Distance Learning Film: Camera Shots

The way a subject or setting is shot is extremely important. It may seem silly to do this much work while watching a film, but it’s important to know why each and every image is set up the way that it is. What does a shot say about what is on screen from a narrative standpoint? Yesterday, I looked at the use of the rule of thirds, which is as bare-basics as photography can get. Now that we have that in our minds, we’re going to look at the other important aspects of a shot: the ways a camera is angled, what position a shot is taken from, and more. Today, we need to go over the actual shots themselves, as we can’t discuss the flourishes a shot can be accentuated with without knowing what shots actually are. In its barest form, a shot is exactly what it sounds like: what is captured on screen at any given moment.

It isn’t redundant to analyze what you are seeing at all times while watching a film, because film was a visual medium from the very start (even before it became a sound medium as well). Over one hundred years have gone into the development of the visual storytelling element of cinema. Therefore, you can guarantee that what you are seeing isn’t arbitrary by any stretch. The type of shots a scene or sequence is held together by is very important, because so much can be told by the specific combination of shots these moments can have. If a scene starts with a household, then cuts to an elderly man staring out of his window at a reasonable range, we immediately learn where we are and whose story we are currently listening to. Had we not gone in close enough to see the man, we may have not paid him any mind, which would disrupt the story. What if we zoomed into the chimney of the house instead of the man? We’d be thwarted by the time his story comes into play the next scene.

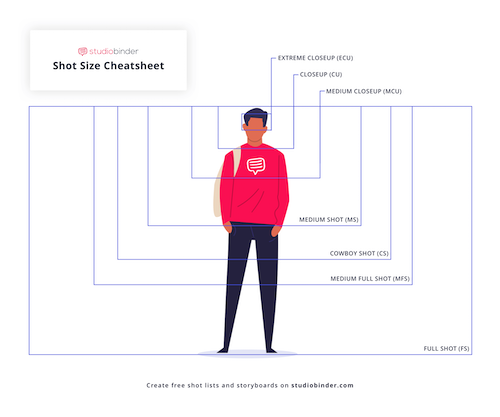

Doing research for this lesson, I stumbled across a guide that is — in my opinion — absolutely perfect for all types of shots, and I will be promoting it on each of these lessons. StudioBinder is a management software for visual media like film, television, photography and more. They also host their own how-to programs on understanding different techniques in these avenues. Their thorough guide on camera shots of every sort was released in March of this year, and I don’t think I could have done a better job at providing such a precise, quick look at every example. That can be found here. The guide also comes with this cheat-sheet on every type of camera shot in one picture; it’s incredibly convenient.

Courtesy of StudioBinder.

What this lesson will focus on is opportune times to use each shot, with examples of each.

Extreme Wide Shot

There Will Be Blood

Perhaps the most certain type of shot is the extreme wide shot: the furthest pulled away from any type of focal point. This is best used for setting up a scenic view, to establish a setting, create an emptiness, capture a large scale event (like the above image) and more. A film can’t be told exclusively through this type of shot, unless it’s a photographical documentary of some sort. There is too much distance for a view to get acquainted with anything personal here, outside of what we make of our own observations of the settings presented.

Let’s take the opening to No Country for Old Men, which is a very existential film. We have a narration to get a second story told while we watch empty landscapes, but what we see is already its own initial tale. We see the film takes place in the southern United States, in presumably a lowly populated area. Not much happens here, which makes us beg the question: why are we now here? What’s going to shake this town up? By the time the film cuts to any form of a subject, we already know as much as we need to know about their surroundings. This is a nihilistic wasteland, and we’re in for a slow burn, unfriendly ride.

Wide Shot

The New World

Closer than an extreme wide shot, this type of shot usually has a focus on a subject to some degree; yet, the setting around them still feels gigantic. In some cases, this can be used to further the isolation that extreme wide shots can instil. However, these can be used as establishing shots to allow a subject’s relation to their surroundings to be seen. The above image shows someone wading in the water: a trust of one’s environment, and a necessity that can be fulfilled here. An entire film shot in this style would still feel rather uncomfortable, because you aren’t really getting as familiar with the characters as you are with their worlds. Still, starting a scene off this way — or tossing a shot of this nature in a sequence — can add to the bigger picture, if you spend the rest of the scene within the character’s personal bubble especially.

In the following clip from The Piano, you can see the tail end of the previous scene left in. Lucky for us, we can fully understand how the next scene is then introduced: with a wide shot of the beach, and the characters running on it. A mother marches over to the piano she hasn’t been able to play until now, and her daughter sprints to catch up to her enthusiastic mom. The man that brought them to this beach slowly follows behind, as he doesn’t necessarily care about this mission. You can see the piano left isolated on this beach, without a soul in sight to hear it or play it. This thus becomes a haven for a musician mother and her beloved daughter during a move to a new land which has been hell until this point.

Full Shot

All About My Mother

Here, the focal point takes up a good portion of the shot. It is full, because you can see the full human body, and it is around the length of the shot itself. This is where people (or other subjects) and settings meet together as one, as if the image has flattened. No longer does the backdrop suffocate or comfort an individual. If anything, the person begins to smother their surroundings. Having an entire film made up of these shots would feel too static, and you may feel the need to zoom in or out even just the slightest bit. Full shots are good at establishing size ratios, personable relations with a subject’s whereabouts, and a lack of distance from the goings-on within a scene; that void of any sort is now gone.

Below is a dance number from An American in Paris which mostly takes place in a full shot range. Like I said before, having an entire scene or film shot this way would feel uncomfortable, so notice how the clip eases into closer shots of the dancing pair, before zooming back out again. It’s as if you have taken part in this dance and are waltzing with the characters. You get a taste of what’s around them without ever going too far and losing your connection with them.

Medium Wide Shot

Taxi Driver

From here on out, the subjects on screen are going to dominate the shot, and the setting takes a bit of a backseat; you can see why establishing shots are absolutely necessary now, otherwise we may not have a great idea of where these characters are at any given time. These aren’t full shots where an entire body is shown, but enough distance is left so you’re not completely within the personal spaces of the characters on screen, and you can still see most of their movement. If a scene requires both distance and closeness, then a medium wide shot is wise to use. Consider it a literal mixture of the medium shot — which frames a subject’s torso and head areas — and a wide shot: the establishment of a scene’s surroundings. We feel like an onlooker, rather than a part of the conversation completely.

In the below Roman Holiday clip, our subjects run to a statue and are contained in a medium wide shot. Whenever the film cuts to a closer shot, you feel either more tempted by the lore of the statue being discussed, or familiar with how each character is feeling. When you cut back to the medium wide shot, you are placed back in your safe perch, granted the ability to not have to stick your own hand in the statue’s mouth.

Medium Shot

Paths of Glory

I consider the medium shot to be the most personal, because you feel as though you are at arms length with a subject. You can hug them. You can fight them. You can hear them: their voice hits you directly. We’re no longer at any form of distance away from these characters, so there’s no dodging what is going on. You’re not threatened at this distance in a physical sense, either: characters aren’t right up in front of you and causing a discomfort. A majority of shots are taken at this distance, because it’s a great anchor point to return to. You set an establishing wide shot, then return here for some story. You cause a sensation with an extreme close up, then retreat to a medium shot to establish the proper personal environment of a scene. Out of all of the shots that are possible, an entire film made up of medium shots — while boring — would likely feel the most normal, because you feel as though you are at a conversational distance: across a table, for instance.

In this Moonlight clip, a man is teaching a child how to swim. To ensure you that the kid is going to be safe in both the hands of this guardian and the body of water he is swimming in, the sequence mostly consists of medium shots: a comfortable place that causes neither tension or looming dread. This is a moment of solace in a dramatic coming-of-age tale, hence why it is a considerable highlight of the film.

Medium Close Up

In the Mood for Love

Now, things are getting even more personal. Slightly closer than a medium shot, these types of shots can be reserved for more intimate encounters: private conversations, romantic embraces, or even negative relationships (people fighting and standing their ground). Setting at this point is as lowly prominent as it can be; the final two types of shots feature characters that take up the entire space of what we see. So, medium close shots have a similar effectiveness of a medium shot, only with a little less of a comfortable distance.

In this Blue Velvet scene, a scheme is being plotted. We start the shot at a distance, so we can see what type of diner these two teenagers are conversing in. From there on in, we’re a part of this secret discussion. The conversation is a bit more hushed than room volume — as to not be heard — and we’re as close to the table as possible. We sense a bit of dread, because we can see that no one else is supposed to hear this.

Close Up

Summer with Monika

Now, we are completely in the personal space of a subject. Either that, or we have zoomed into a piece of a setting closely enough to examine it at a micro level. A close up is when a subject dominates an entire shot at a clear level: you can easily tell what it is. We can read a lot from close ups: moods on someone’s face, the chemistry between multiple parties, a whisper meant for only us (or a receiving character), and more. If an object is being featured, there’s clear importance as to why it is being shown; maybe it belongs to a character and is important to their story, or it’s got a specific piece of information that’s valuable exposition. This is cinema’s form of a magnifying glass, and close ups are frequently used to establish more immediate events than a wide shot would. Instead of showing just a vast landscape, we’re seeing personable traits to a location: maybe refrigerator magnets set up by a creative character, or post-it notes indicating either a frantic or a headstrong character (depending on what these notes say, and how they’re laid out).

In this scene from Requiem for a Dream (a film littered with close ups and extreme close ups), we know we’re a part of an intimate moment because the furthest we pull away is to a close up position. We almost feel invasive, peering in on this romantic moment between two lovers, as they take this opportunity to just stare at one another and confess their feelings. All we see otherwise are extreme close ups, where the human body becomes the setting (ears, stomachs, arms).

Extreme Close Up

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

We’re as close as we can get now. We’re no longer even looking at people as people. We’re analyzing particular body parts and their relation to their hosts: the above image from The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly indicates shifting, uncertain eyes. You’ll be lucky if you even get an ounce of setting at this point. Objects zoomed in this closely will be magnified in their own right, not in relation to the setting by any means. So, you’re looking at the insides of a flower, the mouth of an animal, the eraser of a pencil, or the seeds of a strawberry. That’s how close we’re talking. An entire film shot like this would be an absolute headache, but having these kinds of shots tossed in creates an intense sensation of any sort. Shots this close cause agitation or spectacle. Any establishment done here is on a micro level, perhaps for abstract or thought provoking reasoning.

The opening to Citizen Kane is full of extreme close ups, the first being the “No Trespassing” sign to start things off. We don’t get where we are yet, but we know there’s a powerful force here. This cuts to an extreme wide shot of a mansion and its lot that looms over us: we now understand the power established earlier, and can apply it to a specific property. Once we get to the subject on his deathbed holding onto a snow globe and uttering that iconic word (“Rosebud”), we have two more extreme close ups. We know more about this object that’s important to the subject than the subject itself. All we see are lips, and we can see what they say and how they say them. That’s it. A vagueness surrounds the character, and their connection to this object and the setting we see. These are fragments that Citizen Kane as a film vows to stitch back together. Thus, rewatching this opening after viewing the whole film gives more prominence to each item we see: who Charles Foster Kane was as a person to the people, to himself, and to those close to him. A mystery the first watch through, and a collection of personal traits the second.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.