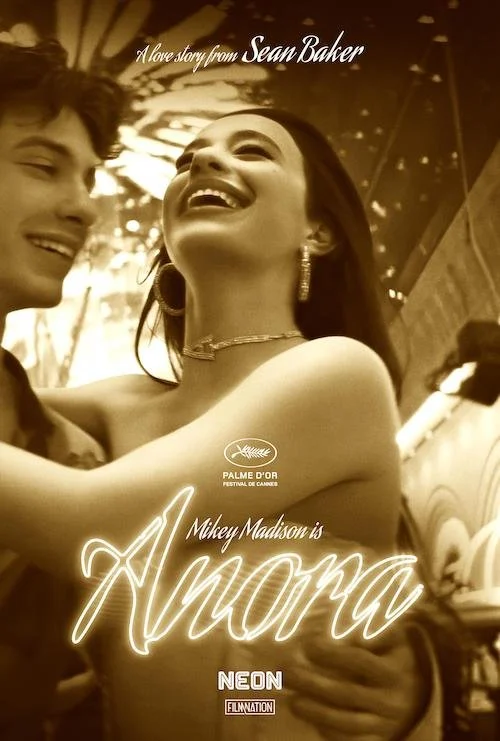

Anora

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Anora is the ninety seventh Best Picture winner at the 2024 Academy Awards.

If there was ever a filmmaker who felt like the purveyor of what it feels like to live in distressing times, it’s Sean Baker. With a filmography of independent cuts that look into neglected, maligned communities across the United States, Baker has become the champion of the unheard, whether you look at persons of the world or the indie filmmakers who have been drowned out by streaming services, franchises, and entertainment-based monopolization. Baker is an auteur in what feels like the almost truest sense of the word, seeing as he not only directs, produces, and writes, but he also gets involved in other ways (for instance, he was nominated for an Academy Award for editing Anora, the very film he wound up winning Best Picture for). What Baker could achieve with just a simple iPhone and a tidal wave of imagination and purpose is unparalleled. He is a dreamer in the sense that he dreams for those who need the escape: life is a brutal test, and many of us are suffering as we try to best it.

After numerous successes, and years of adoration amidst the indie film community, Baker broke out into the big leagues with Anora: easily his highest-budgeted title to date (I am pleased that this director, one of whom could achieve so much with very little, didn’t squander this make-or-break moment when it fell in his lap). Once again, Baker doesn’t just dial into a small part of America’s culture and contemporaneous livelihood, but a specific community that rarely gets touched upon. This time, he places sex worker Anora — Ani — Mikheeva (who is Uzbek-American) amidst the comforts of the son of a Russian oligarch, who lives in a mega mansion in Brighton Beach, New York. Now that is focused. Ani (Mikey Madison in a breathtaking performance) has had a very troubled life, but we never get the full story via her memories; we do get enough information from her personality and inner strength. Ani has had a rough upbringing and works in a strip club to get by: a reality for many. Now, neither Anora or Baker are shaming sex work, but they are aware of how many people, mainly women, resort to it in order to survive. Ani isn’t looked down upon for her methods of employment, but her struggles are also understood and projected.

Anora is an unconventional Best Picture winner, much like Midnight Cowboy: an indication of distressing times via stylish, rebellious cinema.

Once Ani meets Vanya (Mark Eydelshteyn) at her workplace, they have many trysts together. At first, it feels like Vanya is just getting his fix again and again, but there does seem to be a genuine romance here. Vanya does nothing but play video games, smoke marijuana, drink, and have fun. His wealthy, esteemed parents resent him and his juvenile ways, so his time in New York is threatened once his residency status expires. During a Las Vegas getaway between Vanya and Ani, the former proposes; Ani says yes. Now, not only are they to be married and live happily forever, but Ani can give up her life of stripping and prostitution and live to her full potential, while Vanya can have a green card and remain in New York. Even outside of the romantic angle, this is a winning situation for both. However, this news spreads to Vanya’s family who demand an annulment; they send goons over to Vanya’s house to stop the wedding from happening, including the well-intentioned brute Igor (Yura Borisov). Anora turns from a whimsical, sex-filled fairy tale to a harrowing toppling of dominoes: a chain reaction of calamity.

Now, the upbringing of this twenty-first-century Romeo and Juliet couple is important. Ani had to act as her own guardian and tough out the real world mainly alone. Vanya has coasted and never had to stand up or work for anything. These differences will affect this engaged couple in crunch time. Meanwhile, Igor has some growth of his own to do. He blindly agrees to do whatever is asked of him, including some highly problematic requests — all to stop Ani and Vanya from tying the knot. I do love that Igor as a person shifts and becomes a bit more of an understanding, sympathetic individual who wants to find ways to protect Ani (however, if he crossed the point of no return is up to you to decide). Igor experiences the most change in Anora, which is interesting when you think about it because he felt destined to be a grunt without a spine and instead became one of the most interesting aspects of the entire film; perhaps he is symbolic of the growth even bad people are capable of should they open their eyes and finally see the bigger picture.

Anora is a fascinating character study of unfortunate souls who experience lives beyond their control.

Whether you look at Ani or one of the henchmen like Igor, Anora is spotlighting people whose lives are beyond their control; they could lose their livelihoods if they do not obey those paying them. However, Ani finds self empowerment in her work (which could easily break those who partake in it, but Ani is strong enough to persevere), whereas Igor and the other lackeys are clearly frigid and miserable; they are forever tasked with doing the deeds that the elite don’t want to dirty their hands with. Ani is in a position where she finally has a say as to what direction her life will take, and she won’t take no for an answer as Anora gets nerve-wracking, chaotic, and electrifying. While also a hilarious film, Anora is the kind of motion picture that feels like a rush because of how relentless it becomes. The film doesn’t let up until its final act of acceptance and exhausted grief: a farewell to what could have been, the revelation of true natures, and the fantasy world coming crashing down. Anora concludes with a haunting final image of the release of inner demons, a realization of what is to come, and a forsaken soul finally feeling some sort of authentic love, even if it’s from someone she doesn’t care for back.

The credits roll sans music, and just with the sound of windshield wipers swiping back and forth; you can only briefly clear away the mess before it comes back. Life can be a never-ending challenge for most people, no matter what your background or present are. I can’t pretend to know what Ani’s experience is like at all, but I do know how such an uphill battle feels. I think most of us do: when life cannot stop kicking you while you are down, especially when it tosses you false hope. A film like Anora — an independent, rebellious release — can only exist during a time period of extreme divide, suffering, and anxiety; if you look at Midnight Cowboy and its counterculture anarchy, you’ll find another like-minded film that the Academy Awards understood was a depiction of society’s frustration and concerns via taboo storytelling.

This is Anora’s time, and I cannot think of many times in the Academy’s history that such an unapologetic, courageous film resonated with the Oscars enough to win Best Picture (in what ways does Anora curtail itself to convention?). Anora joins rare company: it is only one of four Palme d’Or winners at Cannes Film Festival to win Best Picture at the Oscars (alongside The Lost Weekend, Marty, and Parasite). I’ll never forget the press screening I attended at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2024: one where jaded and well-experienced cinephiles like myself were cheering and applauding throughout Anora as if it was our Star Wars; the pin-drop silence of the final sequence was even more deafening. No matter what the story is about or who is at the forefront, a skillful director and screenwriter can turn any topic into an affecting, unforgettable, impressionable experience. Such is the case with Sean Baker and his magnum opus Anora: an unorthodox — but highly deserved — Best Picture winner which accurately alludes to the era in which it was released. This film is impossible to ignore; this Best Picture statuette proves it. This goes out to all of the Anoras of the world: you are heard, understood, and loved for who you are.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.