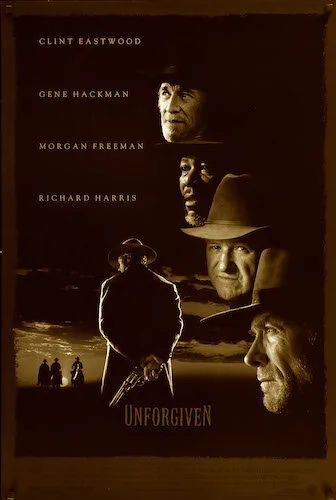

Unforgiven

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Unforgiven is the sixty fifth Best Picture winner at the 1992 Academy Awards.

It took decades for the Academy to even acknowledge another western for the Best Picture category, let alone award any film from the genre. In terms of actual wins, you’re looking at around sixty years between the atrocious Cimarron, and the fitting love letter to old timey westerns Dances With Wolves. As quickly as Kevin Costner was greeting the forgotten genre with open arms, Clint Eastwood was finally ready to say farewell to it for good. Costner was a major western fan. Eastwood lived the genre through and through. He surpassed the golden age, helped lead the spaghetti western trend, and now was spearheading the neo western movement. Costner was reminding a new audience of a beloved yesteryear. Eastwood grumpily begged for us to move on to greater things. By putting the final bullet in the genre for himself, Eastwood, perhaps accidentally, revitalized the genre better than any of his contemporaries (even Costner).

Unforgiven could only be directed by a western icon that was getting tired of the status. It tells the tale of a hired hand now living the life of a pig farmer, unable to escape his many demons. His nightmares come true when he is asked to kill one last time. A prostitute at a brothel in Big Whiskey, Wyoming, has been cut up beyond recognition, and abused beyond repair. Her fellow workers do not agree with the ruling placed on the two men that attacked her: a slap on the wrist, essentially. Therefore, the prostitutes band together to hire the farmer, Will Munny, to kill these two jerks. With the nobility attached to the job, and the difficulties he and his family currently face, Munny feels forced to accept this job.

The Munny farm; shot like a golden age western, to remind you of how the genre once was.

Like a vehicle actor, Eastwood understands the dependency that the genre’s finest heroes have had to get by. As a filmmaker, Eastwood could see greener pastures ahead, and he was going to do whatever he could to get there. Using the words of screenwriter David Webb Peoples, Eastwood places himself in the film, even on a literal level. He plays Munny: a gunslinger forced to look back for old times sake. Much of Unforgiven is done begrudgingly, but with a little ounce of love. Eastwood may have been growing tired of the genre, but he never forget why he loved taking part in it in the first place. Unforgiven is not a '“good riddance” rant, but a "promise to never forget the ride that was had. No matter how dark Unforgiven gets, it’s only to make the separation final. It all comes from a place of love.

Boy, does Unforgiven get dark. Even conceptually, you’re looking at elderly friends agreeing to revert back to their old ways, for a decent pay, a strong cause, and the final bout they can call the last rodeo. Munny finds his best bud Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman), and this daunting task no longer seems quite as bad. Munny still wants to just get it over with. The whippersnapper they are with named the “Schofield Kid” is an arrogant youth that claims to be more daring than the vets, whose company he keeps. At the end of the day, this “Schofield” chap (Jaimz Woolvett) is nothing more than a scared child thinking he was signing up for something redeeming. The common silence found in his elders tells a different story. You never forget any of your kills. No amount of whiskey can erase any of these instances.

Munny and Logan, riding together.

Back in Big Whiskey, “Little” Bill Daggett, the sheriff of the town, is painted out to be an unreasonable authoritative figure; the villain of the picture, if you will. Daggett (Gene Hackman) is constantly trying to set examples of the ill-willed in this neighbourhood, even if it means losing his own dignity. After the verdict of the assaulted prostitute Delilah, he carries on about his own way; doing a poor job with carpentry, maybe as a symbol of how close to breaking Big Whiskey actually is. The big hotshot English Bob (Richard Harris) is arriving, and this is Daggett’s ticket to really proving his power in the town. Bob is reduced to nothing in Big Whiskey, and in the film: the works of legends mean nothing to a sheriff trying to run the show.

What I found baffling — in the best way possible — the first time I saw Unforgiven as a curious teenager, is how easily we are led into hating Daggett. That’s exactly what Eastwood wants. We’re used to the cookie cutter villain, especially in the western genre. In a world full of gun toting hooligans, audiences are used to being told who to follow. How can this murderer be better than this one? Through obvious ethics, and specific filmmaking tropes? By all means! However, this was Eastwood’s send off, and he wanted it to count. That’s why anyone visiting Unforgiven for the first time is destined into being duped.

Sheriff Daggett is easy to dislike, but most of his decisions come from his best efforts in protecting his town.

Of course Daggett seems like the main guy to hate. He forbids anyone else from bringing a gun into Big Whiskey, although he himself can carry one. He gets in the way of the mission to help avenge Delilah. He must be the worst guy here. The closer to Big Whiskey that Munny and company get, the closer to a good old fashioned western romp that we are. We eventually reach that point, and it’s conflicted. Logan cannot bring himself to being the ruthless killer he once was, and the Schofield Kid has no idea as to what he signed up for. The only one that is able to carry out the mission without as much trouble is Munny, who is now resorting back to his alcoholic ways. It’s far too late. We’re already in Big Whiskey. We can’t leave now.

With the Schofield Kid forever damaged, and Logan being turned into a cautionary tale for the town of Big Whiskey, Munny is now drowning in his sorrows. He gets a glimpse of how Delilah is truly doing after being taken care of by her and the other prostitutes, and that’s the final straw. If he’s going to go back to hell, he’s going to become the devil himself. The final scenes of Unforgiven are the absolute form of changes-of-heart committed to screen. Munny becomes the villain, and Daggett is now the misunderstood hero of the town, facing the angel of death. With dark shadows, booming thunder, and complete bloodshed, we are startled, knowing we have been rooting for the most dangerous person in the film. It’s the supreme bait-and-switch.

Munny transforms from hero to villain, or, at the very least, antihero

Unforgiven shattered the conventions of westerns in the same way that Chinatown decimated films noir. The latter ushered in the neo noir movement, and so it was only appropriate that Unforgiven marked the official start of the neo western. If we don’t include No Country for Old Men (which, to me, is a western, but not to all), then Unforgiven is undisputedly the greatest western to ever win Best Picture. It’s ironic, because it carries two conflicting identities. It is the last bullet in the old genre out back, but it is completely responsible for the differing ways of modern westerns. The genre is very much alive and well, too. We even have a True Grit remake which is better than the original.

Dances with Wolves was great as a form of nostalgia, but Unforgiven was essential in the demand of audiences across the world. Westerns could forever remain, but we have to stop the tired stories we’ve heard a thousand times. With a modern perspective of an old era, by a master that knew exactly how he wanted to bid adieu, Unforgiven is a morality tale that mocks the former barricades of the very genre it is professing its love to. There was no turning back, whether it be Clint Eastwood progressing as a well-versed cinematic icon, or a genre that couldn’t be left for dead.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.