TIFF screening where other people were having a great time, while I wanted to eat glass and put an end to it all because of how much I hated the film. I’ve also been a part of screenings I have loved that others were not feeling whatsoever (I will stand by the claim that Brian De Palma’s Passion is a grossly misunderstood satire that is worth a chance, and my screening of it was highly uncomfortable with how much energy was sucked out of that room). I genuinely liked Emilia Pérez when I first saw it. The room was laughing alongside the majority of jokes, and I was on the same page with that crowd. On the big screen, the vibrant, audacious musical numbers and tone all hit differently. It feels like an injection of pure adrenaline.

I saw a film that was equal parts crime drama, dark comedy (with a hint of absurdist sensibility), and sugary musical. I felt like this was a bold genre-bender that was unapologetically its own film. I wasn’t oblivious to the most obvious flaws of the film, like that incredibly awkward “penis-to-vagina” song (I was on guard for any similar songs to appear, but, fortunately, they didn’t, and this extreme moment was an anomaly early into the film). However, I was willing to forgive them because of all of the things that seemed to work for me, including the stars leaving everything on the floor, Emilia Pérez’s dedication to upholding each of its genres at all times, and the experience of seeing a film try to be one thing and unable to escape its other self.

After the film, I know I wasn’t the only person feeling this way because the whole auditorium took part in the longest standing ovation that I have personally seen at any TIFF. It was well over five minutes, maybe even closer to seven or eight minutes in length; it was so long that Saldaña had to turn away from how emotional she got, and Gascón insisted that we finally sit because she was beginning to not be able to handle how much love they received either. The Q&A after the film went really well, with no hints of malice or poor taste or intention. For the rest of that morning, the hundreds of people at that screening couldn’t stop gushing about Emilia Pérez. It was the talk of the town. The film came second at the People’s Choice Awards at TIFF, so it was clearly a highly popular release. I’m not trying to excuse my state of mind or justify me liking what is now a highly maligned film, but you do have to understand that there was a point in time when Emilia Pérez was actually adored. The film had multiple actresses win a shared acting award at Cannes, for crying out loud. It was instantly discussed as one of the top films of the year by many, including myself, and its boldness was both evident and respected.

You can feel free to read my original review to see my initial insights in more depth; I don’t feel like I should be reiterating them here when the points have already been made.

So, what changed with society? What changed with me?

Why Society Likes Emilia Pérez Less

The issues started shortly after Emilia Pérez was released on Netflix after a very brief, limited theatrical run (I work for the TIFF LightBox, and I can guarantee that our two-week run of the film was met with the usual responses: some people loved the film, some didn’t quite vibe with it, and others hated it; nothing unusual to report here). On social media, some early parts of the film were shown out of context and it looked awful in this way (that penis-to-vagina song wasn’t doing the film any favours). However, it was once the Golden Globes happened this year and Emilia Pérez won over the likes of Wicked that the disdain really kicked off. I am not going to be blaming the Wicked fan base, nor will I be critical of pop aficionados, but the evidence is clear that these circles are mighty and large. The amount of Wicked fans who were furious that a messier, louder, and uglier film (qualities I once loved regarding Emilia Pérez: if done correctly, chaos and roughness can add an identity to a film) beat a beloved adaptation of a Broadway staple was massive. There was also a pitting of women together, which happens far too often within the pop music industry; fans of Arianna Grande and Selena Gomez were at each others’ throats, insinuating that the former’s nomination is proof that the latter is a terrible star, for instance.

Then started the smear campaigns began, with the kind of social media deep-diving that has sadly become customary for chronically online citizens who must win an argument with faceless strangers sharing the same ones and zeros via an app. This led to the surfacing of Gascón’s hideous tweets from her now-deactivated Twitter account. A legitimate reason for people to boycott the film, Gascón’s awful takes on Muslims, Jews, Black people, the LGBTQ+ community (possibly the biggest shocker to me, considering that Gascón has made waves as the most awarded trans actress of all time for Emilia Pérez), and even the Academy Awards themselves (which Gascón heavily criticized) and co-star Gomez, are, like the vibrant style of Emilia Pérez as a film, impossible to dismiss. I cannot fault people for feeling this way. I remember that TIFF morning, seeing this star that I was so proud of and was ready to champion during the award season (I was certain that Gascón was going to be a force to be reckoned with, and was correct). I saw someone lovely and delightful. I didn’t know that she was capable of such hate and misery. These revelations have marred my memory. I won’t rate her performance any less because of who she is, but I unquestionably have no respect for Gascón anymore; I don’t care how special that screening was.

This backlash led to director Jacques Audiard, who has released many great films before (his magnum opus A Prophet, the Palme d’Or winning Dheepan, Rust and Bone, and many more), being the next talking point. Audiard, I suppose in response to Gascón’s situation (and, also, before these tweets resurfaced), was promoting the film. By this point, he was getting hit with some hard hitting questions, and I will touch upon the reason why shortly. Audiard essentially admitted that he put little work into studying the subject matters of his film, suggesting that, since Emilia Pérez is an opera, that truthfulness wasn’t important. I can understand that point to a degree: art is art, and it is not always meant to be a complete recreation of reality. Having said that, when you are telling a story of a different nation, I think respect has to be earned. Additionally, Audiard likening Latin citizens as lower-class people (he essentially said that Spanish is the language of the poor) is a horrible look, which I will be getting more into in the next section. He did Emilia Pérez no favours. As someone who has loved his genre-bending works in the past and still do, I cannot help but wonder what the hell his thought process was during this press circuit. I know he is older and likely doesn’t care anymore, but legacy is everything. In fact, legacy is a major theme of Emilia Pérez. Does Audiard want to be remembered as a bigot? He’s essentially heading in that direction.

On the topic of the representation of Mexico and the use of the Spanish language, Emilia Pérez came under fire once more people had access to it. Once more native Spanish-speakers and Mexican viewers came across it, the representation of the nation — alongside the clunky Spanish dialogue — were skewered. What doesn’t help is that Netflix held off on releasing Emilia Pérez to users in Mexico for months, which to me — and many others — shows at least a hint of guilt; why wouldn’t Mexico be the first place that Emilia Pérez is released to if it is meant to be a celebration of Mexican culture? What Netflix’s strategy looks like instead is damage control: an admittance of a problem (to prove this point, consider how Gascón, who plays the titular main character, has been scrubbed of all new posters, showcasing Netflix’s awareness of the toxic discourse surrounding the central star).

Additionally, watching the film on a far-smaller screen via Netflix alone (either via my television or my laptop) isn’t nearly the same experience as seeing it on a far larger scale with hundreds of other people; maybe this film was meant to be seen in such an environment, but being an instant Netflix release somewhat banishes the film to the instant fate of sole judgement: one viewer not sharing this film with anyone else, and having the size, boldness, and ideas of such a film diminished. Of course, this can be true with any such film, but I bring this up because Emilia Pérez wasn’t nearly as hated as it is now when it is so widely available via Netflix; during its brief festival and theatrical runs, the film garnered quite a bit of love. I’m not saying that this is the sole reason for the film’s downfall, but — amidst everything else — I suppose such a concern doesn’t help, either.

What seems to have started as a campaign from one fandom to besmirch another has led to a series of legitimate accusations and points. It’s obvious how different the response from the film festival scene has been from the rest of the world. There are many films that aren’t going to be everyone’s cup of tea; a film like Titane can be deemed brilliant via festival audiences, and then prove to be too much for common film goers. However, Emilia Pérez feels different. This isn’t a question of differentiating one audience from another, but, rather, noting that Emilia Pérez’s reputation has drastically changed so quickly, and that the same people who first experienced the film may now feel differently; this includes myself.

Why I Like Emilia Pérez Less

I won’t be persuaded by other peoples’ opinions, but I am always open to hearing and understanding other viewpoints. Maybe I missed something in a film that someone else saw. I cannot profess to having a proper perspective of what Mexico is like outside of the resorts I have visited and the landmarks I have soaked in (this is a privilege, I know), but I am willing to believe others when they say that Emilia Pérez does a terrible job at representing the country. I don’t view Emilia Pérez as an indication of what all things Mexico are like, but rather a narrow look at this particular story of a drug cartel lord who is both evading her own demise and wanting to transition. I never once felt like this film is what Mexico is like through and through. What I once saw was an honest attempt by an outsider from France to try and depict a crime film within the confines of a different nation.

However, after Audiard’s comments, all I can see how is someone who views the country as a pitiful one full of desperate people. I see characters written and directed in a way that indicates that these are sorry, pathetic people who should be cried for because they as an entire community are as low as humanity gets. To me, this feels like exploitation. Audiard and company adapted this French tale into a Mexican one for the reasons covered above, and his claims show an intent to me; you don’t just change a setting and the nationality of characters for no reason. Therefore, I cannot watch Emilia Pérez and feel my original depictions of tragedy with an everyday person (Saldaña’s character, the lawyer Rita) getting caught up in the criminal underworld. I instead see nothing but ill-guided sympathy from someone who doesn’t even know anything about those he aims to sympathize. In this instance, I can still separate the artist from the art, but not the art from the artist; I know what his points are now, and they’ve changed how I read the film.

I’m also learning Spanish, ever since November. I noticed it was the one language I retained a few words from over ten years ago when I was learning it for two weeks, and wanted to see how well I could learn the language. I am no where near fluent by any means in just four months, but, as I had hoped, I am picking up on some basic words and phrases just by listening. With that in mind, with the little I can ascertain from Emilia Pérez now, I can agree that even from the little Spanish I know that things feel off with the dialogue in this film. I can’t speak to how rough Gomes’ Spanish is (especially since her character is meant to be an American who moved to Mexico and learned Spanish later, which is a tidbit many often forget to bring up when criticizing the film), but I can say that there are enough points in the film that the dialogue at least feels basic, stiff, or unfinished. I cannot unhear this, and — should I stick with my Spanish lessons — I can only imagine that the dialogue will feel worse and worse with time.

I think my new perspective on the film and the inability to bypass the rudimentary Spanish dialogue makes it harder to forgive the flaws I originally saw. The doctor who only has one song but came off as a sincere-but-weak singer? He now feels more prominent as a blemish amongst blemishes. The song about the son smelling his dead father’s presence while Emilia Pérez is in the room? I once felt like this was a well-intended attempt to link these characters together, but I now feel like Audiard doesn’t understand what transitioning is like for many trans viewers, and this song feels tone-deaf. I don’t even need to explain the lowest point (the penis-to-vagina song) yet again. The boldness that once was now feels a little sugary and abrasive unapologetically, not with a vision and purpose. Characters feel less rounded now that I sense their purpose as conveyors of guilt and tears. I can’t get as lost in the songs now that every other verse will hit me with an awkward phrasing that now feels like a ton of bricks.

However, I won’t pretend to outright loathe the film like so many are just because it’s popular. I still see the quite-strong performance by Gascón despite her awful personality, and my heart bleeds for Saldaña who I still think is stellar with possibly her best acting to date (maybe especially so since I now think less highly of the script and direction she had to work with). I still feel like some of the songs are well composed and whisk me away. I think that many complaints stem from a lack of media literacy (I will never agree that Emilia Pérez paints the title character as a saint post transition, especially when she is frequently framed with angles, lighting, and cuts meant to evoke fear), common film-goers watching a film that is meant for a different crowd (sure, some of the dialogue, even in English, can come off as brash and ironically funny, but I do think that some of the moments misconceived as so-bad-it’s-good were meant to be funny already, maybe for a European or non-conventional audience), or those who want so badly to be a part of the shit-posting zeitgeist (no, the “Bienvenida” song didn’t use the wrong translation of “welcome” like many are leading you to believe).

I still see a film that is lively, electrifying, and intentionally acrimonious. I feel the pulse of this feature. I get emotional for Saldaña’s character, Rita, throughout the film. I sense the film’s transition from a gritty, dark, cynical look at the world to a musically hopeful perspective of tomorrow. I laugh along with the film’s strange sense of humour that many have been quick to label as moments of seriousness that didn’t work (I disagree, for the most part). With that in mind, I have reduced my score from a 4.5 out of 5 to a 3.5: a designation that I still think the film is good but far more flawed than I once felt. I also think there are people out there who would like the film should they ever stumble upon it (perhaps not now given the vitriol that continues to permeate). I cannot condemn an entire cast and crew over the toxicity of a few people involved, but I also cannot shake off the key revelations that change how the film reads; in the same way that a director’s interviews can give me a new, better perspective on their work, I suppose the opposite is true as well. In the very way that I cannot betray myself and what I am honestly thinking (with what I like about the film), I cannot ignore what has made me feel differently about Emilia Pérez.

I will keep the original review posted for the reasons stated above, but I also want it to be an indication of how cinema can be an experience and not just an artform. That review details my first experience with Emilia Pérez: one that I can never forget. This review now provides an update on how I now feel about the film. I will also be amending my best-of lists including Emilia Pérez, because I cannot in good conscience leave a film that I feel less favourable of on lists that I want to provide my true feelings of what the highest caliber works of late are. Will I ever like the film a little more again? Maybe. I am forever evolving, and so is my taste. With that same breath, could I ever like the film even less as I grow old? Sure. The main question that remains is if I will ever love Emilia Pérez again. Given all that I have stated, probably not.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.